In many neighborhoods, the first sign of gentrification—a community changing and displacing longtime residents—is when a coffee shop opens.

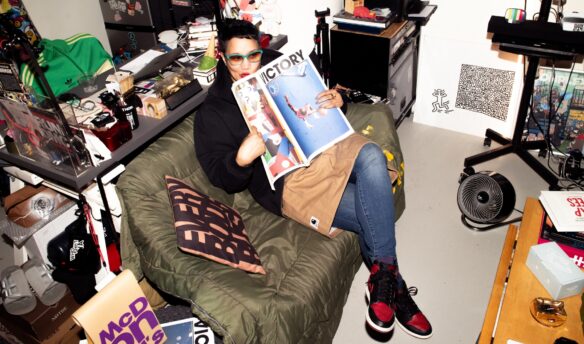

Renata Henderson and Bartholomew Jones wanted something different for their Memphis neighborhood. The couple started a small roasting business called Cxffeeblack in 2020, which “intended to reinstate the origin, purpose, and integrity of cxffee through the knowledge of its Black history and being a part of its Black future,” according to their website. They aimed to create an entirely Black coffee supply chain—from where they source their beans to the spaces where people could come together and connect.

In 2021, Henderson and Jones opened the Anti Gentrification Coffee Club, a space that works to lay claim to the neighborhood and the people who live there. However, Henderson and Jones opened the Anti Gentrification Coffee Club not just for their community but for their family. The couple wanted a space where their boys—ages eight, seven, and three—would see their culture reflected to them and would be able to witness their parents work hard and pour back into the neighborhood.

We chatted with Henderson and Jones about how they built their brand, the significance of creating an all-Black supply chain, and how Cxffeeblack and the Anti Gentrification Coffee Club have fostered a deeper connection to coffee, their neighborhood, and their history.

Can you tell us more about the Anti Gentrification Coffee Club?

Bartholomew Jones: We’ve been open since early 2021. But it has never really been a coffee house; it’s more like a clubhouse. It was a blank room where we would do fulfillment [for roastery orders], and my neighbors and my friends would just kick it, so it was like zero coffee. I had a little pour over setup, but slowly, it grew into more of a shared space for people. But we didn’t have regular hours; it was like, “Hey, I’m open, I’m here. Come through.” For the last year, it’s been more consistent.

I think being able to build spaces for families and communities, specifically for Black and brown families and communities, is really cool to me. Because we don’t get a chance to really do that, and so it’s taking the chance to build it ourselves. It’s dope to me.

Renata, you’re the roaster for Cxffeeblack, but you’re also the first Black woman coffee roaster in Memphis—how did you get into roasting?

Renata Henderson: The conversation initially was, “Hey, we would love to build out our supply chain from Ethiopia to Memphis,” and making sure every part of that supply chain was Black.

Then, when we were talking about roasting, we realized that historically, Black women—Ethiopian women specifically—were the first roasters on the planet. We wanted to honor that, and as people of faith, we know that there are blessings that come through honoring the way God intended things to be. We wanted to honor the history of this practice.

You have three kids: how have you incorporated them into your work? Are they interested in coffee? How is your business a reflection of your family and values?

Henderson: I used to take our youngest son with me everywhere. I have a video of him in his travel crib at the roaster, and he looked over at the beans—this would have been just months after he turned one. And I was like, “Is that cool to you?” He was like, “Yeah, yeah.”

The other day, we were all hanging out at the shop, and I was in the roasting room. He came back and started looking at the knobs on the roaster and asking, “What’s that, Mommy?” And I said, “It’s the roaster. Do you remember it?” Of course, he doesn’t really, but there is a familiarity, and having them in our space allows them to be inquisitive.

Our middle son has a lot of questions about how all of this connects to his identity. He’s like, “Mom, are we from Africa?” and I tell him, “Yes, we are.” We get to have a lot of great conversations about identity, the way God created us, and how we can thrive on Earth while we’re here in the little bit of time that we’re here. We get to talk to them a lot about how that connects—how what we’re doing connects to them.

My husband talks to our oldest about it; he calls him our barista in training. Now he’s very interested in the drink side of it. The other day, Bart told him, “This business is going to be yours one day. How does that feel to you?” And he was very reflective. I don’t think he’s answered that yet.

It’s a big conversation. We keep having it, and we’re going to keep having it. We’re telling them, “This is your inheritance.” And again, we’ve tied a lot of what we do back to our faith.

