[W]hen Michael Rubin was fifteen, he had a pretty good sense that this foster father didn’t really care about him. Yeah, the guy picked Rubin up from the police station where he’d been brought for breaking the ten p.m. curfew, but he was the guy’s responsibility, his problem, so he had to. Many of the other foster families he’d been with in Southern California since his stepmom kicked him out of the house years earlier hadn’t bothered much with him either, though some cared, but he didn’t have anything like feelings for this foster dad. Which to him, at the time, was fine, even normal. He didn’t need this guy to care for him. Even though Rubin wasn’t technically a street kid, at least not for long stretches, he’d developed the intelligence of one. He could scrounge and scavenge, figure out how to make the most of a hard spot.

As they were headed back to the foster house, Rubin said, “There’s a party over there. Drop me off.” A long, long time later, while telling that story over the phone, he says, “And he did it,” with a tone that’s bewildered and disappointed, but not bitter. That moment wasn’t traumatic or life-altering, and there were plenty others that were worse. But it’s illustrative of the circumstances of a childhood that would hold back a run at success but also give Rubin the skills to dig himself out of a midlife hole.

Not many years after that night, Rubin received an inheritance—a farm in the Midwest—and almost overnight turned from not exactly a street kid into not exactly a trust fund kid, but something pretty close. Remarkably, he didn’t blow out his funds the moment he got his hands on them. He scrimped and stretched the windfall. “I think the fact that I knew so intimately what it was like to be homeless and hungry, that is what taught me not to spend the money that was left to me,” he says.

For the next two decades he lived off the rent the farm generated. But while he displayed that fiscal responsibility, it was in the service of what amounted to a long party and a string of jobs. “I worked at construction odd jobs, at a bookstore, on the stock market and investing, in car sales, and they were the bricks that helped me understand that I could have an intelligent and kind conversation with anyone.” While those experiences provided him skills he would later fine tune as a CEO, they didn’t build a career. Eventually he sold the farm, and then, eventually, the money ran out.

When this happened, it was 1991, and Rubin lived with a roommate who owned a coffee shop. One day, the roommate made Rubin a version of the blended iced drink he served at his café. It was made with a cheap blender, just like they had at the shop, and the drink that sloshed out of the pitcher was awful in just about every way it could be. The flavors were wrong and unbalanced. The texture was a combination of thin liquid and jagged chunks of ice. There was as much to chew on as drink.

Rubin had no experience in food but he knew the characteristics he wanted from the drink: cold, icy, creamy, and pourable.

Rubin says that when he was living on the streets he had to develop a keen sense for opportunities. “Life is like a scavenger hunt, and you go out and see niches that others don’t see,” he says. “When other people’s parents took care of everything, they didn’t see the world this way.” That skill had lain half-dormant for two decades, but now Rubin, forty-one years old and staring at a vanishing checking account, needed it again. Standing there in his apartment, holding a glass of something that people paid good money for even though it didn’t deliver what it promised—a blended, cool drink—Rubin saw a niche.

He had no experience in food but he knew the characteristics he wanted from the drink: cold, icy, creamy, and pourable. Icy might seem like a synonym for cold, but it’s about the texture and feeling of a blended drink. A soda may be the same temperature and volume as a slushy, but the latter feels colder and more substantial. His frappe, a name he adopted not yet from the Greek drink but from the Boston-area name (there pronounced frap) for a milkshake, wasn’t a slushy, though. The creaminess would set it apart and allow it to connect flavors, especially coffee, in new ways. Finally, if a barista had to dig every drink out of a pitcher no café owner would buy it, so it had to pour easily.

For the flavors he first developed, he took inspiration from the coffee shops. “My sense of what Cappuccine’s frappe mixes should taste like lived in my imagination. Came from pure instinct,” he says. “I would go into coffeehouses, sit down on a cozy couch, have a latte, a vanilla latte, an Italian soda. . . then just sit back, sniff, watch, and listen, sniff all the aromas floating about as specialty drinks were being prepared.”

For eighteen months he worked on the drink. He would call ingredient suppliers and talk with their food scientists. These experts caught onto the idea fast, intrigued and excited about the puzzle, and Rubin pumped them for information on how to formulate the mixes to get exactly what he wanted. “They don’t know you’re not a million-dollar company,” he says. “So they help.” He tested the formula on his friends and cast mates in the musicals he performed in. He nurtured his frappe, he cared for it, he doted on it like a father.

