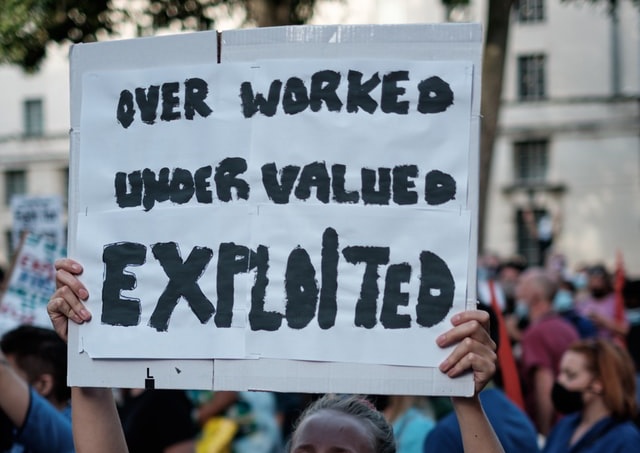

A global traumatic event that hurt poor people more than rich people. A labor shortage. Low wages. Uneven economic gains between corporate leadership and employees. Underemployed and underpaid educated laborers. Frustrated and emboldened workers. A pro-labor president.

It might sound like I’m describing the current status of the United States workforce, but I’m actually talking about the US in the mid-to-late-1930s. After the 1929 Wall Street crash, the Great Depression was loosening its death grip on the global economy. Executives were doing exceptionally well, but the average US worker was still struggling. Wages had stagnated, workdays were long, there were few protections for workers on the job, and no safety net should they become injured or die. It was the perfect storm for a sweeping labor movement.

If the labor movement seems to be picking up steam again—and it is, if the sweep of unionization efforts through Starbucks locations is any indication—it’s because we’re back in a similar spot today. For sectors of the coffee industry considering how the power of collective bargaining might improve their lives, it’s worth looking at the history of US unions.

Unions, A History

Unions have operated in the US since the 1794 formation of the Federal Society of Journeymen Cordwainers in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Early unions were usually local trade affairs, organized around crafts like tailoring and shoemaking that required long apprenticeships and training. National unions soon followed, uniting all workers within a craft to standardize prices and bargain for better treatment.

Factories were not usually settings for early unions, but 150 years later, the end of the Great Depression accelerated the growth of unions in factories. Workers in factories were usually skilled laborers with an above-average level of education, who could see clearly how executives benefited from economic recovery, but how that recovery wasn’t trickling down.

On December 30th, 1936, autoworkers at a General Motors plant in Flint, Michigan, engaged in a sit-down strike, referred to as “the strike heard ’round the world” by the Library of Congress. In 1935, the government had estimated that a family of four needed $1600 annually to live; auto-workers were making $900 annually, and we’re usually the only income-earner in the home.

Meanwhile, GM was making a lot of money. Cars were growing in popularity, and Alfred Sloan, the President of GM, publically boasted he was worth over $70 million, about $1.5 billion today. Workers were critical of how the company could create such wealthy executives but pay laborers less than a living wage. Union membership swelled in the months leading up to the strike.

The United Auto Workers Union already existed but wasn’t recognized by GM and didn’t have the kind of power they needed to accomplish much until the strike in Flint. The auto plant remained shut for six weeks, and violent melees took place between workers and corporate police. At one point, President Roosevelt sent in the National Guard to keep the peace and protect the strikers. After over a month of no work, bad press, and millions of dollars lost, GM recognized the union and gave workers a 10% raise. They’d won.

Corporate Response and Growing Union Power

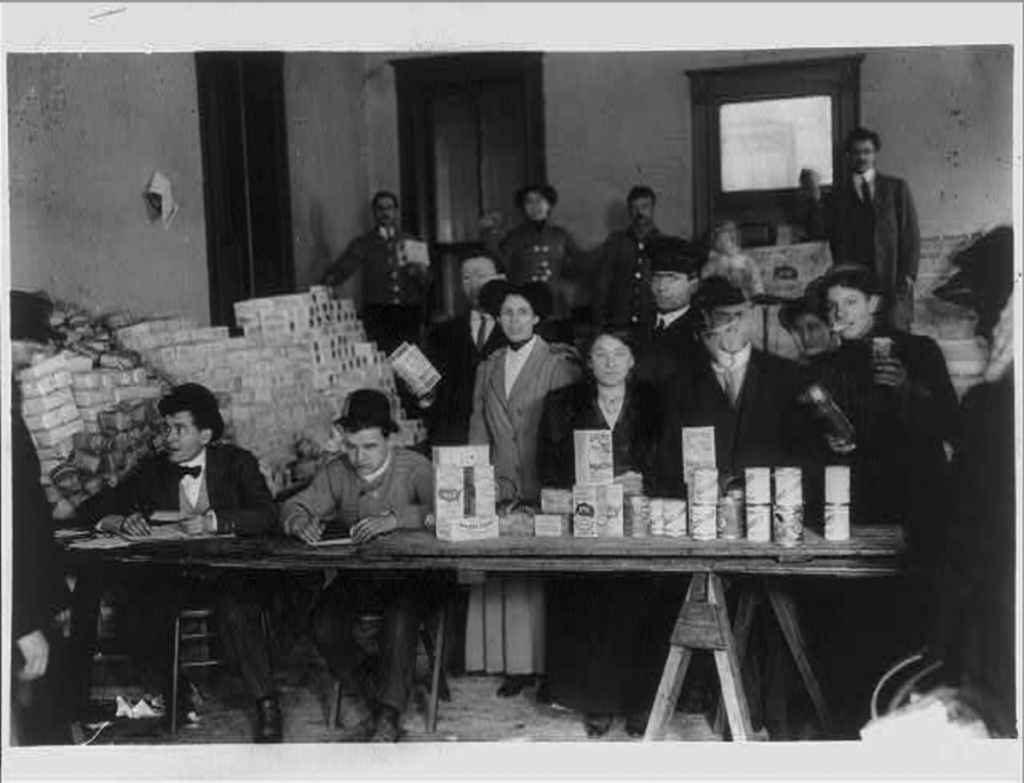

Executives in other industries had watched this story carefully, and the results made them nervous. Companies began recognizing unions to avoid even a possible strike: Textile, food, tobacco, steel, oil, furniture, reporters—industries across the board began to unionize.

