I dreamt about matcha last night. I guess that’s not that crazy. I drink a lot of tea, and matcha is pretty dreamy. I was at a tea bar waiting for my drink, a matcha cortado, and the barista handed me something beautifully green and decadent. Six ounces or less of strong, umami-rich matcha topped with rich, green microfoam and topped again with forest-green whipped cream.

OK, so maybe it was a little crazy. But, in my subconscious café, it tasted amazing. But what is matcha, besides the tea fueling my dreams?

Let’s explore.

A Brief Background of Matcha

Matcha comes from Japan, primarily grown in the Kyoto and Aichi prefectures. Though you can find matcha from other countries and regions, they aren’t matcha in the true sense.

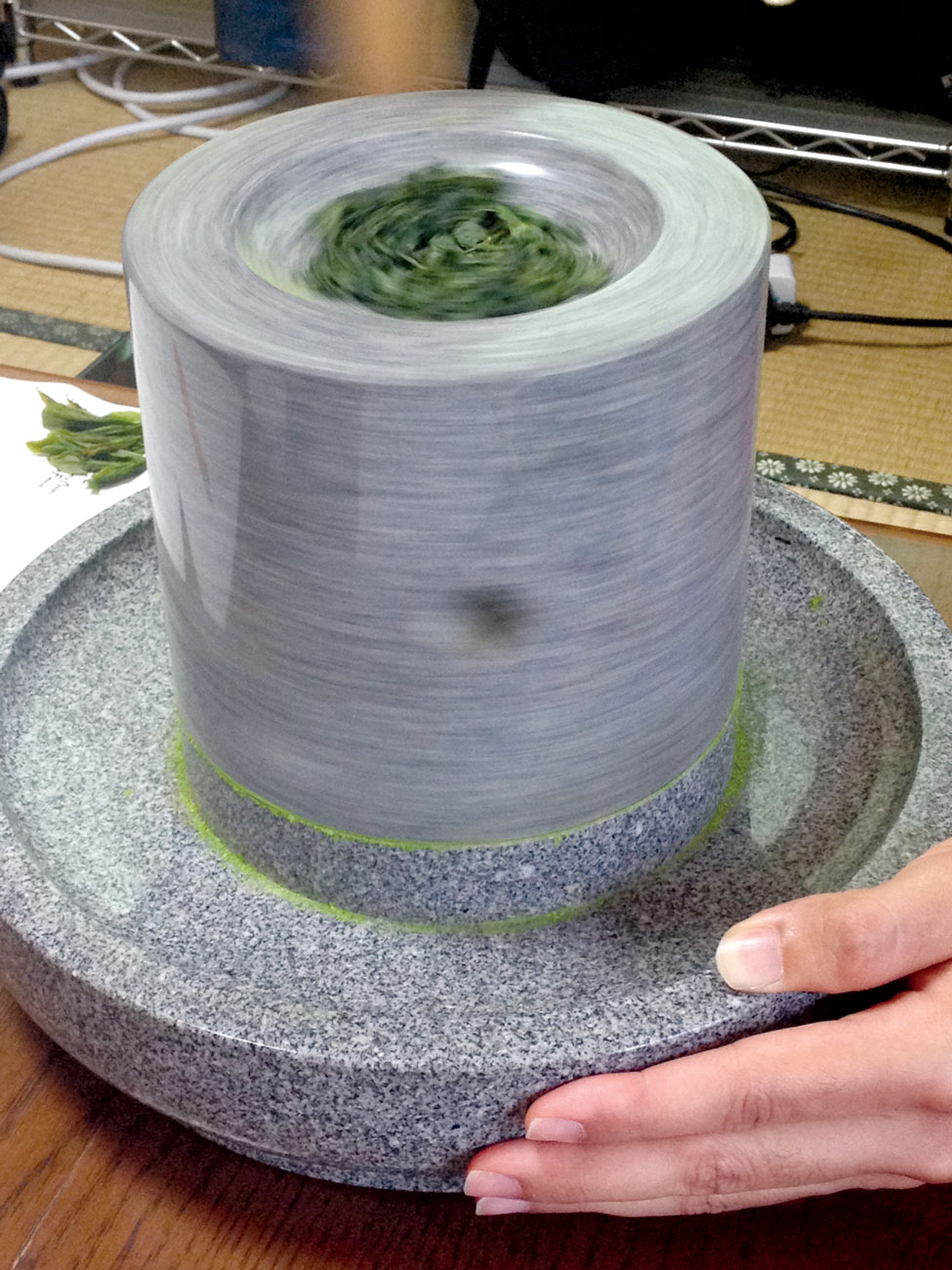

The process of making matcha has been finely tuned in Japan for centuries, and it requires more care and patience than almost any other tea. Leaves are shade-grown for up to a month before being exposed to sunlight, which lends them their bright color and concentrated nutrients. Leaves are plucked by hand, deveined and de-stemmed, lightly steamed, and dried, and the best parts of the leaf, called tencha, are sent to be stone-ground into matcha.