Jones: I wanted to own an institution in my neighborhood because I wanted to be able to shape what was normal, what was perceived as normal, and the institutions that define normality. And a part of the conversation we’ve been having with other kinds of grassroots organizations and educators and people in Memphis is how much of what is seen as normal in our neighborhoods is defined by people who either don’t live there or have no vested interest in the beautiful things about our culture. It’s almost like this weird brainwashing that happens.

When my kids get out of school, we pull up to the shop, they go to the backyard behind the shop or the coffee club, and there’s a basketball hoop and a slide out back. And then they run into the middle of the cafe from the backyard and jump on the floor. They’re having fun; it’s a part of their life. People are used to seeing me, my wife, and the boys in the neighborhood and in the shop. I get to change the conversation of what’s normal.

Why was building an all Black coffee chain important to you?

Jones: Many of the things that we’ve been given, even a lot of traditional foods that are considered to be African American, like chitlins—these are things my ancestors had to have because that’s all they were given. Traditional foods were not allowed to be institutionalized in their community, and that’s a holdover from the slave trade. It’s a holdover from Jim Crow.

There’s a documentary on Netflix called High on The Hog, and we hosted a screening at the shop recently. There was a moment when the host interviewed a descendant of sharecroppers, and he explained that there was a time when we were still living on the land, but we weren’t getting paid what we deserved for our labor. Then, all these people who were sharecropping just cut the contracts with us and kicked us off the land. So, we had to move into the neighborhoods that are called ghettos today. It was a prepackaged experience, and it meant that many Black people were disconnected from the land, no longer able to choose or grow their food.

The institutions in our communities are corner stores and liquor stores. Then, once money starts coming in, those institutions are no longer owned by the community. In comes the coffee shop—the coffee being served there, the music being played, the activities—none of them are aimed at reflecting or honoring the root of the community. So we wanted to change that.

Small acts of self-determination are really revolutionary to me. That’s what I love the most about coffee: it’s a moment where you get to have space for yourself and for your senses. Space to reconnect to something from the soil, from the same soil we’re from. In some small way, coffee can connect us back to a part of our humanity that I think is lost. We get to expand that autonomy into reconnecting to ourselves and see ourselves in a way that is more congruent with who we actually are.

Even if it’s just saying, “Hey, me and my kids are going to sit in front of the shop and make beats today,” or we’re going to put the game on and put on a Congolese coffee and espresso—I want my kids to be able to see that. And unfortunately, there are just no spaces outside of our house where Black kids get to see the best part of their culture reflected back to them. There’s something powerful to me about getting to choose what my kids grow up around.

Coffee can be a difficult business, particularly for families. How have you worked together to both raise your kids and build a business?

Henderson: I think what added value was that, in an industry where you’re encouraged to isolate and really just put your nose to the grind and just go, go go, we approached Cxffeeblack as what we’re doing as a family. There is no “I’m doing this alone.” If we’re going to commit to this, we’re going to commit as a family.

A lot of times, when you take children into spaces, especially coffee spaces, there’s pressure to tell your children to “be quiet while we’re in here.” It’s wild to tell a child to not be a child. We had to stop and think about every step we made and make sure that our space was welcoming for the Black community, and that includes children.

We’re trying to teach our children to love those society writes off and care for and make space for those people. It’s wonderful to be able to say everybody can come in and experience the warmth of our coffee club. Everyone deserves that love because it was given to us. We receive it, and we give it.

One of the company mottos on your website is: “May your hood lack no coffee nor peace.” What does that mean to you?

Henderson: “Buna fi Nagaa hin Dhabiinaa” is an Ethiopian blessing that means “may your house lack no coffee nor peace.” And what the way we spin is “where there’s coffee, there’s peace.”

That is how we introduce people to our coffee. Our people took it very seriously, created a blessing, and even created democratic practices around it. We learned about something called buna qalaa this past year when we were in Ethiopia. It’s a 2,000-year-old practice that they use for weddings and births, but they also use it for conflict resolution.

When they’ve reached the end of their discussions, they do buna qalaa. When we were in Ethiopia, we got to experience buna qalaa. Of course, we didn’t experience it within the context of conflict resolution. Still, we learned how conflict affects everyone on a community level, and the only way we can move forward as a community is by addressing it and making a seat for peace. Hearing that coffee is used to bring peace back between conflicting parties within the community was amazing.

So that’s how it became one of our company’s mottos: where there’s coffee, there is peace.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.