[I]s the coffee industry ready to go down the specialty milk rabbit hole? It’s a little ironic that we sit through coffee training, hover over cupping tables, listen to the importance of certification talks, and yet rarely do we delve into the standards, grading, pricing structures, regulations, supply chains, and processing practices of milk. We’re talking about an ingredient that in espresso drinks makes up two thirds or more of the crazy goodness that’s going on in our cup. We have come a long way when it comes to understanding the importance of details pertaining to quality in coffee, its growing regions, the needs of coffee farmers, and the development of transparency and growth across all channels of the supply chain. What if the attention given to coffee was also as laser focused on milk? What if we knew as much about the cow-to-cup process occurring in our own backyards?

Four years back, I sat in an SCAA Symposium (now Re:co) planning meeting. Compelled by conviction and enough information to start a conversation, I submitted a short syllabus for my vision to tell an up-close-and-personal story of dairy in regards to coffee. It sparked something in the room and the consensus was this topic needed some serious storytelling.

The research portion of my preparation changed my life. The more I learned the more I realized, painfully, I am part of a problem, one in which I choose milk without completing anything like the due diligence I bring to my coffee curation. Here on our own soil were small dairy farmers producing the best milk I had ever tasted in my life. Some of the farms were less than two hours from my home. It was one of those slap-in-the-face moments that you really can’t hide from. Back to square one, it was time for research and discovery.

Think about the first time you participated in a coffee cupping. An educator is sharing geography, elevation, farming challenges, the type of processing, and in the back of your mind you are tasting all this. It’s the moment when coffee touches you on multiple sensory levels. I remember thinking, “I can never waste another coffeeseed, there’s too much effort on the seed to cup process for me to just let one single seed fall to the ground.” I knew visits to dairy country would help me become more thoughtful and make better decisions. It did.

What comes after discovery is most often sharing. I am not alone in my milk curiosities. Along with my friends from La Marzocco and Pete’s Milk Delivery, I’ve been coordinating small field trips around the Seattle area in an effort to continue learning and supporting local dairies whenever possible. We recently brought representatives from Canlis, Cherry Street Coffee House, Caffe Ladro, and Stumptown Coffee Roasters to the northern border town of Lynden, Washington, to visit two small dairy farms: Twin Brook Creamery and Grace Harbor Farms.

Prior to our visit, I had seen a few small-farm milking parlors consisting of less than twenty milking stalls and the large outfits with the ability to milk hundreds of cows in carousel-style rotation. Larry and Debbie Stap of Twin Brook Creamery used to have one of those small milking parlors. This past summer they installed mechanical milking machines, a particularly special innovation for their small farm.

Upon arrival we toured the farm, learning about feed and types of dried grass, the cows’ living quarters, the Jersey cow breed, and the old way they used to milk cows. Then they took us to see the mechanical milkers, which not only allow them to milk cows automatically, but allow them to monitor the cows’ health. Dairy farming is tedious, detail-oriented work. The day starts long before the sun rises and ends, for most farmers, well into the sunset. Viewing this entire process opened my eyes to the complexities of dairy production and the variables that go into making each dairy’s milk distinct.

