[A]s ever greater appreciation of the variety of coffees and their nuances leaves the cupping lab and enters the minds of regular folks, there’s a sidecar desire for more and more information about the beans dosed into shots at a café or poured into home grinders. I was chatting with Jon Allen, the owner and roaster at Onyx Coffee Lab, about the information he presents on his labels and, as the conversation turned to this growing sophistication, he said customers have begun asking what natural process coffees he offers. Customers are asking for particular processes. In Arkansas.

So, roasters, job well done on the education front, but obviously this has caused a major conundrum: how do you talk about your coffees when one customer wants to know elevation and the other wants something Italian? The approaches, not surprisingly, have been widely divergent.

It could be useful to see what other industries have done. Many coffee people point to wine as a compatriot that’s blazed similar paths coffee is on or headed to. To find out how wine settled on its descriptions I talked with Paul Lukacs, the author of several books on wine including The Invention of Wine.

“Nobody says to you, in France, ‘You mean sauvignon blanc?’ No, you want a bottle of Sancerre.”

In the book, Paul recounts how terroir and its effect on grapes was first articulated by Cistercian monks in, naturally, Burgundy around the turn of the first millennium. The all-importance of terroir has stuck so hard in Europe that varietal is hardly even considered. “You want a bottle of Sancerre,” Paul says. “Nobody says to you, in France, ‘You mean sauvignon blanc?’ No, you want a bottle of Sancerre. It’s made out of 100 percent sauvignon blanc, but no one thinks in terms of varietal because nothing else can legally be planted there and called Sancerre.” Paul even says that if a bottle of European wine displays the varietal it’s because it was destined for export to the States.

Americans and Australians talk about their wine differently simply because the growing regions are so young and the experiments with what grows best where are so expansive that no varietal is synonymous with any one place. Starting after World War II, vintners began using the varietal to describe their wines. This was especially driven, Paul says, by a desire to go toe-to-toe with French wine. In the seventies, “Californian” wine denoted nothing, but cabernet sauvignon could compete with red Burgundy.

Advance four decades and grocery stores organize hundreds of wines from dozens of regions by varietal. Paul suggests this might not be the end. “Starting this century, which is now fourteen years old, there are people who are beginning to focus as much attention on place,” Paul says. “The person who thinks about this more says, ‘I really like Willamette Valley pinot noir, but I really like the ones from Dundee Hills.’” Now that person still says pinot noir, not simply wine, but there could come a day when a customer grabs a bottle and knows its merlot because it’s from Walla Walla, no label ID required.

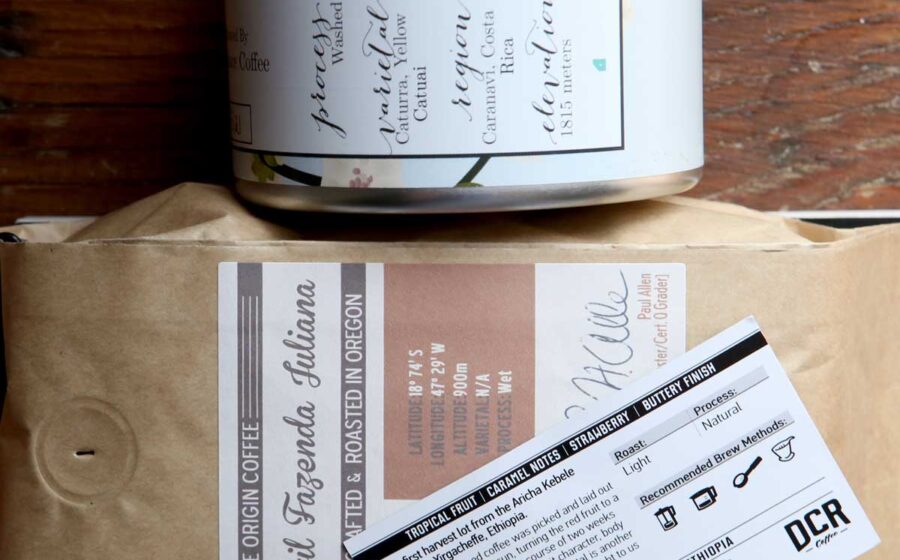

This by no means proves terroir should or will be coffee’s primary descriptor. Varietal, processing, certification, tasting notes, roast, all of these have a claim on best describing what’s in a bag. It could point to both a simpler and more complex way of describing coffee: bare-bones info for your general audience blends, reams of information for mid-level single origins, and a sole place name for your $30 eight-ounce superstar.

—Cory Eldridge is Fresh Cup’s editor. He’d really like to hear your thoughts on how you talk about coffee. cory@freshcup.com