[K]ombucha is a new, old drink. The fermented tea has long been touted for its health benefits and refreshing effervescence, and is also a popular new addition to the explosive ready-to-drink market—in spite of its flavor, which can take some getting used to. If critics of this increasingly popular, fizzy brew scoff at the drink’s purported anti-aging properties and acquired taste, even more enthusiasts bask in the glow of kombucha’s magical acclaim. This sweet yet tart offering has been labeled a miracle beverage, an ancient elixir, and a cure-all. Possibly born of spiritual tinkering, the tea’s first fermented cultures may have been fostered by monks in misty mountain temples. Or that’s all hokum. Nobody is sure. Kombucha’s fuzzy history allows all kinds of myth making for a drink whose creation—tea fermented by a colony of bacteria and yeast—is wondrous on its own.

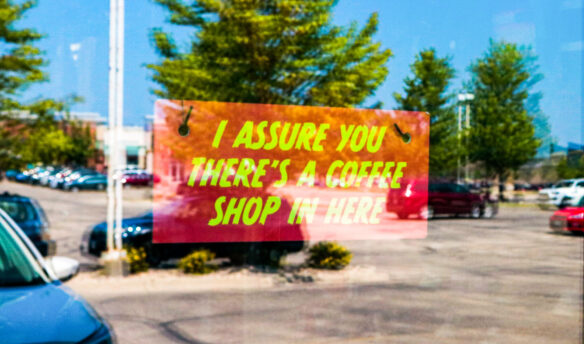

It may or may not be kombucha’s mystical nature that lends this drink such appeal, but history and health claims aside, there’s no denying the popularity of this unique beverage. While kombucha was once a home-brewed tonic sequestered to Russian kitchens and hippyfied co-ops, it is steadily becoming a mainstay in cafés looking to offer healthier options for patrons. Fizzy like soda, with vinegary tartness and a sweet tea base, kombucha stands in a category all its own that fits comfortably alongside quality coffee and carefully sourced tea.

Sitting on a sofa in one of his Tea Chai Té teahouses in Portland, Dominic Valdes, co-owner of Happy Mountain Kombucha, muses about the drink’s skyrocketing popularity. “There’s so much hot buzz and positivity over anything fermented,” he says. “Fermented foods, kimchi, even beer. Kombucha went from kitchens to something grand awfully quick.”

Valdes and his wife Angela are tea lovers who started brewing kombucha in 2005, when the drink began gaining steam in specialty tea shops. Under the umbrella of their wholesale tea brand Tea Chai Té, the couple’s kombucha program steadily grew and recently graduated to a larger, stand-alone production facility. Now Happy Mountain is available in restaurants, cafés, and high-end delicatessens, in addition to Tea Chai Té’s four locations. Valdes says while brewing kombucha presents challenges—“It’s a living product and there is going to be some variable in it”—the payoff is worth the added effort. Across town at Brew Dr. Kombucha, Matt Thomas has discovered much the same. “As soon as we were making it in the teahouses, we couldn’t make enough of it,” says the owner of Townshend’s Tea Company, a four-location company expanding its wholesale offerings beyond the Pacific Northwest.

Townshend’s first brewed kombucha in the basement of the company’s flagship teahouse, in Portland’s trendy Alberta Arts District. From low-key basement beginnings the program eventually grew into its own brand, Brew Dr., and the current production facility resembles a small-scale brewery, complete with a wall of fifteen-barrel brite tanks, a central bottling machine, and a row of shiny taps dispensing each of the company’s eight blends. A small team oversees the bottling, labeling, and packaging of the drink before it’s shipped across the country to coffeehouses, Whole Foods Markets, and other natural food stores. When asked about the ins and outs of brewing the drink of the hour, Thomas responds with a grin, “Well, that’s kind of an industry secret.” With the relative newness of large-scale kombucha production, brewers are still protecting the execution of their craft.

[T]he Manchurian mushroom, tea kvass, olinka: Kombucha has gone by many names, and its healing properties have been studied and celebrated throughout the world. The sixties and seventies saw a wave of new-age fads in America, many based on Asian traditions. Alongside acupuncture and yoga, kombucha fit the bill and first rose to prominence in the natural groceries and co-ops of the time, much like tea. Prior to its US introduction, kombucha was a popular home wellness remedy in East Asia. While its exact origins are hazy, few doubt its age—the first cultures go back almost as far as tea itself. From Asia the drink traveled to Russia and later Germany. Russian scientists studied kombucha extensively after World War II, investigating its potential as a cancer-fighting agent. (As he did most things, Joseph Stalin mistrusted the drink and eventually shut down research.) A number of German doctors pioneered its use as a treatment for inflammatory diseases and a host of other ailments.

