[J]ames Hoffmann’s new book, The World Atlas of Coffee, which is his first, takes ambitious as its starting point and then shoots for exhaustive. It doesn’t hit that crazy a level of detail, which is lucky for us because it remains at once packed and approachable. Just one example: in the section on Burundi, Hoffmann details fourteen growing regions. It’s a book coffee professionals and enthusiasts alike should not just add to their libraries but dog-ear and highlight.

Opening with the history, production, retail, and brewing of coffee, Hoffmann spends more than a hundred pages at origin, giving special attention to traceability. Designed with gorgeous photography and an eye to draw readers through the sometimes bewildering process of brewing a simple cup of coffee, The World Atlas of Coffee is a book you’ll spend as much time looking at as reading.

We caught up with Hoffmann, who founded London’s Square Mile Coffee Roasters, as he bounced from London to Moscow to Seoul to Athens.

Q: What made you want to write this book?

James Hoffmann: The primary driver is actually wanting to own it and be able to use it. For as long as I’ve been in coffee I’ve wanted a book that I can use to reference information about origin, to look up various details about a coffee I might be tasting, roasting, or potentially buying.

Q: You’ve created a great blog, Jimseven, which just turned ten, that aims straight at the coffee industry. What made you want to write a book aimed at coffee drinkers?

JH: There are more and more people who are just a little bit interested in coffee. They’re buying better coffee, brewing it better at home, spending more on it in coffee bars. However, I don’t think specialty coffee’s growth has come with a great deal of clarity. I think coffee is now more confusing than ever. I wanted to write something that might help remedy that.

Q: What’s in here for the coffee professional?

JH: Lots too I hope! I think having a single point of reference for information on coffee producing countries—be it harvest times, altitudes, varieties, or even locations, is a great resource.

Q: On your blog you said that during every origin chapter’s research phase, you got to the point where the Europeans were jerks. How has that changed your understanding about coffee?

JH: I came into coffee at a time of great positivity (about ten years ago), where Fair Trade and other certifications seemed less important because we were pushing boundaries of pricing and changing our trading models. This meant I didn’t have much understanding of the unfair and abusive history of coffee in most producing countries. Writing histories for them really highlighted the need for change that we really still have. We dismissed Fair Trade (as a specialty focused movement) because it didn’t meet our requirements for quality. However, we never really looked at what it did achieve and how we might be able to build on it to improve it.

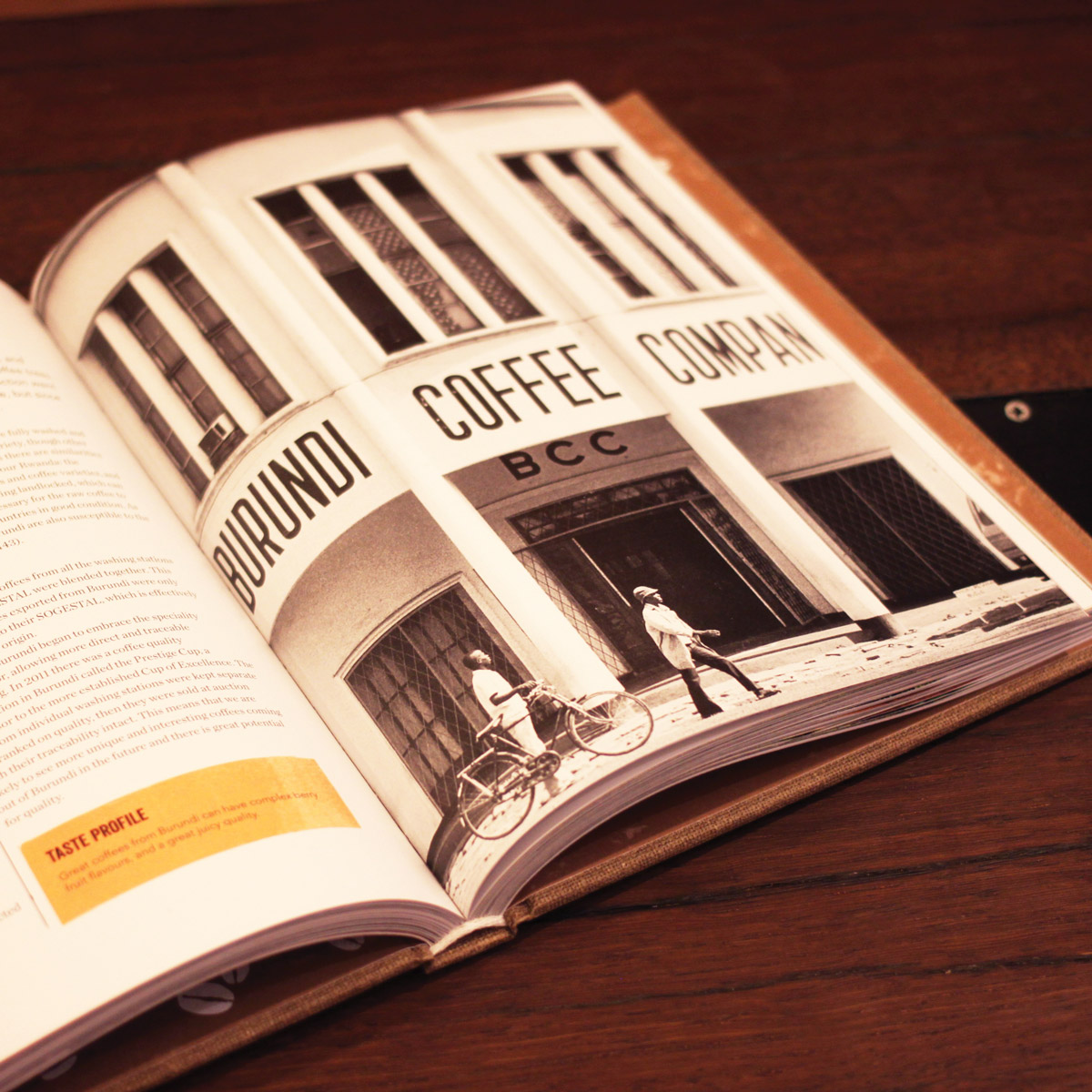

Q: Your sections about origin countries focus on traceability. Why?

JH: I think traceability is a key tenet of specialty coffee. I think it is how coffee people see coffees—we talk about where a coffee is from and who grew it, as the defining information of a product we sell. However, the “rules” for traceability vary country to country. As a consumer I think knowing what is possible for traceability in any country (and ideally why) is helpful when you’re buying and looking for the best and most traceable product.

—Cory Eldridge is Fresh Cup’s editor.