Milk’s Makeup

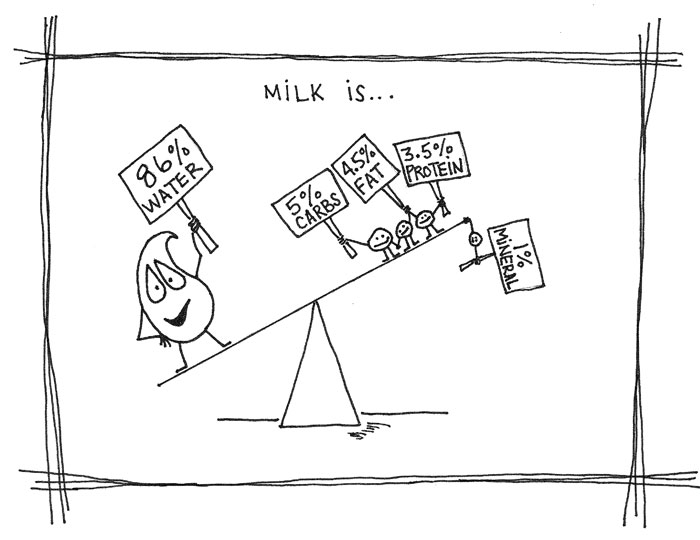

Milk’s components are actually quite simple, if we stay on the surface. Water makes up just around eighty-six percent of the liquid and 4.5–5 percent is carbohydrates made up of two sugars, galactose and glucose. When these two are brought together they create a compound molecule we know as lactose. Butter fat typically makes up 4–4.5 percent of the liquid. Another 3–3.5 percent is valuable proteins in the form of amino acids, wound up in little knots when cold. Various minerals make up the last one percent. Fat percentages can vary slightly due to the breed of cow and seasonal diet change.

From Farm to Carton

Cow-to-cup is hardly milk magic. A very time-sensitive process exists to safely deliver milk into cartons, jugs, or bottles. As soon as a cow is milked, the fresh milk is transferred to holding tanks and immediately chilled to a safe temperature just below forty-five degrees Fahrenheit. Then it goes to its next phase, the milk processing facility. There are three types of these:

Dairy Processor Cooperatives (co-ops), nicknamed the un-corporations, are farmer-owned processing facilities. This business model promotes regional farming while encouraging fair wages and fair returns, and can aid in keeping farmers farming. Co-ops sell direct or to distributors.

Dairy Processors purchase milk from multiple farms both regionally and nationally, depending on their goals. Milk arrives by semi-truck and is moved through production to boxes or jugs to sell direct or to distributors.

Farmer Producers are a cow-to-bottling all-in-one service. Not only do they raise and keep their own herds, they do all of their own in-house processing, pasteurization, fat separation, homogenization, bottling, and sometimes even delivery.

Standards and Processing

Whether that holding tank is right on the farm or milk is pumped into trucks to leave the farm, the next step is pasteurization. This process was developed in 1864 by Louis Pasteur and was originally intended to improve the shelf life of wine. It turned out to be a great solution to killing harmful bacteria sometimes found in milk. To date, milk is one of the safest liquids to consume in the United States due to high standards and government safety regulations.

For the most part, milk pasteurization is done in three different styles:

Ultra High Temperature (UHT), a process also known as sterilization using pressurized steam forced over milk at a temperature of 275 degrees Fahrenheit for two seconds. When combined with very sterile bottling techniques, UHT greatly extends milk’s shelf life, giving it two months or more from it’s bottling date. UHT-processed milk is most typically found in convenience stores where long “good until” dates are desired. This type of processing is also necessary when milk is traveling long distances for eventual sale and consumption in regions that do not farm. While taste is a very subjective topic, in comparison to the other types of processing, UHT processed milk can taste flat or stale, less sweet and caramelly depending on the milk quality.

High Temperature Short Time (HTST), processes the milk at temperatures around 161 degrees for up to fifteen seconds. This gives milk twenty-one days from the bottling date. This is the process most coffee shops use in the United States. When milk sourcing standards are high this milk tastes like milk, which is great! It is typically clean, sweet, and creamy.

Vat or Batch Pasteurization, which heats milk to 145 degrees for thirty minutes. This process has a reputation for leaving milk enzymes, natural nutrients, and good bacteria in the milk while eliminating bad bacteria. Due to the nature of this pasteurization process, milk dates range from fourteen to twenty-one days from bottling. Optimum temperatures for transportation and storage once purchased or delivered are also key. Vat-pasteurized milk really showcases the true flavors of milk, forefronting its creaminess and sweetness, and at times you can taste the feed or minerality in the cow’s diet. I’ve also noticed seasonal changes in flavor due to diet change, whether the cows are eating fresh spring grass full of seeds or winter hay from the summer harvest.

