Robusta seems to be enjoying its moment in the sun. This year, World Coffee Research (WCR) published its catalog of Robusta varieties and a report on the future of Robusta quality. “The market for robusta (coffee of the C. canephora species) has seen astonishing growth in the last few decades—rising from 25% to 40% in the last 30 years,” the WCR report reads. “This growth represents a major share of all global coffee demand growth. Demand is not expected to slow down—the coffee markets with the highest growth rates and youngest populations are all markets that currently consume primarily robustas.”

At the same time, US coffee drinkers are becoming more aware of higher quality Robustas thanks to Vietnamese-owned roasteries like Nguyen Coffee Supply, Viet Five, and Portland Cà Phê Roasters, all of which sell Vietnamese-grown Robusta beans. On the other side of the Pacific, Vietnam, where Robusta grows in abundance, hosts a booming and vibrant specialty coffee scene fueling quality improvements in Robusta farming.

But this upturn for Robusta comes after years of unpopularity and disdain. The specialty coffee sector turned its nose up at Robusta due to its poor reputation as a cheap commodity coffee often used as a component in large, instant coffee brands. The review website Coffee Review pulls no punches in assessing an instant coffee blend from Folgers, for instance, as an “anthology of coffee taints” due to an aroma “dominated by a rotten dried-in-the-fruit Robusta note.” What’s taking place in the Vietnamese specialty scene, however, is removed from perceptions of commodity Robusta. Besides improving farming and processing practices, farmers and researchers are also experimenting with new cultivars that make a case for reconsidering Robusta .

Espouse Modernity, Embrace Tradition

At a glance, focusing on Robusta coffee through the lens of Vietnam makes sense. “If anyone knows how best to reinvent robusta,” writes Alina Simone in The Atlantic, “it would be the coffee farmers, roasters, and brewers who have provided the world with the bulk of it for decades, and whose domestic customers have never stopped enjoying it.” Thanks to the 1987 Đổi Mới reforms and transition to a socialist-oriented market economy, the country has become the world’s second-largest coffee producer and exporter. Robusta comprises more than 95% of its output, a fact not lost on many Vietnamese coffee professionals.

Another reason Robusta is central to Vietnam’s coffee culture is its key role as an ingredient in many traditional coffee drinks such as cà-phê sữa (black coffee with condensed milk), cà-phê trứng (egg coffee), and cà-phê dừa (coconut coffee)—these drinks simply aren’t the same without Robusta as its base. In her 2022 survey of Vietnamese specialty coffee, journalist Molly Headley notes that newer specialty cafes heartily embrace existing local coffee traditions instead of eschewing them in favor of espresso drinks: “Many specialty cafés in Saigon feature traditional Vietnamese coffee beverages on their menu upgraded with top-quality beans…” Headley observes. “In other words, it’s not about erasing Vietnam’s coffee culture[.]”

General coffee drinkers in Vietnam enjoy dark roast Robustas since they pair wonderfully with condensed milk, which is used in many traditional Vietnamese coffee drinks. The custom began when French colonizers in the late nineteenth century used condensed milk in their coffee in lieu of fresh milk due to the lack of refrigeration. “Condensed milk, which is sweet and dense, became prominent in Vietnamese coffee culture because it doesn’t need to be refrigerated,” explains Sahra Nguyen from Nguyen Coffee Supply in an interview with the culinary website Taste. “Coupled with the fact that Vietnamese coffee is primarily robusta…those flavors meld together. Sometimes when you add dairy milk, or sugar, or condensed milk to a citrusy, fruit-forward arabica, it doesn’t vibe and can be kind of sour.”

Saigon-based 96B Roastery owner Hana Choi opened her specialty cafe and roastery very much with local preferences for dark-roast Robustas in mind. “I want local Vietnamese people to come, taste my coffee and find it agreeable first before I introduce light roast, more acidic coffees to them,” she explains via email.

“I myself would only drink filter black coffee, no sugar, no milk. But the local people here are acquainted with the taste of Robusta that is dark, strong, syrupy, caramel, nutty, and bittersweet. I grew up tasting and experiencing ‘cà phê sữa dá’ [iced coffee with condensed milk] in many different forms, so I knew the coffee flavors that ran in the blood of traditional Vietnamese coffee drinkers.” Choi bridges the gap between traditional and modern at her cafe, including having a phin, a traditional brewing device used in Vietnam, next to a V60 and Chemex in 96B’s instructional hand brewing workshop.

Duc Le, the roaster and owner of Cafe Le J’ in Dalat, argues that Vietnamese coffee drinks rely precisely on Robusta’s bold profile. “It cannot be replaced by any other coffee variety due to its distinct flavors and intriguing stories,” he says. “Many popular coffee-based drinks in Vietnam…rely on the robust flavor profile of Robusta.”