The process of making matcha has been finely tuned in Japan for centuries, and it requires more care and patience than almost any other tea. Leaves are shade-grown for up to a month before being exposed to sunlight, which lends them their bright color and concentrated nutrients. Leaves are plucked by hand, deveined and de-stemmed, lightly steamed, and dried, and the best parts of the leaf, called tencha, are sent to be stone-ground into matcha.

This last step is slow but crucial. Massive granite grinders are used to make matcha super-fine without heating the sensitive leaves. It takes a skilled artisan to craft a matcha grinder or repair one. Aiya America estimates that only ten Japanese artisans have the necessary skills.

That’s just a basic overview of how matcha is made. But matcha’s quality differs based on location, flavor, and consistency, dependent on processing, plants, the weather, and the care given by the farmer or producer.

The complexities of quality build fast. Ian Chun, CEO of Matcha Latte Media and tea merchant at Yunomi in Tokyo, says there are too many styles of matcha in Japan for most tea consumers to wrap their heads around. “One factory presented me with a price list for matcha with twenty levels of quality,” he says. “It’s too complicated even for tea professionals outside the Japanese industry.”

The Matcha Wave

Matcha styles get simplified for other markets, including the United States. There are essentially two: creamy and sweet (Kyoto style) versus dense and more bitter (Tokyo style). Then there is an arbitrary grading system that nonetheless narrows down the field: culinary matcha (for baking and blending), ceremonial matcha (for sipping alone or in drinks), and a third “latte” grade. Chun says quality has to do with grain size, richness in flavor, brilliance in color, and whether the tea is creamy or bitter.

That’s a lot of subtlety to process. So why has matcha caught on with everyday consumers the way it has?

One, it hits the palate differently than anything else found in cafés. Matcha’s umami and slightly bitter, sweet, and grassy notes make up a tight flavor niche similar to what chai stepped into about twenty years ago. Coffee shop patrons likely took to chai not only because it was delicious but also because it was different from what they’d experienced before and rode comfortably on the coattails of familiar flavors like cinnamon and vanilla.

In the case of matcha—in some ways, a drink that requires previous experiences with green tea—its niche can’t be faked by other ingredients. Nothing tastes like matcha, yet it is similarly versatile on a café menu like chai. Matcha shines in dairy milk, plant milk, added as an ingredient to signature drinks, and as a flavor component to baked goods. Tack on its health appeal, and the tea starts to feel pretty limitless.

That was the perspective brothers Max and Graham Fortgang took when they created a matcha-focused business in New York City. What began as a desire to bottle ceremonial-grade matcha after discovering it better fueled their New York-hustle lifestyle turned into a need to educate drinkers on matcha’s potential. To do that, they needed a café. In 2014 the Fortgangs opened Brooklyn’s MatchaBar in the hopes of converting drinkers one latte at a time. “Thousands of people came in the door and had long, sometimes fifteen-minute conversations with us about matcha,” he says. “You need to get people’s palates to evolve slowly.”

That was the perspective brothers Max and Graham Fortgang took when they created a matcha-focused business in New York City. What began as a desire to bottle ceremonial-grade matcha after discovering it better fueled their New York-hustle lifestyle turned into a need to educate drinkers on matcha’s potential. To do that, they needed a café. In 2014 the Fortgangs opened Brooklyn’s MatchaBar in the hopes of converting drinkers one latte at a time. “Thousands of people came in the door and had long, sometimes fifteen-minute conversations with us about matcha,” he says. “You need to get people’s palates to evolve slowly.”

Unlocking the Benefits

Opening a matcha business in coffee-saturated New York City was a courageous move. But it’s paid off for the Fortgangs, who opened their second location at the end of last year.

