Marianella Baez Jost grew up in Costa Rica “not knowing anything about coffee,” she says. She met her husband after attending the University of Nebraska for college, after which the pair moved to Florida. Craving a new challenge, they decided to buy a coffee farm, Café Con Amor, in 2013, so they could “start learning from the ground up, literally.” Since then, Baez Jost has taken it upon herself to “follow the beans from the moment of planting to the final product enjoyed in coffee shops around the world.”

This journey led her to found Farmers Project, a direct-trade relationship platform. It also fueled her advocacy for coffee farmers at large, many of whom struggle to meet the cost of production, never mind make a living (or a thriving) income. She realized that farmers alone cannot shoulder responsibility both for regenerating the land and maintaining the “great-quality coffee for cheap prices” that specialty consumers have come to expect. That’s all the more true because consuming countries have played an outsized role in the climate change-driven weather events and coffee diseases that affect farmers’ harvests and livelihoods.

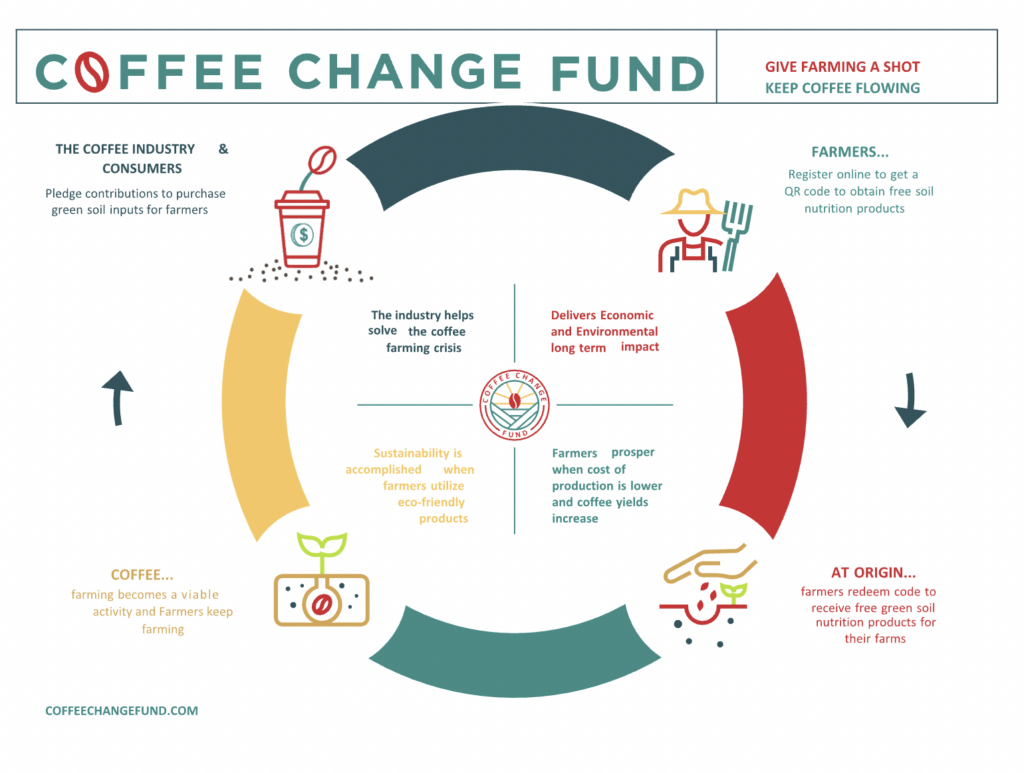

More recently, Baez Jost started the Coffee Change Fund, an open-source idea that she envisions as a traceable, consumer-driven funding mechanism that provides farmers with free, locally available green soil inputs like green fertilizer or biochar. Baez Jost is looking to fund the project, which, once implemented, would give conscious consumers a way to bypass sustainability claims made by roasters and reach farmers directly via a transparent, digital platform.

Baez Jost has long used social media as a tool for her advocacy. With recent attention being paid to coffee pricing and how factors like tariffs and weather patterns will affect consumers, she has doubled down on her efforts to refocus the narrative. Sure, consumers may have to pay more for coffee—but this moment also reflects a decades-long crisis for producers who simply can’t make ends meet.