So is the advice to get out there and find the best vat-pasteurized milk you can? It may simply not be an option. There are a few good reasons for differing levels of pasteurization, I’ll touch on one very big one. Two-hundred years ago America was just turning thirty-nine and ninety percent of the population owned farms, producing their own food and dairy. Fast-forward to today, it’s safe to state just around two percent of the population produces the fruits, vegetables, grains, and dairy for the rest of us. For some regions, dairying locally is not an option, or the amount of dairy produced in a region simply does not meet demand, driving the need to ship in milk. Dairy, even after proper processing, is still a living product and vat-processed milk is most at risk of failing in its journey. Extending the shelf life can be beneficial to bringing a safe (and affordable) product to kitchens out of the reach of “local” milk.

Separation

Next up in the process is fat separation through a process called centrifugal separation. Using plates and a very fast spin cycle milk and fats are spun apart. It can be done cold or with heat. The second most valuable component in milk besides the protein is butter fat. If all milk was left with its full fat content there would be no cream or butter available in the market.

Homogenization

Now the homogenization process reduces the size of the fat globules by pushing them through much smaller holes, making the entire liquid more uniform in texture from the first glass to the last drop. Non-homogenized milk has not undergone this step, so the butter fats, which are less dense than the rest of the milk, float to the top. Baristas who use this type of milk will need to become the homogenizer, shaking the milk before pouring it in order to incorporate the fats.

From the usage standpoint stretching nonhomogenized milk for a cappuccino or latte is a little different as the fat is naturally, not uniformly, spread throughout the pitcher. Milk fats can also be above government standards for whole milk which usually means special consideration when stretching the milk for velvety micro-foam.

Standardization

Now it’s time to put the fat back in at measured amounts through milk standardization. Milk’s composition is adjusted to meet government regulated standards. Unless the milk is intended to be nonfat, fat levels of one, two, or 3.25 to 3.5 percent for whole milk (depending on the state regulation practices) are placed back in the milk.

Packaging

Whether boxed, bottled, or filled into jugs and capped or sealed, the newly processed milk is prepared for its journey to grocery store shelves, restaurants, and cafés.

In the Café

So how do we go from a cold whitish liquid to a comforting and decadent companion to espresso? What does steaming do to milk?

Anyone can blow up foam with a little heat but not all foams are created equal. In the coffee scene we typically use pressurized steam forced through a wand to heat and expand the milk (see the In House column on page twenty-eight for an explanation of the process). With a little control and purpose the introduction of steam warms the milk, unfolding those tightly bound amino acids.

Petrified of water, the hydrophobic end of the amino acid looks for the nearest fat globule or air bubble to jump into. Meanwhile, the hydrophilic, water-loving end searches out the nearest water molecule. This stretches out the protein, as if they were tied with a bungee cord but running different directions, and they rope and wrangle fats, air, and water into small herds. All this excitement is expanding the herd of microbubbles. When heated the butterfat softens, is thinned, and blends in. Maximized sweetness caps right around 140 degrees Fahrenheit. At this point sugars have broken out of their lactose compound, freeing galactose and glucose to be their simplified selves, amplifying sweetness. Bring it all home by folding that luxurious microfoam into your perfectly prepared espresso and voila!

Nonfat, one- and two-percent, and whole milk will perform the task described above, but not all milks are the same, as they each offer varying amounts of mouth feel due to the amount of butter fats. Regardless of the fat content, the compound sugar in milk called lactose will go through some serious change as it’s heated. Temperatures exceeding 150 degrees or higher will begin to burn or scald the sugars. When steaming, and depending on the fat content and whether the milk is homogenized or non-homogenized, our techniques vary slightly to achieve the results we are all looking for, silky microfoam for optimum texture and latte art.

Closing Thought

Are we indeed ready to have a solid look at major details around our dairy programs? Is it time to open up communication and transparency between dairy and specialty coffee? Given that the barista community is made up of some of the kindest, knowledgeable, and curious daytime bartenders of all time, I believe it’s definitely worth a shot.

—Sarah Dooley and Mary Benson are owners of Milk & Coffee Co.