Drinks like a cinnamon hemp matcha latte, a cucumber lime spritzer, and a matcha chai have helped MatchaBar draw coffee drinkers and more skeptical consumers. Graham says customers often begin with sweeter specials but eventually gravitate toward straight matcha.

At the beginning of this year, the brothers finally launched their bottled, ceremonial matcha in Whole Foods. They’ll continue to serve matcha lattes and the new bottled brew in various venues. Their educational matcha pop-ups have found new drinkers at TED events, corporate offices, and even in Tokyo (their Tokyo pop-up had people queueing for up to three hours).

Flavor is the catalyst for converting drinkers, says Graham, but the real goal is waking people up to matcha’s healthy appeal. Matcha is shade-grown tea and one of the rare drinks where you drink the whole leaf and has proven health benefits. There is less caffeine in a serving of matcha than coffee (typically about two-thirds as much) but more antioxidants and nutrients than a typical cup of tea. Matcha also has amino acids like the stress-busting l-theanine, responsible for the calm alertness that matcha drinkers swear by.

Growing Matcha’s Profile

Science combined with a laser-like focus on flavor has taken coffee to heights many probably never dreamed possible. The same thing is happening with tea, and matcha is reaping the rewards of that expansion, even if knowledge of its origins is still thin on the ground. Companies like MatchaBar and Yunomi, and Mizuba Tea Co. in Portland, are seeking to grow matcha’s profile while educating on its cultural significance and keeping the tea farmer-centric.

It seems to be working: more slow-bar style (ceremonial) matcha is popping up in cafés, and more consumers are asking questions about matcha’s heritage. At the same time, matcha’s culinary use shows no signs of slowing. That’s matcha’s ace in the hole—even if we don’t see more people drinking it straight, chefs will still be enjoying its charms.

Black teas, oolongs, and other green teas currently don’t compete with matcha in terms of food. Because matcha comes in a powder form and has a distinct flavor, a little goes a long way. It’s simple to integrate matcha into products like simple syrup, ice cream, croissants, chocolate, noodles, and beer. Kings and warriors may have imbibed the drink first, but today chefs, brewers, bakers, and bartenders are spreading the flavor to the masses.

Pretty soon, walking into a grocery store and grabbing a cold bottle of matcha might be a reality in places beyond New York City and Portland. This green tea is an acquired taste, but for whatever reason—its gift of focused energy, its surprisingly complex flavor—drinkers are anything but deterred. In the meantime, I will probably continue dreaming about wild ways to serve it. I’m crossing my fingers for matcha gyoza next.

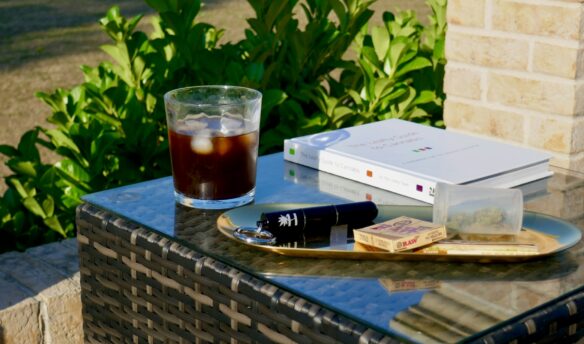

Garden Party Matcha Old Fashioned

Classic drinks like this one take on a fresh flavor and hue with the easy addition of matcha powder. This drink’s grassy, umami notes shine beautifully—a flavor profile that has infiltrated drink culture and is here to stay.

2 ounces bourbon

0.5 ounces of matcha simple syrup (see below)

2 dashes of Scrappy’s lavender bitters

Pour the matcha syrup into an old-fashioned glass, saturate with the bitters, and then add a dash of water. Fill the glass with ice cubes or one large cube, and add the bourbon. Stir gently and garnish with a cherry.

Matcha Simple Syrup

0.5-ounce culinary matcha powder

2 cups water

2 cups cane sugar

Bring ingredients to a boil in a saucepan, stirring gently to break up the matcha. Reduce heat and simmer for three minutes. Pour into a glass jar to store. The syrup keeps in the fridge for about two weeks.

(Recipes by Joni of Mint & Mirth, mintandmirth.com)

Regan Crisp is a writer based in Portland. Cover photo by Ripley Elisabeth Brown ? ៚ on Unsplash

This article was originally published on February 8, 2016, and has been updated according to Fresh Cup’s current editorial standards.