Tea veteran Stephen Lee, co-founder of Stash Tea Company and Tazo, and the owner of Kombucha Wonder Drink, first tasted the fermented brew in the nineties in a colleague’s Saint Petersburg, Russia, home. Before returning to Oregon, the teamaker was given a kombucha starter, or SCOBY (symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast), to brew his first batch of the revered tonic.

“The woman who gave it to me told me she got her original culture from her great aunt in Siberia in 1939,” Lee says. “It gave me chills.” By placing the jelly-like SCOBY in a batch of brewed black tea back home, Lee transported the tradition and science of kombucha easily. He quickly fell in love with the tonic. In 2002, he launched Wonder Drink, one of the country’s more popular kombucha brands. Kombucha Revolution, a recipe book he co-wrote with author Ken Koopman, is slated for release this June. “Kombucha is a phenomenon,” Lee says. “Those of us in the category believe that it’s going to be a billion dollar category within a short period of time.”

When it comes to variables like pH and bacterial content, many companies will enlist microbiologists to ensure the purity of their formula prior to distribution. But from Lee’s story and other accounts, kombucha historically passed from hand-to-hand, brewed without fanfare through the simple combination of tea, sugar, and the culture. This homegrown aspect lends kombucha its wholesome identity.

[A]s kombucha steps out of the kitchen and into the limelight, drinkers are less concerned with kombucha’s legacy and more excited about what it does. Brands with names like Synergy, Revive, and Alchemy speak to the drink’s reputation as an uplifting “wellness” beverage in line with a health-conscious lifestyle. Consumers feel good about a drink often found at farmer’s markets and alongside other organic products.

Kombucha offers a refreshing, low-sugar option to knock back soda cravings. It also provides the benefit of probiotics (the “good” bacteria in the digestive system), energy-boosting B-vitamins, and usually a bit of caffeine. The result is an energizing brew that will certainly give you a lift. Bringing this drink into cafés and teahouses offers a bevy of rewards. Jill Makoutz, who co-owns Bradbury’s Coffee and Tea in Madison, Wisconsin, says she and her husband originally decided to serve kombucha because it fit with the shop’s seasonal and organic offerings. “We wanted folks to feel good about what they were purchasing from us, and more importantly, feel good about what they were putting in their bodies,” Makoutz says. Local brewer Nessalla Kombucha crafts its blends with seasonal ingredients, which pairs well with the shop’s farm-to-table values.

It’s fairly easy to add kombucha to your menu. You can stock a cold case with various flavors or invest in a kegerator behind the bar. Tapping small kegs of different flavors provides a green and profitable addition for locations low on cooler space. Kegs keep the drink fresher longer, the taps look cool, and the setup differentiates the tea from the rest of your offerings.

“We find that coffeehouses that add kegerators in addition to having a cooler in-house don’t just see the same sales spread to different products, they actually see increased sales,” says Thomas, referring to Brew Dr.’s five-gallon keg delivery program. The company’s northwest sales director, Griffin Johnson, handles more than 600 retail accounts. He says kegs are “better for us, since we spend less on packaging; it’s better for the business owner, because they get as much or more of a margin compared to bottles; it’s better for the customer, since they spend considerably less for the same amount of product.”

Part of the allure of kombucha is its versatility. It starts as a simple fermented tea, but when combined with spices, herbs, and fruits, flavor-savvy recipes spin this drink in fresh ways. Happy Mountain pairs mild teas like oolong and white peony with floral flavors like peach blossom and lavender, which Valdes says sets the brand apart. “We wanted to make something different so we use lighter teas, white teas, bao zhong. It’s just not as heavy,” he says. “It’s a light, fizzy, great introductory kombucha.” Brew Dr. Kombucha boosts their wellness edge with blends incorporating organic teas, detoxifying herbs, and energizing spices like cinnamon and cayenne. The market is flooded with brands offering interesting profiles, from standards like spicy ginger to genre-bending coffee kombucha. In the café, kombucha makes a great starter for refreshing iced beverages and even inventive cocktails in shops that serve alcohol.

All this explains why the brew is now a regular player in coffeehouses, teashops, restaurants, and yoga studios. Kombucha can even be found on tap in bars for teetotaling patrons and by the growler-full at grocery stores.

It seems as drink culture grows, whether its coffee, tea, beer, wine, or even juice, more and more space is created for new drinks. A decade ago, kombucha was an experiment you might come across in a friend’s closet. Now, still in its infancy as a consumer product, it’s become a mainstay.

—Regan Crisp is Fresh Cup’s associate editor.