Lush countryside, rolling rivers, and an active, majestic volcano are among the indelible sights adorning Turrialba, a small city in Costa Rica’s Central Valley. Nestled in this charming origin landscape is a white-and-red, Mission-style building that may be one of the most important institutions to the future of coffee.

This sprawling entity is the Tropical Agricultural Research and Higher Education Center (better known as CATIE)—an institute devoted to agricultural development and biological conservation—and among its prized holdings is a gene bank of seeds of nearly 2,000 varieties of coffee.

Gene banks like the one at CATIE have received increased attention in recent years. Rising temperatures and other symptoms of our changing planet have raised questions about coffee producers’ ability to grow a sustainable supply of coffee. Gene banks preserve coffee’s genetic resources, providing source material researchers can draw on to potentially breed the coffee varieties of the future.

Maintaining these gene banks is the focus of the Global Conservation Strategy for Coffee, a recent partnership between World Coffee Research and Global Crop Diversity Trust (better known as Crop Trust) to ensure coffee’s diversity. With coffee’s genetic resources being lost at a rapid pace, the strategy aims to unite the industry to preserve this precious material. As World Coffee Research Executive Director Tim Schilling puts it, “We have to step up and take control of the genetic resources that dictate the limits and open the possibilities for the future of our industry.”

Preservation In The Bank

An estimated 125 million people in over seventy countries depend on the coffee value chain for their livelihoods. Those on the production side have seen higher temperatures, droughts, diseases, and a host of other climate-related factors contribute to decreased yields and quality. In 2016, the Climate Institute released the report A Brewing Storm, presenting a stark forecast for coffee’s future: “Climate change is projected to cut the global area suitable for coffee production by as much as 50 percent by 2050,” it read.

Further challenging coffee’s future is that arabica—the species behind specialty coffee production—has become extremely “genetically constricted.” This constriction is primarily due to arabica’s history, as most of the varieties grown today descend from a handful of plants that left Yemen on colonial trade routes.

Also contributing to the loss of genetic diversity is the centuries-long tendency of coffee producers to gravitate toward cultivating arabica that performs well in cup quality and yield. “What that means is that arabica has become very susceptible to the same issues,” says Brian Lainoff, lead partnerships coordinator of Crop Trust.

With more genetic diversity comes more options for surviving these issues; World Coffee Research’s Hanna Neuschwander offers the analogy of a toolbox. “You can do a little with a hammer, but you can do a lot more with a hammer, a wrench, and a screwdriver,” she says. “The more genetic diversity, the bigger the toolbox for solving problems that come along.” The gene bank might just be the ultimate toolbox for building coffee’s durability.

So how do gene banks work? For the world’s crops, gene banks house seeds from an extensive assortment of varieties, including both active varieties and those no longer found. Gene banks conserve and catalog these varieties and share them with the following:

- Plant breeders, who cross-breed varieties with other species to attempt to develop new varieties that can survive in increasingly harsh climate conditions or other future challenges (e.g., the emergence of a new disease).

- Farmers, who can request samples of crops to see how they fare under conditions on their farms.

A 2016 article in Yale Environment 360 called these facilities “the lifeblood of the international agricultural community,” This work is vitally important to ensuring the world’s food supply. “Take rice, for example,” says Lainoff of Crop Trust. “There are 200,000 varieties of rice, so it’s actually quite a large genetic base. But a plus-one degree temperature increase equals a minus-2 percent yield per decade. That could mean global famine, or it could mean problems for farmers around the world.”

While coffee may be considered more of a luxury product than a subsistence crop, it does account for the livelihood of hundreds of millions, not to mention a total world market estimated at over $173 billion by the International Coffee Organization. And coffee gene banks have directly affected the diversity and vibrancy of the coffee we drink—the revered gesha variety wouldn’t have been discovered without CATIE’s role in preservation.

A Strategy For Preservation

Seeing the vital role of gene banks in coffee’s future, World Coffee Research partnered with Crop Trust and launched the Global Conservation Strategy for Coffee. Leading the strategy is Sarada Krishnan, director of horticulture and the Center for Global Initiatives at the Denver Botanic Gardens. The strategy’s goal is to:

- Shore up funding and resources for key coffee gene banks.

- Ensure accessibility of bank resources.

