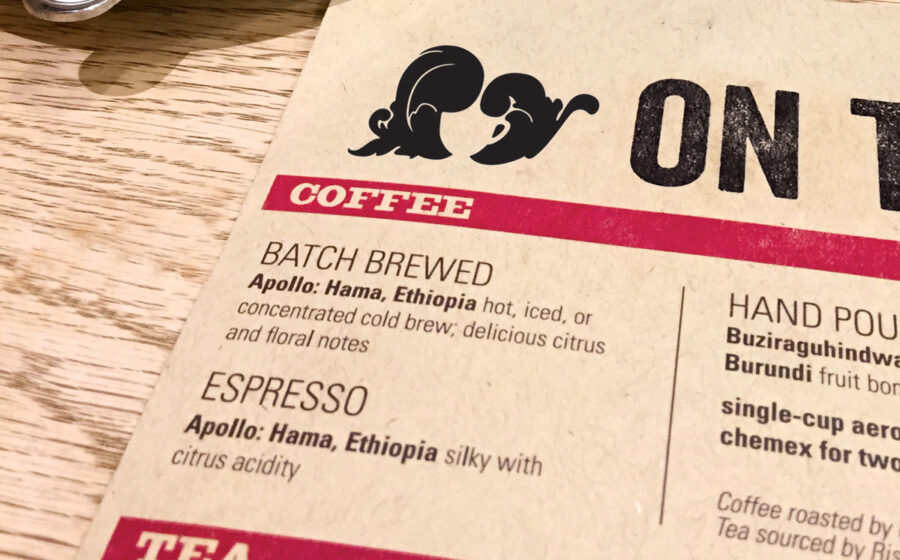

[T]hough in the general coffee world espresso blends are widespread, in the specialty coffee segment of our industry, single-origin espressos are pushing blends off their pedestal. Standard espresso profiles with notes like “dark chocolate, caramelized sugar, and dark cherry” are giving way to lists that often read like a fruit market in the Caribbean: “bright and fruity with notes of pineapple, lime, and bergamot.” Instead of a blend of multiple parts sublimating into a nuanced whole, a single coffee, a single farm, or even a single lot on that farm shines solo as espresso, with all its strengths and weaknesses revealed to the discerning palate.

Wolfie Barn, director of coffee at Pavement Coffeehouse in Boston, points out that the purposes of blends and single-origins are different. “With a blend, the idea is to skillfully mix coffees together to create a uniform flavor profile you can maintain with the seasonal nature of coffee. Single-origins are sold based on what distinguishes them and makes them special.” Another distinguishing factor is traceability: by the very nature of a blend, each farm’s flavor characteristics go toward making something new, more an expression of the roaster’s skill and less directly pointing to the farmers’ abilities. Given the current trend toward direct trade, single-origins allow roasters and baristas alike the chance to highlight their farmer partners in a focused way.

“If done right, natural coffees tend to do well in milk—sometimes they remind me of Fruity Pebbles cereal.”

There are also potential pitfalls to this presentation. Single-origin espressos present a smaller window for error in technique, points out Matt Barahura, café manager at James Coffee Co. in San Diego. “Blends are a little safer—they can be more forgiving of over- or under-extraction,” he says. “I think if you show a command of single-origin espresso it means you are paying attention to your equipment, your extraction, and your knowledge of the coffee and where it tastes good.” Christopher Griffin, co-owner of Stanza Coffee Bar, a duo of multi-roaster cafés based in San Francisco, adds that he likes to use single-origin espresso in training new baristas because it is so easy to taste bad extraction, which trains them to notice those flaws in other preparations.

Espresso can be a strong venue to present a great single-origin coffee, because the concentrated extraction highlights its attributes, emphasizing the lemon acidity and salty tomato notes of a Kenyan or highlighting the balance and chocolate of a good Guatemalan. Still, for customers who enjoy darker, more accessible blends as espresso shots or in milk, single-origins can be challenging. Bridging the gap between customer expectations and more nuanced espresso is an increasing problem in the industry as more and more single-origin coffees find their way into portafilters. A little gentle communication goes a long way, says Lemuel Butler, wholesale representative for Counter Culture Coffee. “You have to take baby steps with folks because we are creatures of habit and change is frightening.” He likes to mention coffees he’s excited about, offer samples, and allow customers their own schedule for experimentation. Barahura agrees. “We have staff meetings to discuss how we present the coffees, the message and tone. We want to make people happy, give them what they want, and not alienate them because coffee is so subjective. I try to encourage people to try things alone first, and then add cream and sugar.”

What about single-origin espresso in milk? This is where the average customer fights back: one doesn’t usually order a sixteen-ounce vanilla latte to have a coffee experience. Butler says, “If done right, natural coffees tend to do well in milk—sometimes they remind me of Fruity Pebbles cereal. I find that single-origin Colombians tend to do well, but not Sumatrans—I don’t want green peppers in my cappuccino!” Barn adds that when he looks for a coffee to use with milk, he targets balanced espressos on the sweeter side, not fruit bombs or highly acidic coffees. A cappuccino made with a natural Yirgacheffe can taste like a blueberry muffin, but that same dominant flavor profile might clash with the vanilla syrup a customer wants to add to a big latte. Many cafés solve this dilemma by using a balanced espresso blend for milky drinks, and offering one or more single-origin espressos for shots, americanos, and cappuccinos.

Though single-origin espressos can disappoint if done badly, with care, lots of attention to detail, and the right dialogue with customers, a barista can present single-origins as a delicious experience worth taking a risk on.

—Emily McIntyre is a regular contributor to Fresh Cup.