The Roastery Breakdown series is presented by our partner, Loring.

Carlos de la Torre knew nothing about roasting coffee when he started in 2012. But after winning Mexico’s Cup Tasters Competition—a competition in which coffee professionals taste unmarked sets of coffee to try to identify which one is the outlier—roasting seemed like the logical next step. Plus, he thought it’d help him prepare for the upcoming World Cup Tasters Championship, held later that year in Vienna. “When I won the Cup Taster[s] Championship, I was like, ‘Now I need to start roasting,’” he says.

But de la Torre hadn’t set out to start a business. “It was a need to learn—not like a venture or a start-up idea,” he says. “It just came as a necessity to learn how to taste coffee.” To pay for the roaster, de la Torre began selling small batches of roasted coffee to friends and customers, and using the coffee in his shop, Café Avellaneda, in the Coyoacán neighborhood of Mexico City.

Operations grew organically. In 2017, de la Torre worked with his wife, Yarismeth Barrientos, to develop a brand for his roastery. They decided to call it Café con Jiribilla.

In the meantime, de la Torre has won nearly every coffee competition there is: He’s a multi-time Barista Champion, a Brewers Cup Champion, and won the LA Coffee Masters competition in 2019. When not representing Mexico in international competitions, de la Torre focuses on highlighting coffee grown in the country. Café con Jiribilla only sources coffee from Mexico and seeks to promote the livelihood of all members of the coffee supply chain.

The roastery operates out of a small space, and nearly every coffee is roasted on a machine that can only hold a few pounds at a time. But for de la Torre, these are positive constraints that let his team focus on highlighting the abundance of beautiful coffees coming out of Mexico.

Fast Facts

Roastery location: Mexico City, Mexico

Roasting capacity: 2.5 tons/~5,500 pounds a month, projected to grow soon

Retail and/or wholesale roasting: Both

When To Expand

In the beginning, de la Torre did things mostly on his own.

He started roasting at home on a tabletop machine he called a “Frankenstein,” a Trejo-branded roaster that only had the capacity for five pounds of coffee at a time. “The guy I consulted for the Cup Taster Championship, one of the most renowned roasters in Mexico, gave me my first roasting workshop with this same machine,” de la Torre says. He bought it for less than a thousand dollars.

His first wholesale customer was a restaurant down the street from the cafe. But the turning point for his roastery came when a colleague connected him with Enrique Olvera, owner of the two-Michelin-starred restaurant, Pujol. He began supplying coffee for its cafe concept, Eno.

It was then that de la Torre realized he needed to bring in help—and get out of the house. “I cannot do this alone. I need another roaster,” he remembers thinking. “I need someone to help me. And I started to think about giving the roastery its own space because I used to roast at home in my living room.”

Eventually, the roastery would also get its own name, Café con Jiribilla, to distinguish it from the cafe. “We realized that coffee shops never wanted to buy coffee from us. All of our customers were restaurants,” says de la Torre. “We wanted the coffee shops because they were the ones we thought that can pay the better prices for the single origins and more exotic varieties and not just the house blend for the restaurant.”

De la Torre knew that space would be an issue: The roasting facility he found is across the street from the coffee shop, in a neighborhood “very for tourism and living, but not industry, so we cannot have a super huge roaster,” he says. “[We] realized that we’re going to be a micro roastery, or better called a nano roastery or some sort of super tiny roastery.”

But that constraint ended up serving his roasting business better. “The size was perfect for us because we were buying coffees at very fair or high prices with outstanding quality. And for me, it was kind of dumb to roast those coffees in a huge coffee roaster because I felt that they lost some quality because of the heat application,” he says.

Focusing on small batches also helps de la Torre rotate coffees quickly, and prioritize freshness. He doesn’t have to worry about dozens of bags of one coffee sitting on shelves because the size of the roaster necessitates a larger batch. “We’ve never sold coffee within more than seven days of roasting,” de la Torre says.

Eventually, he added another roaster, a 2.4kg gas roaster, almost doubling the roasting capacity. He’s since added a second 2.4kg electric roaster from Coffee Tech—both are drum roasters, meaning they use conduction energy to roast coffee through a heated drum. De la Torre says the original “Frankenstein” roaster, a fluid bed roaster that uses convection to roast coffee, is mostly there “for the memories.”

He plans on getting a 10kg roaster soon “because this year, we’re growing quite a lot.”

Keeping things small means the roastery’s equipment needs to be working constantly. “One thing I learned about roasting coffee with one of my mentors was that a machine that is so costly, so it needs to be working all week,” says de la Torre. “If you get a super big roaster, it’s going to work just one day a week.” For coffees with highly specific roast profiles, de la Torre will decrease the batch sizes of his roasts to achieve more precision and control.

But de la Torre likes that daily pace—he says it allows the team at Café con Jiribilla to easily track each batch and make changes based on customer requests. “So if one customer wants a different roast, slightly darker, slightly acidic, we can change it and not affect another customer,” he says.

Equipment Breakdown

Small spaces: Café con Jiribilla doesn’t have a big warehouse. It stores coffee and roasts the brand’s espresso blends out of a small facility (that’s where the gas roaster lives), and rents the house next door to use as an office, training space for new baristas, cupping space, and to roast single-origin and competition-level coffees (which are roasted on the Coffee Tech machine).