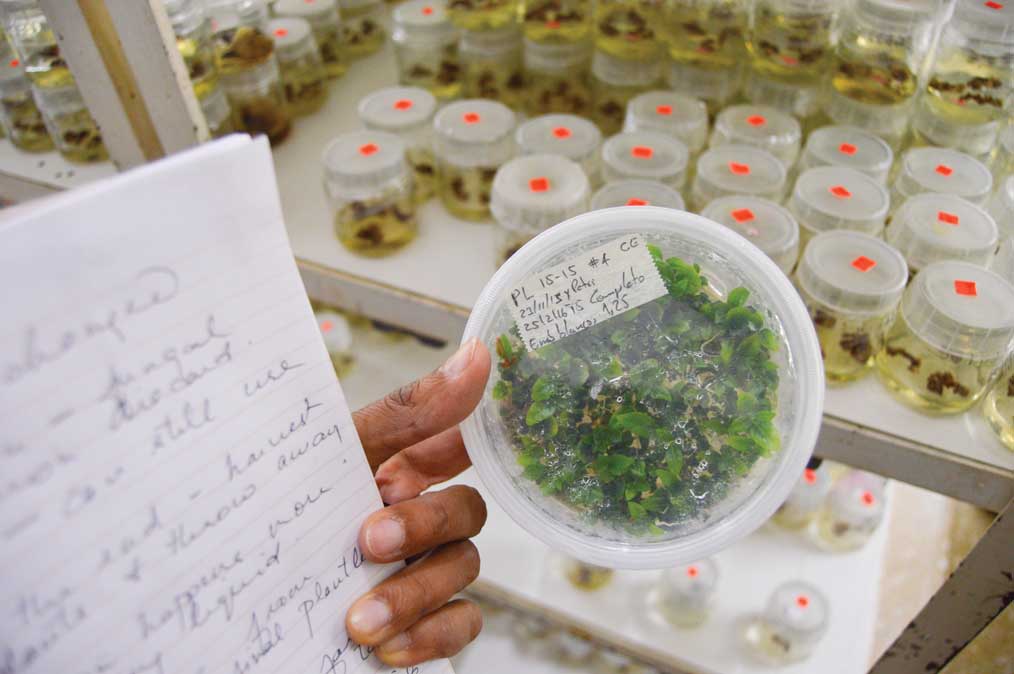

To the first point: maintaining gene banks is incredibly expensive. While most grain crops are stored through freezing—a measure taken so crops can last hundreds of years and still be planted again to yield new crops—this is not the case with coffee. Because it’s a tropical crop, coffee is preserved in expensive-to-maintain “field” gene banks that house row after row of coffee trees—called accessions.

Unfortunately, many of coffee’s most essential gene banks are struggling, and as a result, some of the genetic resources they contain are being lost as trees die for lack of upkeep. While CATIE and other gene banks in Latin America are relatively sophisticated, they still lack the funds to fully maintain their facilities, losing trees every year.

Other gene banks are in more dire need—take the Kianjavato Coffee Research Station in Madagascar, which has a skeleton crew, insufficient tools, and antiquated record-keeping methods. “They have not had resources to maintain it, and so it has gone into disrepair,” Krishnan says. “A lot of the countries that hold these gene banks are resource-poor countries, and when the government doesn’t see immediate results coming out, then they don’t see the need to support them.”

To the second point, the Global Conservation Strategy for Coffee aims to develop a global database—not dissimilar to a library system—to make both information and the plants themselves accessible between gene banks and to researchers and breeders.

Currently, most of these facilities keep records of their holdings on paper, and those that are digitized—CATIE in Costa Rica, for example—aren’t accessible online. “Even though some of these gene banks are keeping these materials, nobody is really sharing or knows what the other gene banks have,” Krishnan says. “There’s limited value in conserving these genetic resources if they’re not going to be used.”

Sharing Resources

CATIE is the only gene bank in coffee that participates in the International Plant Treaty, meaning its collection is available for researchers worldwide to use. Says William Solano, a genetic resources researcher at CATIE in Costa Rica: “We made this decision considering the importance to humanity of protecting and conserving plant genetic resources for future generations.”

Through the Global Conservation Strategy for Coffee, the partners hope to bring other gene banks into the practice of sharing information and plant material. In embarking on this process, the first step was for the partners to reach out to the thirty coffee gene banks in producing countries around the world.

