In an age where coffee-making can be both a competitive sport and a fully programmable task, some still prefer to pull espresso shots by hand, the old-fashioned way.

In the Berkshire Mountains of Western Massachusetts, No. Six Depot has been roasting and serving coffee for four years, titling their blends after literary references. Every shot of their Notes from the Underground espresso is pulled on their Athena—the classic, hand-hammered, manually assembled machine made by Victoria Arduino since 1905.

Wholesale manager Steven Amash sees the lever machine as a continuation of the artistic culture the shop cultivates. Seasonal visitors are drawn to the region’s arts, music, and dance venues, and the café doubles as a gallery and performance space.

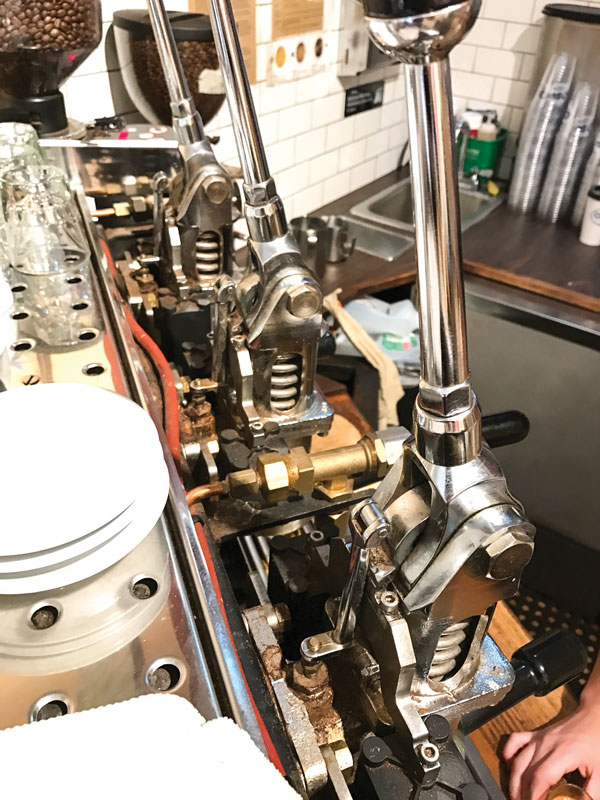

Lever machines evoke feeling. Although there are a few variations, the basics are the same: you pull down a heavy lever, and by releasing the lever, water moves through a bed of coffee grounds to make a beautiful shot of espresso. Although most coffee shops elect to use modern espresso machines—automatic machines where you simply press a button to pull a shot—some opt for an old-school approach to crafting the perfect beverage.

A Work of Art

The Victoria Arduino doesn’t just look good: it also works hard. “We’ve had days where we’re pulling shots one right after the other for eight or nine hours, and we haven’t had any trouble,” Amash says. “The double boiler works perfectly for steaming milk and pulling shots. This thing’s a workhorse.”

In New York City, Oslo Coffee uses La San Marco Leva hand-pulled piston machines in two of its three cafés because they showcase the tactile connection between maker and medium—between barista and coffee.

The machine facilitates that connection rather than controlling it through computerized commands. For Oslo Coffee owner J.D. Merget, “lever espresso machines are the best because they put the barista in touch with the coffee through a real mechanical machine, not just an on/off switch.”

Liz Pasqualo is the manager of Oslo’s Upper East Side Manhattan location. She’s worked with automated espresso machines but prefers the shop’s manual lever, from which the cover panels have been removed to expose the springs and hardware. “If you’re not watching, the shot will keep going,” she says. “It doesn’t stop automatically, so you have to pay a lot of attention,” she says.

One argument in favor of automatic espresso machines is the consistency of output. Still, for Oslo, a staff of baristas tuned into their work delivers a different, no less valuable kind of consistency through attentiveness to drinks and service.

Taste the Craft, Feel the Pressure

Adam Kenderdine owns Benchwarmers Coffee & Donuts, a café-roastery and handmade donut shop in West Reading, Pennsylvania. He praises the quality extracted from his Victoria Arduino Athena Leva 2 Group, which lives on the café counter between a Sonofresco air roaster and piles of donut dough. “Using the same bean, we found that the lever pulls a sweeter, less bitter shot than our old automatic machine,” Kenderdine says.

