Making coffee means making waste. At nearly every stage along the way from field to cup, byproducts are created.

There’s pulp or husks and often wastewater at farms and processing facilities. Roasteries finish the day with piles of chaff and jute bags. And baristas fill knockout tubs with hundreds of espresso pucks a day. This amount of byproduct isn’t unique to coffee—just check out the garbage bins behind any restaurant.

Plenty of roasters and coffeehouses define themselves by earth-friendly practices; as a whole, the specialty coffee industry is green-minded. But not every café has a municipal composting system at hand, and not every roaster lives by farmers in need of jute bags. So what options are out there? What can be done to make coffee processing friendlier to the exceptionally fragile areas where the beans grow?

There are a lot of solutions (gardeners provide many). Some can lower coffee farmers’ production costs, and a few may someday bring a new cash stream for cafés. One even grows food.

Pulp and Husks

After picking, coffee cherries lose about eighty percent of their weight when the meat gets pulled off in a pulping machine. Finding a use for most of the mass hauled in from harvest has become something of a global mission.

Researchers have tried to turn pulp into livestock feed for decades, especially in Africa. There’s so much energy just sitting there, but the pulp’s high levels of tannins and caffeine stymie project after project. Pulp can be mixed with other silage, though the tannins and caffeine remain problematic. Discouragingly, the processes to decaffeinate the pulp often make it unaffordable as feed.

If animals can’t handle much pulp, humans can. Well, we can eat mushrooms grown out of it, at least. In many coffee-growing regions, the pulp is pasteurized, dried, mixed with spores, and packed into plastic bags. A few weeks later, a bloom of oyster, shitake, or other domestic mushrooms can be harvested.

The options are more limited for coffee husks, the remains of the cherry after dry processing. Traditionally, husks become cascara, often called coffee cherry tea. In Uganda, the world’s largest cement maker, Lafarge, uses coffee husks to fire its kilns. It’s not exactly a green victory, but it cut the factory’s fossil fuel consumption by forty-five percent.

Wastewater

The wet processing or washed method produces a tremendous amount of water infused with organic matter. Often, it’s discharged into water sources used for drinking water, which directly threatens human health. The untreated wastewater also creates methane, a greenhouse gas significantly worse than carbon dioxide.

The methane, though, points to a solution.

In 2010, UTZ Certified, an international certification program focused on sustainable farming, launched a water-management project called Energy from Coffee Waste. The project runs in several Central American countries and seeks to treat coffee wastewater and turn it into energy. Methane generated by the wastewater is captured in the treatment systems, providing biogas for production facilities to run pulping machines and for farmers to heat kitchen stoves and other appliances.

The program includes nineteen production facilities, some operated by large companies and others run by farmer co-ops.

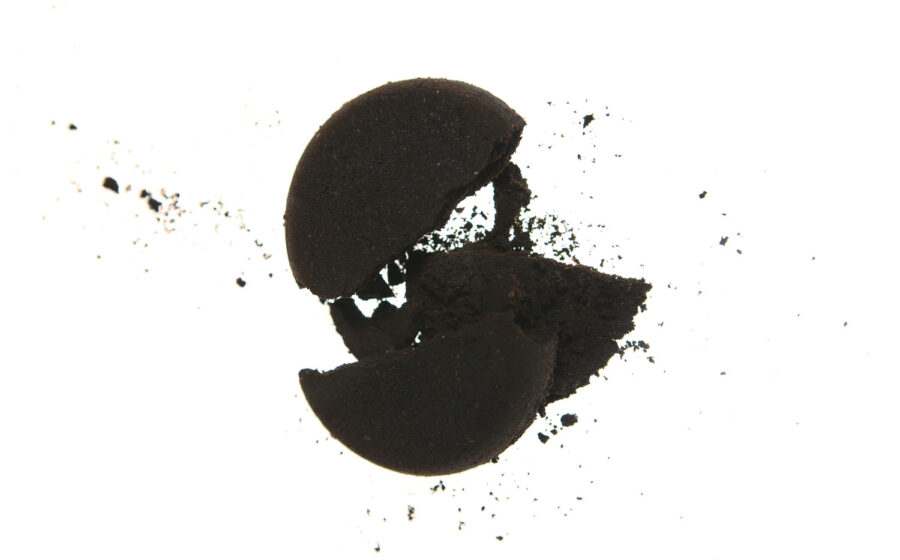

Grounds

Does it even need to be said that grounds make great compost?