Le does not believe that Robusta is inherently inferior to Arabica because the former’s “unique qualities, including low acidity or no acidity, a rich body, and bold notes of nuts and chocolate, cannot be matched even by dark roasted Arabica.” Robusta’s classic cup allows it to stand up against the other components in these traditional beverages.

Reinventing Robusta Through Newer Cultivars

Roasters like Choi and Le are also paying close attention to newer Robusta cultivars from Vietnam. Many reports, hopeful about the future of Robusta, point to its resilience against pests and heartiness in the face of climate change compared to Arabica. Newer cultivar breeding, however, shows increasing interest in taste and cup quality. Without rejecting the traditional Robusta profile, these roasters began featuring new Robusta varieties and experimental processes in their cafes that show a sweeter and more dynamic cup.

The newer cultivars, for Le, occupy a category distinct from the traditional ones: “[To] truly appreciate fine Robusta at its best, one must understand what sets it apart from regular (commercial) Robusta and recognize some of its distinctive flavors.”

Traditional Robusta varieties—Robusta sẻ—“are typically very small and dense (measured by screens that filter out beans based on size: for traditional varieties, they often below screen size 15) with a medium to heavy body,” says Le. “They exhibit subtle flavors of dry tropical fruits, occasional hints of red florals, chocolate, caramel, roasted nuts, and low acidity, resembling the acidity of a red apple (malic acid). The aftertaste carries a sweetness reminiscent of honey or sugarcane.”

In contrast, new Robusta varieties—typically labeled numerically, i.e., TR4, 5, 6, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15—“are larger in size (usually between size 16-20) and have a lighter body,” says Le. “Their flavor profile includes notes of dry fruits such as tropical fruits and apples, delicate floral hints, chocolate, tea-like qualities, roasted nuts, and slightly higher acidity reminiscent of citrus.”

It seems no accident that part of what is driving researchers to breed newer Robusta cultivars is the prevailing specialty preference for brighter, more delicate cup profiles. Now we are seeing more and more Robusta lots that truly stand on their own. “There are already some Robustas that are very pleasant in terms of flavor and tasting notes as well as the balance between attributes,” says Rae Tu Tran, co-founder of Karmic Circle Trading Company. “If I can enjoy a Robusta with a pour over, without milk and sugar, it is a pass in my book for determining whether it is specialty.”