In this interview, Baez Jost cuts through the “crisis” talk to share her ideas about how to keep coffee viable, including why $4 per pound should be its new entry-level price. She also dreams of forming a Specialty Coffee Producers Association to ensure representation of producers by producers.

Despite the many possible routes towards a more just and sustainable coffee industry, Baez Jost believes in platforms like Coffee Change Fund, which create direct connections between farmers and consumers. “It allows consumers to put their money where their mouth is, invest in the farmers, and invest back into the planet that we’re trying to save,” she says.

The Coffee Change Fund website describes the platform as a way for “everyone in the industry to become the solution” to issues like pricing concerns and climate change. Why do we need to get more stakeholders involved?

We ask too much of producers already, and it’s unfair of the market to ask producers to solve the environmental chaos that we’re in. If we want regenerative coffee, then we need to invest in the soil, not just extract.

That’s why my idea is going to those conscious consumers who say, “I’m the one who drinks the coffee. If there’s a traceable, digital, trustworthy system, I want to put my little bit of effort into the ground, I want to help farmers farm on my behalf.”

What are your main frustrations with how we talk about the “coffee pricing crisis” and other issues plaguing coffee?

Everybody’s talking about price increases at the point of sale as a crisis. But the truth is, we should start from the point of production: If we don’t look at the real cost of coffee, we’re not gonna have coffee for too long. We’re having farmers abandon their farm. We’re having pickers decide to do something else that’s more lucrative, or to immigrate.

Farmers have been in crisis for decades. We’re having rains during harvest, when we’re supposed to have sunny days to harvest our beautiful coffee, or we’re having droughts during the flowering so the flowers don’t take, and we end up with less yield. All of that has compounded to the point that it’s affecting supply and demand. Now everybody’s freaking out because you can’t find good coffee under $5/pound when, a year ago, you were finding it at $2.50.

I think it’s time for everybody to raise the bar. We need to understand that this is not just the typical ups and downs of the market. This is now pushed and pulled by climate change. It was already hard to produce coffee, but now it’s extremely hard to produce coffee.

You recently made a post on LinkedIn comparing egg and coffee prices. As you pointed out, they’re both things we consume for breakfast and that we assume we will always have access to. What motivated you to make this comparison?

I was thinking about how unfair it is that everybody makes coffee price increases a huge deal. Our customers, the roasters, are like, “How do I explain this to the consumer?” And I’m thinking, “Do you really explain to your consumers when eggs or oat milk or bread goes up?”

Ten years ago, you could buy bread for $2, and now whole-wheat bread is $6. Why do we have to almost beg people to value their cup of coffee? Do you question your bartender when your glass of wine is now $14 instead of $10, or when your craft beer is $7 when it used to be $4? The reality is that coffee is a handmade product that has been underpriced for too long.

You’ve written about how a $4 per pound price for coffee could be a new benchmark for the industry. Tell us more.

The majority of coffee farmers are smallholders with five acres or less of land, and there are a million variables that go into the cost of producing coffee. In specialty, I don’t know anybody who is doing right by the soil who can produce very good quality for under $2.75 per pound. That’s before the wet mill, where you add another $.40 per pound, and the dry mill, where you add another $.25 per pound, before you get to FOB [free on board, or the price an exporter pays for coffee, which usually includes cost for processing and transport along with the price a farmer gets for their product].

Ultimately, if I’m getting less than $4 per pound, there’s no incentive for me to export my coffee. I’m not even talking about doing honeys or any kind of [experimental] fermentation, which adds 18 days of more processing at the wet mill and more resting time for the coffee. If the other country is not willing to pay my costs plus a little [profit] margin, I might as well just sell it in-country to a co-op that’s gonna pay me less.

Some people say the C-market price will [decrease again], but I’m hopeful that it will cause a deeper gap between the C-market and specialty, which means specialty will be better valued. $4 per pound should be the entry level of exporting coffee, and I hope it becomes the new normal.

