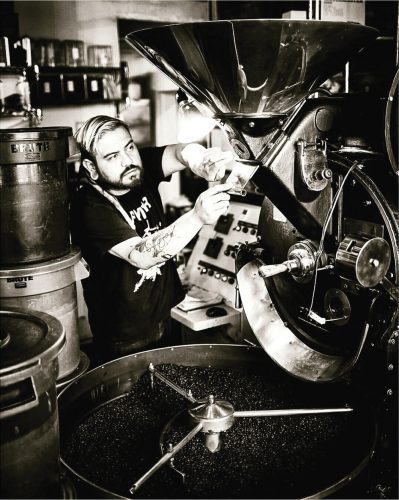

33 years old

Head Roaster

Black Oak Coffee Roasters

Ukiah, California

About 100 miles north of San Francisco is the unlikely coffee Mecca of Ukiah, California (population 15,882). The county seat and largest city of Mendocino County, Ukiah is surrounded by scenic Redwood forests, coastal byways, and world-class wineries. But in coffee circles, Ukiah is on the map for being home to one of 2017’s breakout cafés, Black Oak Coffee Roasters.

Since opening in 2012, Black Oak has earned local accolades for its small-town take on the hip, big-city coffee shop. In 2017 its renown spread internationally, thanks to the winning performances of head roaster Steve Cuevas in big-league contests including America’s Best Espresso, Golden Bean Coffee Roasters Competition and World Tasters Cup Championships.

“I was proud to win these awards. [They were] the start of people knowing where Ukiah was,” Cuevas says. “It’s the whole reason why I joined them, because they were roasting really great coffee when I first tasted them. I thought it was a shame nobody knew about them.”

Cuevas has worked in specialty coffee for 13 years. He started as a barista in the Bay Area, then made the transition to roaster after joining Black Oak in 2014. While a big-city guy at heart, Cuevas has a humble, laid-back attitude that fits right in with Ukiah’s country clientele.

“One of my favorite sayings when people ask how I’m doing is, ‘I’m alive. I woke up, that’s good enough for me!’ I feel really blessed for everything I have,” Cuevas says. “I have a great family, my parents are still together, my sister is doing good. I’m content living and moving forward.”

Fresh Cup: Where are you at on the scale of light to dark roast?

Steve Cuevas: Our biggest sales are our medium-dark roasts and our French roast. Those two coffees are helping us push who we are, helping us get collateral and grow bigger and bigger. We’re getting more wholesales based on those coffees. This helps our company grow. That money can help our side projects, our single origins.

FC: What is a typical day for you?

SC: We start by doing our cupping. Today we had about 18 samples to see if we wanted to buy. We spend about an hour or two on our cuppings, so we don’t get distracted or too carried away. After that I spend the rest of the day roasting until about 2 or 3 p.m., depending on how many roasts we have. After that we wind down, wipe up the machines, clean up the floor space, restock our coffee. Next, I start moving coffee bags, loading them up on carts and wheeling them into our roasting room.

FC: What makes a good day?

SC: A good day is when you come in and things are in order. Some of our coffees are already loaded from the previous day, so you already have something to work with. You have about an hour before the roaster is warmed up, so during that hour I start sorting through the coffees, making sure they’re all in the roasting room and ready to go. Hopefully the environment is actually working with you. A lot of our lines that we did really good with were roasted on warmer days, so we didn’t need as much power to achieve some of the roasting. It was a nice atmosphere outside, anywhere from 80–90 degrees outside. It helps out with the roasting because it’s sucking the outside air that’s already warmed up.

FC: How many different coffees are you roasting right now?

SC: We have a couple different varieties of coffee. Some of them are medium-dark roast, medium to French roast. We roast a lot of those so they are almost automated. Toward the end of the day is when I lean toward my exciting coffees, those I really have to pay attention to—single origins. Right now, I think we’re up to six or seven different varieties of single origin.

FC: Why do you schedule your roasts that way?

SC: In the mornings, if I’m doing a French roast and the machine isn’t fully warmed up and it’s off by 30 seconds, that’s okay. But 30 seconds could make a big difference when I’m roasting a single origin. By the end of the day, after we’ve been roasting back to back, the machine is warmed up, you have better control, you don’t have to worry about whether you should go way hotter to break even. You have to understand that sometimes you have to push it a little harder in the morning than at the end of the day once it’s warmed up. Then you can pull back.

FC: What machine are you roasting on?

SC: We’re using a 1957 UG Probat for our production, and we’re using a 1950s Gothot three-barrel sample roaster. Those two are fun, German technology, cast iron. I love them.