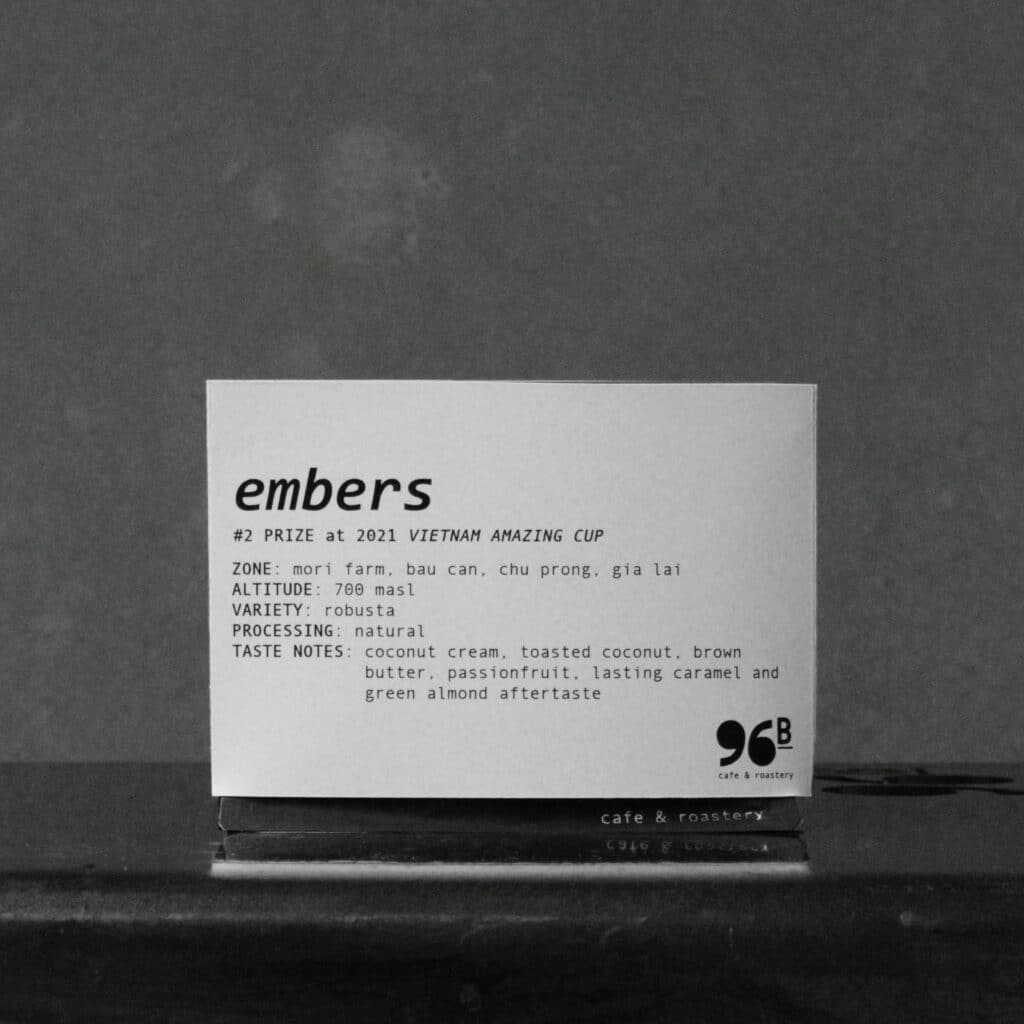

96B has been incorporating Robusta into its espresso blends since opening in 2016. But it wasn’t until 2021 that Choi began releasing Robusta lots as single-origin offerings: “At the time, I did a test roast and cupped the Vietnam Amazing Cup Winner Robusta lot from [Ms. Tran Thi Bich Ngoc of Mori Farm], I had a hunch that now is the right time to showcase Robusta flavor,” she says.

The coffee had “unique characteristics of roasted coconut, caramel candy, winey and creamy mouthfeel, totally different from the flavor profile you would commonly come across in Arabicas,” Choi describes. ”I want to present it to my customers who mostly drink only Arabica coffees.”

Quality improvement in Robustas may be fueled by standards and competitions like the Cup of Excellence that have been used to evaluate Arabica beans. But what Choi found compelling in that coffee was that it demonstrated Robusta’s potential to possess its own identity in quality and cup profile. Choi wanted to offer Ms. Ngoc’s lot as a single-origin release because it tasted unlike Arabica.

Quality or Marketing First?

A 2019 Perfect Daily Grind article by Francesco Impallomeni asks, “Can Fine Robusta be Considered Quality Coffee?” My quick answer, based on the experiences of coffee professionals like Choi and Le, is yes. But the larger issue, as Impallomeni indicates in the article, lies in how to sell it. To sell fine Robusta, quality improvement alone is not enough.

Despite the quality and distinctness of Robusta lots like Ms. Ngoc’s, there’s still a substantial reluctance among specialty coffee drinkers to embrace Robustas. The problem with Robusta’s perception, though, is deep down a problem of commodification. To be fair, the same issues associated with cheap coffee plague many of the world’s Arabicas. As Coffee Review founder Ken Davids contends, “Robustas are cheap and poorly prepared because they are expected to be cheap and poorly prepared.”

Quality Robustas challenge us to consider embracing the species not just in terms of sustainability, but taste. For some, this can make fine Robusta a perplexing category. Its flavor potential distances it from faulty commercial Robustas, but neither does it merely ape the delicate notes we prize in the best of specialty Arabicas. Saigon-based Bel Coffee owner Will Frith, as quoted in Simone’s Atlantic article, captures the confusion well: “Where do you put this thing that’s always been automatically perceived as low-quality when you’re trying to create the high-quality version?”

Professional coffee actors are hardly neutral when it comes to marketing quality in coffee. Anthropologist Edward Fischer, who’s worked closely with Mayan coffee farmers in Guatemala, contends that quality is ultimately not discovered but rather defined. The paradox of Third Wave coffee is that in its pursuit of quality, “these same coffee professionals and enthusiasts are also defining what constitutes quality.” Even with quality improvements in Robusta, coffee actors like importers and roasters wield immense power as tastemakers in determining and curating quality.

Specialty cafes and roasteries can change the narrative around Robustas and create market demand for them. By sourcing and selling fine Robustas, roasteries and cafes can diversify their offerings and sell coffees with a broader range of flavors.

Agro-commodities researcher Mamy Dioubaté deftly sums up the issue in Impallomeni’s article: “I don’t think it’s a zero-sum game where the emergence of Robusta on the specialty coffee market takes away from Arabica market. We should work on coffee quality and diversity. We need to diversify. We need to think about all those people we don’t reach with our current specialty coffee product instead of being worried about the cake getting sliced up into smaller pieces. Let’s make a bigger cake.”

As roasteries like 96B and Le J’ show, Vietnamese specialty coffee provides a model of how to integrate Robustas into a specialty cafe menu. At once juggling tradition and innovation in a region where Robusta farming is ubiquitous, the scene reveals what a gradually maturing fine Robusta landscape can look like. One that not just produces a clean cup by stamping out farming and processing defects but also gives us new flavors.

“You ask for a clean cup because today you can’t ask for anything more,” echoes one respondent in WCR’s report. “But if you have a chance to get robusta with other characteristics, what else do you want? If we limit our thinking to the present, we have no chance to do something new. If we find a new flavor profile, maybe there is a new opening in the future.”

Cover photo courtesy of Cafe Le J’