How can specialty reconcile this conflict between image and action—what people say about compensating farmers fairly versus the reality?

I think consumers are in a bad position because right now, we’re bombarded with claims about how everything from our phones to our sneakers are saving the world. I don’t think it’ll ever be black-and-white, because greenwashing gets in between. Many coffee consumers are trying to do better, but they don’t realize that their coffee was more than likely bought at commodity prices, without traceability, and not as fresh as they think.

But there are small and medium roasters who have invested everything they have into educating conscious consumers who know what’s behind that cup, that the land and the people at the farm level were treated with respect.

My goal with the Coffee Change Fund is to shift the way conscious consumers can reach the farmers. It’s anchored on bypassing greenwashing and corruption. Because that’s where my frustration always ended up. It’s like, ‘How do I get people to understand that paying more is not necessarily the right thing?’ Because that money is not landing at the level of the farmer, land, or planet.

You’ve also proposed starting a Specialty Coffee Producers Association. How would that support producers?

A producers-only association would focus on sharing what prices we are getting as producers. Because of colonialism, the foundation of coffee information only flows to the buyers, and we don’t know the layers or what producers end up with.

When you’re a small producer, the co-op dictates your price. The receiving stations literally put a piece of paper that says, [for example], “$1.30 per pound” in Costa Rican colones—that’s what I’m paying you right now. Even with the market hitting $4 per pound, the co-ops give you an advance at the beginning of the harvest […] That advance could be $2—it’s not even the C-market price. And what they pay you at the end of harvest hinges on their own commitments to big buyers. They negotiate the best they can, but they don’t give you the money until they figure out how well they did.

The goal of an association would be to have regional chapters that aggregate data about the selling price that farmers pocket on a regular basis. For example, I sold at $4.05 this week, the next week I saw $4.25. When the rain comes, we have to rescue what we can by giving the damaged coffee to the co-op.

If we get farmers in other countries to do it too, then we have a parallel market to the C-market—we can say, “Just look at what producers in Brazil, in Ethiopia, are saying.”

The C-market can go up and down, but we can say, “Nobody’s selling under $3.50.” Then we […] become price setters, not price takers, who can be confident about the value of our product. Now, people are used to taking whatever the price is. And that’s bullshit [laughs].

Do you think the members of a Specialty Coffee Producers Association would be afraid of the reaction from the co-ops who have set prices for so long?

Yes, I think that would be one of the biggest barriers. Most people are fearful that their buyers, even if they’re abusive, will retaliate and say, “If you’re setting the price, we’re not buying.” Co-ops play a role almost like a credit card—they lend producers money and allow them to get [things like] fertilizers ahead of time. But everything is charged against that harvest. So producers would be very scared that if the co-op won’t give me inputs, I’m gonna be outta business.

Producing coffee is competitive, kind of like playing a sport. People don’t want to share their cost of production. They would be ashamed to hear that they’re doing it too cheaply or that it’s more expensive than it should be. But the lack of communication is really hurting farmers—we don’t work as a team, even within one country.

Let’s end with a recent win for your farm. Yaggy Road Roasting Co. in Indiana just released a single-origin canned cold brew with coffee from Café Con Amor. How did that come about?

About six years back, Ben of Yaggy Road contacted me from a college dorm to buy some coffee. He asked for 10 pounds, but our bags are 152 pounds [laughs]. Not even two months later, he calls me back to say, “I can already buy one sack!”

He also said he wanted to donate to one of our campaigns from Instagram. At the time, I knew a farm worker, Abel, who needed to rebuild his casita due to rain damage, and we were helping him buy the cinder blocks. Both Abel and Ben were 24 years old. So I figured Ben would donate 20 bucks, but he sent me a check for $240 in January 2019. I thought it was a mistake, but he said no.

Now, I carry three things in my planner: One, the Virgin Mary—I’m a big fan—two, a list of my goals, and three, the check from Ben. Through him, I realized one good person can make a huge difference. So when he and Walker, Ben’s college roommate, decided to do their first cold brew, they reached out again because I was the first person that they created a direct relationship with. It’s been true mutual inspiration.