Because it buys coffee directly from farms in Mexico, it also doesn’t need to hold thousands of pounds of green coffee in backstock. “We don’t have a huge warehouse for roasted coffee, and we just roast on demand,” says de la Torre.

Streamlined tools: He says the small space also allows the team to stay organized without too many systems or tools in place. “In that way, the coffee is always freshly roasted. That gave us the chance to forget about some logistics and focus more on customer service.”

Density matters: De la Torre says the team makes a queue of which coffees to roast on a whiteboard. “We put all the orders there,” he says, although he notes that the queue isn’t based on when an order comes in—instead, he tries to match the roasting schedule to the beans and the temperature fluctuations of the roaster. “[The schedule] doesn’t depend on when the order enters. It depends on how the machine is behaving.”

For example, they might start with lower-density coffee and then move to higher-density beans; within those categories, they then start with washed coffee and move to naturally processed coffees throughout the day. “We go with that order because the machine is getting hotter along the day. So we finish with the harder beans.”

Daily cuppings: Every day, the production team comes together to taste coffees roasted the previous day. Not only is this for quality-control purposes, but it allows employees to share ideas and connect. “It’s not just cupping,” says de la Torre. “It’s also talking about what you did this week, talking about customer issues, and sharing points of view—like changing roasting decisions or making buying decisions together. That’s helped to build a very strong team at Jiribilla.”

Low-fi solutions: Although he bought an industrial-style sealing machine to seal bags of coffee, de la Torre says that, more often than not, the roasting team prefers using a straightening iron. They say it’s “better with the hair thing,” he jokes.

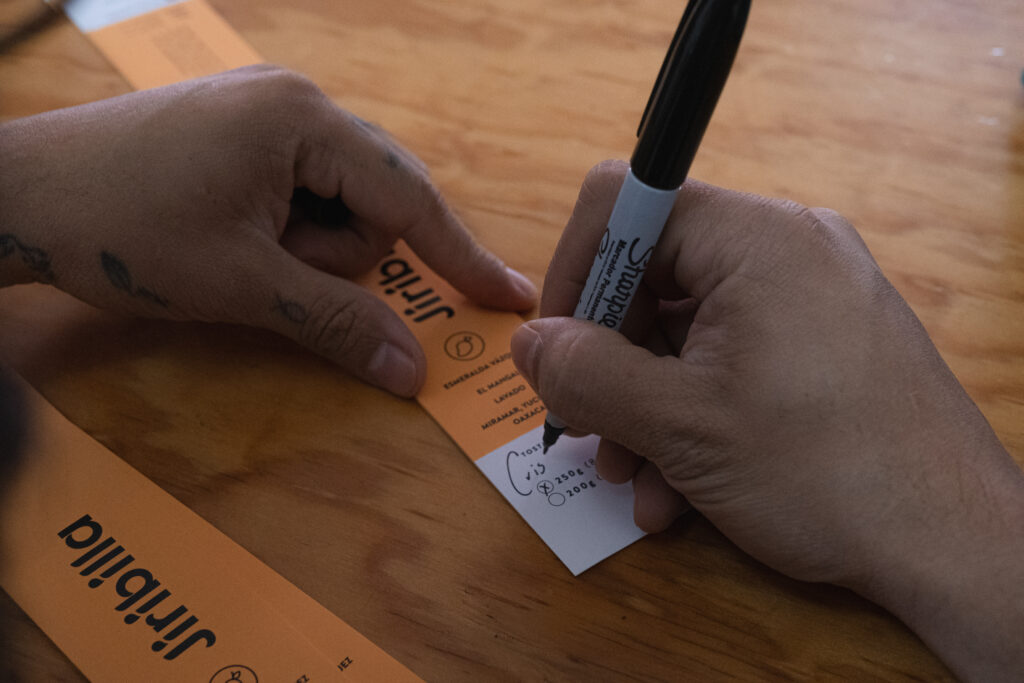

Roasted by…: Each bag of coffee has a space for the roaster to sign their name, so customers know who roasted every batch. There’s also a space to indicate how much coffee is in the bag (either 200 or 250 grams).

De la Torre says that, compared to many other countries, Mexico’s lack of regulations or permits made it easy for him to start roasting in his house, and rely initially on smaller or repurposed pieces of equipment. As he demonstrates, working within the confines of what you already have is a winning strategy—you don’t need a huge roaster or space to get things done.

Working in this small-scale, lo-fi way has also given him the time and space to hone his roastery’s mission. He’s dedicated to sourcing coffee from Mexico because of freshness—he says he can get coffees as soon as a week or two after they’re harvested and dried “ in comparison to the U.S. or Europe or any other country that may get the coffee six or seven months” later. “ So the liveliness of the flavors are different and we understand roasting as a way to preserve the character of the coffee.”

But he also thinks quality involves investment in the entire coffee processing journey.

“ I think you cannot build a concept of quality without getting to know the entire conditions of how a product is made,” de la Torre says. “Quality, for me, is not just about special or exotic flavors. It’s more about consistency […] the only way we can have consistently good coffee is by looking at how it’s grown, how it’s picked, how it’s processed, and trying to find the mechanisms to promote those practices [and make sure they] are consistent too.”