FC: Do you prefer working on vintage equipment over new?

SC: I haven’t roasted on too many new machines. When I went to the Roasters Guild Retreat, I got to play around with a Loring, cast steel front versus different bodies. For me, it’s understanding the percentage of conduction versus convection. Really any machine, whether electrical or gas, it’s a variation of radiation, conduction, convection, and different rates. It’s more about understanding what in particular you roast with. I don’t think one is better than the other. It’s more a matter of getting used to one or the other.

The analogy I use is I used to drive an old 1950s Volkswagen Super Beetle. The gears on that, you really feel them. You have to throw it into gear. I’ve also driven a BMW with a gearbox that is so smooth you don’t even feel the changes. One is stronger, whereas the other almost feels automated. The old school is just kind of a little bit of style, and also it was there, so that’s what I learned on. I have grown particularly fond of it.

FC: What have you learned about roasting on these machines?

SC: When I started roasting we had one static size for all roasts. But now we roast three pounds, 18 pounds, up to 33 pounds, which is more than suggested or recommended. So, I’ve gotten really comfortable with the thresholds of what the machine can do. I’ve been able to push it in a variety of directions, and using other machines also expands my point of reference.

FC: So, is it the machine or the man that makes the roast?

SC: People think some machines produce cleaner cups, that this one gives more body, but roasting machines are just heat sources. You can end up doing the same thing with multiple machines, you just get there through a different path. If you don’t understand that all we’re really doing is controlling those three variations of conduction, radiation, and convection, you’re going to attribute it to the machine. In reality, it’s the heat source. I don’t think that the machine is as important as your knowledge of understanding the path. In reality, all the flavors can get changed by the cupping table. As much I as I love roasting, I give more credit to the cupping.

FC: How often do you cup?

SC: We cup two to three times per week. Most of the time we’re cupping about 20 samples, up to 40 samples in a day. In a week, I might be cupping 60 to more than a hundred samples.

FC: How do you deal with palate fatigue?

SC: What I’ve found out is if you do 20 single origins, all light roasts, acidic coffee, by the time you get to five or six, it’s all just blending together, you can hardly differentiate little subtle nuances. So, I like to vary our cupping table by seeing some light, medium, and occasionally dark roast coffees. Variation of roast degree levels can make all the difference in picking out nuances.

FC: When you’re tasting sample roasts, how do you decide which ones to bring on?

SC: When we’re selecting coffees, I used to say let’s cup them all, taste them, and we’ll agree or disagree. Now I’m more open. Minamihara, especially, has opened up my eyes that it’s not just the country of origin. I visited the Minamihara farm and it was amazing, it changed my view of the country. I don’t go thinking this is a blender country, or this is an 82-plus country. I know now there are pockets of coffee at a lot of different places, but you have to find it. It’s a scavenger hunt. Tasting the Minamihara farm showed me that it’s not the country, it’s the processing, the method they put into it that blew my mind. Their coffee was right up there with any Ethiopia I’ve tasted. Now when I think of producing countries, I don’t write a country off. I look at it open-minded. Minamihara didn’t know they had great coffee. They threw it on the table with all these other farms and everybody lit up when they tasted their coffee. When people asked them how they did it, they said they just discovered that they accidentally made great coffee.

FC: What’s the key to Black Oak’s success?

SC: We have a whole team. Besides myself, we have two other roasters. When you have one roaster, you have one point of reference, so now we have three points of reference. Some of our greatest achievements with roasting have been accidents. So, when you have three roasters, you have the ability of hitting the line completely on point, or they do something they shouldn’t have done but it works out for us. We’ve learned from it. That’s where we have the mentality of it’s the taste, and make adjustments from there, as opposed to trying to figure things out by data.

Sometimes one person goes a certain direction with their love of coffee and then the others talk him off the ledge. Or it’s the other way around, when the other people love a certain coffee and the other doesn’t see it. Then we’re able to help him understand.

In addition to our crew of roasters, our owners (Jon Frech and Keith Feigin) have amazing palates. It’s basically five palates on all our roasting. We’re doing things that are very subjective. We’re proud of our people and the time and effort we put into it.

FC: How is the coffee scene out here in the country different from the big city?

SC: Coming from San Francisco, sometimes I feel the roasters there are roasting for their friends. For us in particular, we’re roasting for our consumers. Our single origins are for ourselves. Sometimes we have four or five on hand. It’s a little side project for the company, but it keeps us entertained. Our consumers and understanding their palate, that’s the bigger goal for us.