In eighth-century Tang Dynasty China, Lu Yu wrote in the Cha Jing, or Classic of Tea, “During the first boil, add a measure of salt appropriate to the amount of water to harmonize the flavor.” He believed that salt would neutralize any flavors or aromas present in the water and allow the flavor of the tea to shine through.

While Yu likely knew that good-quality water needed no additives, he understood that many reading his book would not have access to the best water, and adding salt would help. One could say this was the first known attempt at controlling tea water to elicit a desired outcome in flavor.

In modern times, it’s relatively well known that when preparing tea, an essential consideration outside of tea quality is the choice of water. Good-quality water can elevate bad tea into something palatable, whereas poor-quality water can make good tea undrinkable.

Many teashops boasting custom water systems hear from customers how much better the tea tastes when prepared at the shop, as opposed to when customers brew the same tea at home. Sometimes this can be attributed to incorrectly followed brewing instructions regarding tea-to-water ratios, water temperature, or steeping time. However, the most common reason for inferior tea at home is a result of the water quality.

Three significant factors must be considered when looking at what makes good water for preparing tea: the pH (power of hydrogen) level, TDS (total dissolved solids), and water hardness.

pH Scale

The pH scale ranges from 1 to 14 and defines the water’s acidity or alkalinity (basicness)—ideally, the more neutral the water, the better. A pH of 7 is neutral, although anywhere between a slightly acidic pH of 6 to a slightly alkaline pH of 8 is considered acceptable.

Drinking water in the US is considered normal within a pH range from 6 to 8.5, so pH is generally not too big an issue when considering what water to use.

TDS

TDS measures the total quantity of minerals present in water and the amounts of metals, salts, or any other impurities that may have been dissolved. TDS is measured in ppm (parts per million) or grains, and 17 ppm is equivalent to approximately 1 grain.

TDS is the most commonly stated metric for qualifying what type of water to use with tea. But the measurement is unreliable without knowing which combination of dissolved solids makes up the TDS in the water you’re using. Hence, a TDS meter may give you the desired reading but still not guarantee the best water. Relying on TDS measurements makes sense when you can control the dissolved solid content.

Water wizard David Beeman of GC Water recommends water with a TDS measurement between 50–150 ppm or 3–9 grains. Beeman has formulated water for hundreds of businesses, large and small, and crafted water guidelines for the Tea Association of the USA.

He cites 150 ppm as the ideal amount of TDS in water for tea, provided the water is run through a reverse osmosis system, which filters the water completely, then reintroduces a mixture of calcium, potassium, and sodium to meet the suggested TDS measurements. Unlike coffee, no magnesium is added, as it makes tea taste over-extracted and metallic in flavor.

Water Hardness

Water hardness makes up part of TDS but should not be confused as being the same measurement. Water hardness describes the amount of calcium and magnesium in water.

Tea tastes best when the water hardness is between 17–68 ppm or 1–4 grains. Too high (over 120 ppm), the tea tastes flat and lacks flavor. At this hardness level, the brew clouds over—especially in iced tea—and an oily film forms on the water’s surface. When water hardness is too low (below ten ppm), tea becomes bitter and astringent, and color may be reduced. Clarity will not be altered.

Ideal Water

Although the US drinking water system is mainly safe, not all tap water is ideal for tea-making.

As a business, the best long-term solution is to send your water to a filtration company, which can test your water for free and recommend a filtration system suited for your particular water. A reformulation unit may be necessary for areas where TDS and water hardness are not optimal.

A secondary solution would be to utilize a bottled water service, and any service should offer an analysis of its water showing pH, TDS, mineral, and metal content. Based on the abovementioned parameters, you can identify whether the water would suit your needs.

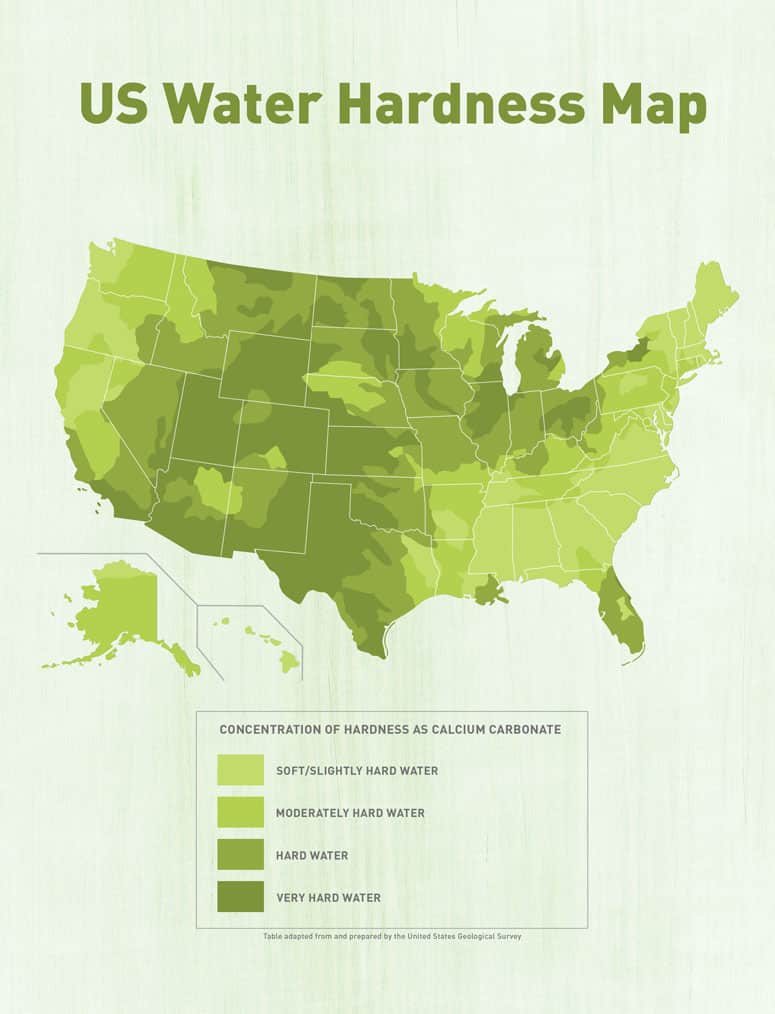

Last, if using locally provided drinking water is your only option, there are several ways to get a good idea of your water’s chemical makeup. Your municipal provider is required by law to issue an annual water quality report. The US Geological Survey has a great map showing water hardness levels throughout the fifty states and Puerto Rico.

A titration kit, mentioned in Fresh Cup’s Water Issue, is a great way to test for water hardness. Titration testing kits, a pH meter, and a TDS meter can all be purchased online inexpensively. Chlorine in drinking water can be easily remedied using a store-bought filter.

We are just starting to explore how water affects tea. Hopefully, this knowledge can be broadened and disseminated in the coming years, raising water quality for every cup of tea.

Cover photo by Harry Cunningham