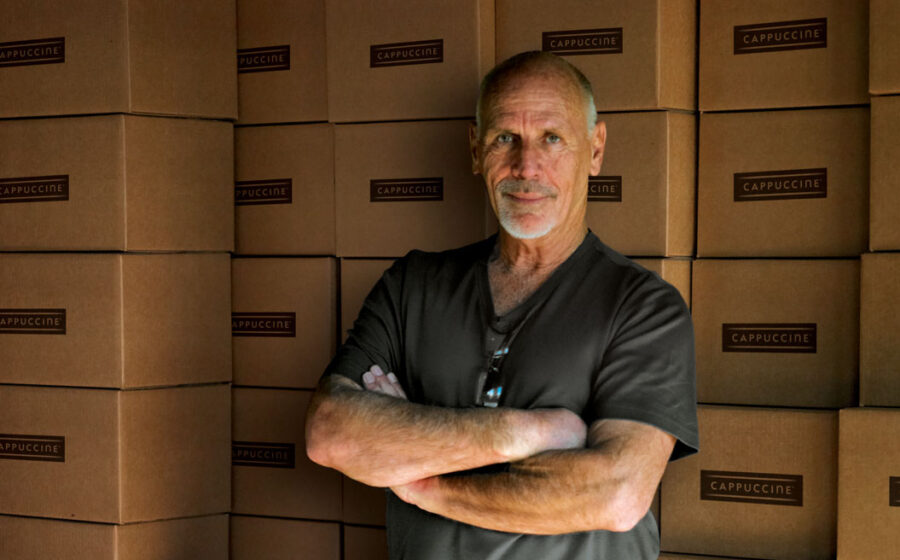

Cappuccine went from a company that needed a boost from an established brand like Vitamix to one that created its own gravity at trade shows.

The formula slowly came together, and in 1992 Rubin took Cappuccine’s first two flavors, mocha and latte, to coffee shops. He knew they would lunge at the new product—but most just didn’t seem to get it. The business got some traction and picked up customers here and there, but mass adoption didn’t happen those first couple of years.

Then, in 1994, Vitamix let him demo Cappuccine at their Coffee Fest Seattle booth. It was a massive venue at a critical moment in the coffee industry. Key players in the industry stopped at the stand to experience the new type of frappe for the first time. Fresh Cup’s founder, Ward Barbee, named Cappuccine best new product at the show. “That’s when the industry noticed us,” says Rubin.

The next year, Starbucks launched the Frappuccino, and pushed the concept into mainstream adoption. Suddenly, independent coffee shops needed a product that could compete with the massive summertime draw offered by the rapidly expanding mega-chain. Cappuccine was there with a full line of mixes to offer.

The ground was set for the young company to experience a massive explosion in growth, but another company came into the frappe game at that moment and threw water on the fuse. Big Train, which remains a powerhouse among frappe companies, released its own set of mixes. The products were and remain similar, but Big Train brought a different sales strategy. “They did direct sales through the telephone,” says Rubin. “We went through distributors, and they made the right choice. They just ate our lunch.”

“We only survived because of the quality of our product.”

I don’t know that there’s anything we can do to get into the third wave. We want to stay true to what we do.

Even with that competition, there was a lot of lunch to be found out there. Starbucks poured money into advertising the Frappuccino, and the market for something cold, icy, creamy, and pourable kept expanding and expanding. Cappuccine went from a company that needed a boost from an established brand like Vitamix to one that created its own gravity at trade shows. Other frappe companies came into the industry, pushing Rubin to adapt his mix, find new flavors, make it better and better. “Every day we do something to improve our product,” he says.

That simple strategy, sticking to quality and fronting the race for new flavors, kept Cappuccine in leading coffee shops and in tranquil financial seas through the nineties and into the new millennium. The second half of the aughts saw a disruption to both those states, and sent Rubin searching for ways to keep Cappuccine vital.

First of the disruptions: the past decade saw the rise of third-wave coffee shops, which almost as a rule don’t have a blender anywhere at the bar. They don’t have packets of mixes. Some don’t even have ice (see: pour-over bars). Fifteen years ago, a new coffee shop owner would have, by default, called a frappe company. Not any more. Very often, when someone who has spent decades in an industry—especially the creator of a product that brought in new customers to that industry—sees that their company and product aren’t part of a new business model, it’s common for that type of person to be dismissive or scornful of the newbies. Rubin’s not, not even a little bit. He knows what his product is, and he loves what it is.

“I don’t know that there’s anything we can do to get into the third wave. We want to stay true to what we do,” he says. Besides, worrying about breaking into a type of coffee shop that is strictly about coffee would take time away from global growth.

The second, much scarier, disruption to Cappuccine’s business was, of course, the Great Recession. “In 2008, when things went down, I took my money out of the bank and began to learn about exporting,” Rubin says. “We wouldn’t have made it if we hadn’t found other markets.”

Over the past seven years, Cappuccine has expanded across the globe, and now international sales represent more than half of the company’s business. Like when they started, Cappuccine’s customers are often small chains and independent shops with customers who want what they’ve found at international chains. “Every time I travel outside the United States, I’m in a time machine,” Rubin says of the experience. “Everything that happened fifteen years ago here is happening now.”

Nearly twenty-five years ago, Rubin was formulating new flavors, creating a new drink for cafés. That’s happening now, too. He’s getting ready to launch an organic vanilla latte frappe, and he loves it. He says, “It’s like being a daddy again.”

—Cory Eldridge is Fresh Cup’s editor.