Then, in the 1940s, World War II’s outbreak meant a significant labor shortage in every US industry. Some unions took advantage of this, leveraging their power to gain benefits for remaining workers like paid time off and set meal breaks. Despite rhetoric about maintaining labor peace to keep production up for the war (and the technical ban on striking), organizer Jane McAlevey notes in A Collective Bargain that there were 14,471 strikes in the US during this time. Workers knew it was the perfect climate to improve working conditions and committed to strikes anyway, accepting the punishments for striking along with better working conditions.

After the war ended, even more significant national strikes took place. Strikers were standing up against post-war unemployment and lower wages, and their efforts did a lot to lessen the income inequality gap that had emerged in the 1920s, 30s, and 40s. Repeated success saw year-after-year increases in union memberships until just over a third of US workers belonged to a union by the 1950s.

Where Unions Stand Today

In the May 2nd, 2022 episode of “The Daily,” a podcast from The New York Times, labor reporter Noam Scheiber said that this explosion in membership worked like a snowball effect, each successful unionization inspiring others to unionize as well. And today, we may be back at just such a tipping point.

According to Scheiber, petitions for union elections to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) have increased 60% since December 2021. A petition for an election means workers have asked to vote to form a union, with the NLRB overseeing that process—it doesn’t mean that each workplace has a fully-recognized union. But this surge is a dramatic change to the patterns of the labor movement since the 1970s.

After the 1950s, union membership dropped dramatically. The “one in three workers” statistic represented the height of union membership: by 1977, only 25% of workers belonged to a union, and by 1997, that number was just 14%. After decades of legal battles that weakened unions, among other factors like globalization and shifts in trade, only about 10% of US workers are currently in a union.

Since 2017, however, the coffee industry has seen record-setting unionization efforts across the United States. From the story of Augie’s Coffee in California and their union-busting retaliation of workers; to the dozens of unions at Starbucks; to the story of Morning Bell, an Iowa-based coffee roastery that became a worker-owned cooperative with support from the former owners; unionization efforts within coffee have seen increasing success.

Considering that circumstances today are the same—or worse—than the Great Depression, this is hardly surprising: We’re facing a third recession in as many decades; the federal minimum wage hasn’t changed since 2009 despite a cumulative inflation rate of 35%; rent prices are increasing 12.5% faster than wages; there’s a labor shortage; US billionaires have become 62% richer; many companies have become more profitable while laborers haven’t shared in those profits; and President Biden, like Roosevelt before him, is pro-union.

Is Coffee the Next Big Industry to Unionize?

The coffee industry faces a few challenges on the path to unionzation. Traditionally, unions that receive the most support from their communities support skilled workers, but coffee is perceived as a low-skill job. The whole concept of unskilled labor is, in fact, the verbiage of the larger anti-labor movement. However, that doesn’t change many outsiders’ perception that making coffee is a low-skill job.

Our economy is more service-based than the manufacturing economy that fueled the US 90 years ago. In a manufacturing-based economy, executives had many costs to consider, and labor was just part of the pie; in a service economy, labor is often the biggest-ticket item. Companies are more motivated to stop labor unions in the service industry because they mean higher labor costs in the form of increased wages, steadier hours, bigger teams, and better benefits.

For many industries today, workers have less power than in the 1930s because of automation and globalization. Why pay union workers in Michigan when they can cross the Texas/Mexico border and pay lower wages and no benefits at maquiladoras? The coffee retail industry is not entirely immune to this—while barista positions can’t be exported, we’re beginning to see a rise in automation of brewing, and we could see automation in other areas. Though this technology is still in its infancy, if labor begins to outprice automation at some point, companies looking only at the bottom line will start looking in that direction.

Finally, there’s the question of numbers: Autoworkers were successful in 1936 precisely because they could bring entire plants to a halt, stopping production for whole companies. Today, individual cafés can strike, bringing service at one location to a halt, but consumers can simply go to another coffee shop. In the case of chains like Starbucks, we’ve seen corporate leaders leverage this. Recently, Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz announced that the company would raise wages for all its workers, except those working at unionized stores.

Real power and community support might come from every coffee shop in a city striking, similar to what building service workers in Manhattan’s Garment District did in 1934. When young elevator operator Thomas Young was unjustly fired, operators from over 400 buildings across midtown immediately went on strike for better treatment and union recognition. The buildings were basically inoperable without them, and other garment workers sided with the strikers, refusing to cross the picket line to make clothing. They won union recognition quickly. But the level of cooperation something similar would take in coffee shops city-wide today might be more challenging to achieve and maintain.

The historical power of collective bargaining has given workers some of our most fundamental rights: days off, lunch breaks, worker’s comp, and more. Today we’re seeing a repeat of the economic state that led to union proliferation in the 1930s and 1940s. Whether the rise of unions will also repeat remains to be seen.

Cover photo by Ehimetalor Akhere Unuabona on Unsplash

Valorie Clark is a writer and historian based in Los Angeles. She often writes about coffee, travel, social history, and the intersection of all three. When she’s not writing, she’s probably bending to her cat’s every whim.