They sent out surveys to discover the facilities’ holdings, maintenance routines, accession methodologies, data storage techniques, and much more. What they found confirmed significant potential for increased sharing: according to the survey, only 1 percent of coffee germplasm resources are being used by researchers outside their host country each year.

After sixteen gene banks responded, Krishnan and the team determined seven facilities that would provide a well-rounded representation of the world’s gene banks. They then hit the road, visiting coffee gene banks in Madagascar, Kenya, Ethiopia, Ivory Coast, Costa Rica, Colombia, and Brazil for an on-the-ground assessment of each gene bank. The team used these visits to pen a strategy document, of which Krishnan is the lead author, along with Dr. Paula Bramel of the Crop Trust. “The document identifies the threats of all these gene banks, and then it talks about some of the high-priority action items that need to happen to protect these coffee genetic resources for the future,” Krishnan says.

The document is scheduled to be finished in April and released at the Specialty Coffee Association’s Global Specialty Coffee Expo in Seattle. (Krishnan and Crop Trust Executive Director Marie Haga will present the project and the document’s findings at the Re:co Symposium before the event.) World Coffee Research and Crop Trust will lead fundraising efforts to create the necessary means to enact the preservation work. “Our hope is that the entire industry will get on board to support the strategy,” says Krishnan. “It’s not just the producing countries—the entire coffee community needs to be part of this. It impacts all of us who depend on coffee.”

Amid doom and gloom prognostications of coffee’s future, the industry has the opportunity to collaborate to take concrete actions to preserve coffee’s genetic diversity and potentially create the varieties that provide the sustainability answers the industry sorely needs. “Coffee could very well depend on this diversity,” says Lainoff of Crop Trust. “The plant is the foundation of the coffee trade. We can’t forget that, and we must do everything we can to preserve it.”

How A Coffee Gene Bank Led To The Rediscovery of Gesha

Perhaps no story illustrates the importance of gene banks to coffee more than the tale of gesha, the beloved variety renowned for its complex floral aromatics and stunning brightness.

Gesha burst onto the specialty coffee scene in 2004 when Hacienda La Esmeralda, an estate based in Boquete, Panama, took the top prize in the Best of Panama competition. Its amazing gesha has since become an institution in specialty coffee, fetching high prices year after year for its coveted cup, while coffee producers worldwide have planted gesha and reaped the delicious rewards.

But gesha wouldn’t have taken root at Hacienda La Esmeralda without the presence of a coffee gene bank—specifically, the Tropical Agricultural Research and Higher Education Center (CATIE) in Costa Rica. Native to Ethiopia, gesha was originally collected on an expedition in the 1930s by British Consul Richard Whalley.

The variety made its way to CATIE in the 1950s; in the 1960s, a Panamanian government employee named Pachi Serasin was sent to CATIE to find new coffee varieties. He returned to Panama with three or four varieties—one of which was gesha—and distributed it to farms in Boquete. One of the lucky recipients was Hacienda La Esmeralda, though it would take a while for anyone to realize the power of the variety.

Price Peterson and his family bought Hacienda La Esmeralda in 1997, and Price says that at the time, the farm produced a “generally good coffee” rather than an extraordinary one. In the early 2000s, the farm’s trees faced an outbreak of a fungal infection, and Price’s son Daniel noticed that one variety appeared to be less affected by the outbreak.

This variety was gesha. Though the trees at Esmeralda were low-yielding and not outstanding in the cup, Daniel had the idea to plant gesha at a spot on the farm with a much higher altitude (around 1,600 meters), suspecting this new placement could extend the coffee’s ripening time to create additional sweetness and acidity. The rest, as they say, is history, as the Petersons uncovered the outstanding quality potential of the fantastic variety.

CATIE’s role as a conserver of resources directly contributed to gesha’s eventual discovery and worldwide celebration. Since finding gesha through CATIE, the Petersons have repeatedly returned to the gene bank to unearth other hidden treasures, trying as many as 400 varieties.

“Once gesha came out, my idea was there has to be something better than that,” says Price Peterson. “But we haven’t found anything that tastes better than gesha.” Still, the Petersons view CATIE as an invaluable resource for specialty coffee. “The gene bank at CATIE has been incredibly important to us,” Price says. “We need to depend on these gene banks to keep our genetic diversity going.”

This story was originally published on April 17, 2017 and has been updated to meet Fresh Cup’s current editorial standards.