Lever machines can highlight coffee’s body, mouthfeel, and flavor profile, but the variability between shots might not meet the needs of all cafés. Lever machines bring the excitement—and risk—that each shot of espresso will be slightly different every time.

Oslo barista Dillon Schenker has worked behind the bar for eight years. He’s trained with a timer and scale, calculating the target profile to pull a perfect shot based on measured variables.

“But with the lever machine, there’s none of that. It comes from the hip,” Schenker says. “You don’t have control over those variables in the same way, so you learn to intuit. Not having a safety net personalizes it. The final drink doesn’t get lost in the numbers because a person made it.”

Hands-On Learning

The events coordinator for Brooklyn’s Café Grumpy, Thea Hilburn has worked as a barista, manager, and trainer for over ten years. “The lever machine is perfect for training because it shows the difference between grind sizes. If you’re physically pulling a shot, you can feel it’s too fine because it’s too hard to pull the lever down. If it’s pulling fast, then it’s too coarse.”

It is easy to say that the ideal pressure profile for espresso is nine bars of pressure, but lever equipment demonstrates how nine bars behave. “The physicality of the machine makes the concept easier to understand,” Hilburn says, “especially since coffee shops draw artistic and visually minded people who need to feel it, instead of just hearing the theory.”

Kenderdine has experienced something similar at Benchwarmers. “Everything now is so automatic and scientific that it takes the passion out of espresso,” he says. “Pulling that lever down to pre-infuse the shot, then back up to release the shot—it takes finesse. We chose a lever machine to be more hands-on, raw, and real.”

The lever machine helps define Benchwarmers as a place where things are different. It educates not only staff on the art of espresso preparation but patrons on the process of turning coffee from bean to beverage. “There are not too many lever machines around, so it’s a great talking and teaching tool for our customers and staff,” he notes.

Kenderdine started as a curious home roaster, proving that coffee aficionados sometimes become the next generation of coffee innovators. For this reason, Dutch entrepreneur Wouter Strietman feels home enthusiasts should be brewing with lever-powered espresso machines. He is the founder of Strietman Designs, a company that develops and manufactures lever espresso equipment for home and restaurant kitchens.

“The concept is to make the user part of the espresso extraction, simplifying the technique so that customers see how it works,” Wouter explains of his wall-fixed and countertop models, all of which he designs and builds in his small factory in the Netherlands.

Lever machines restore to espresso the tactile sense that pour-over equipment restored to drip coffee. With a person in charge, they can see, smell, and feel what is happening to yield the result in the cup.

Caspar Strietman, Wouter’s brother, says users “can feel the water, feel the grinds, which is great when you’re talking about different kinds of beans from different countries. It’s all adjustable, and the only electronic element is the thermometer. Making the espresso yourself gives you all the feedback you need.”

Dancing the Dance

Lever espresso machines might not be the best fit for high-volume shops: they are less suited for speed and repeatability of service and can be challenging to operate from an accessibility standpoint. But they can help create a focal point for customers and give baristas a touchpoint for connecting with curious coffee drinkers.

“What I love the most is the physical movements you make,” Hilburn says. “It’s active and dancey, as opposed to pushing buttons or using a paddle to turn equipment on and off.” Working with a lever machine requires choreography, and manipulating a tool through practiced movements becomes the dance that adds art to the bustle of working on bar.

And unlike other automatic tools, lever machines are built to last. At No. Six Depot, Steven has never had to call for equipment servicing. When Oslo Coffee first started serving coffee in 2003—back when the specialty coffee movement was just emerging—their first roasting space was next to a motorcycle repair shop, which heightened their appreciation for tools that stand up to wear and tear.

Schenker remembers, “Six years ago, our lever machine survived a fire in the shop,” he says. “It’s an industrial beast, this badass hunk of metal. There is something cool and respectable about that.”

Photos by Rachel Northrop unless otherwise noted.

This article was originally published on November 8, 2017, and has been updated to reflect Fresh Cup’s current editorial standards.