Broadcasting that knowledge isn’t the issue for most coffeehouses. The problem is finding enough takers for the pounds generated daily. Not every café runs in a city with a composting program or sits in a restaurant-heavy zone frequented by commercial composters. Grounds giveaway schemes can get complicated fast, so the mind-numbing simplicity of Kobos Coffee’s solution stands out. “A barista came up with the idea to make a bin and put a ‘free’ sign on it,” says Kevin Dibble, Kobos’ production manager. “As soon as we drop a full bag off, it’s gone in ten minutes.”

While neighborhood gardeners may remain the primary beneficiaries, the past couple of years has seen an uptick in new uses for grounds. You can thank science.

In 2012, scientists from the University of Navarra in Spain found that grounds retain much of their goodness after brewing. With some processing, the grounds could be a profitable source of antioxidants for supplement makers, unless they’re brewed in a Moka coffeemaker.

Late last year, Portuguese scientists distilled alcohol from coffee grounds. A tasting panel said the resulting hooch wasn’t too palatable, but with an oak barrel (maybe one that aged coffee beans) to mellow it, this could lead to a next-level Spanish coffee.

While antioxidants and booze are great uses for grounds, those processes still need a champion to scale up production.

Another chemical trick, turning spent grounds into biofuel, may become a big business in London. Oils make up ten to twenty percent of grounds. Last year, scientists at the University of Cincinnati announced they had extracted the oils, turned the dried grounds into activated carbon (the stuff that filters water), and filtered the oil through the carbon to make biodiesel.

In London, a company called Bio-bean will use a similar process to make bio-diesel. Instead of turning the desiccated grounds into carbon, Bio-bean will make bio-mass pellets to fire broilers. They plan to collect grounds from mass-market coffee producers around London, but maybe someday, a coffeehouse can exchange a bucket of grounds for a gallon of gas.

Jute Bags

The only non-coffee-based byproduct on our list, jute bags are the most versatile of the waste made along coffee’s path to the cup.

Everyone from potato farmers to paper makers to gardeners to furniture artisans to handbag designers clamor for these bags. Jettisoning jute bags requires only a Craigslist ad.

Among customers, gardeners are once again good recipients of the bags. Andrew Barton, a hobbyist gardener, lays jute bags between his vegetable rows. “They’re very tidy,” he says. “It’s like making a floor,” and the floor keeps weeds at bay. Jute is a plant fiber, grown mostly in Bangladesh, so the bags are biodegradable but tough.” Barton says the bags he set down a year ago are still holding up.

Kona Paper closes the jute bag loop neatly by making paper from jute bags that can be used for menus, coasters, or cup sleeves. The Baker family at I Know Hope turns coffee bags into a whole line of purses, larger totes, and even wallets and journals. Independent craft stores often sell jute bags, and a free supply would be a windfall. For roasteries in agricultural communities, a few calls to farmers could dispose of a pick-up truck worth of burlap. What farmer couldn’t use more burly bags?

Chaff

Of all the byproducts, the most obnoxious must be chaff. The silver skin that flakes off beans and gets sucked out of the roaster becomes a lightweight yet voluminous and static-charged mess. Roasters used to burn the stuff, probably out of spite more than for disposal.

Handling chaff often discourages roasters from finding a solution beyond the trash. But there is a group who wants it: farmers and gardeners.

At Equal Exchange in Massachusetts, several farmers haul away 600-840 cubic feet of the roastery’s chaff a month. Because the roastery uses only organic beans, the chaff is perfect for the area’s organic farms. After farmer Eva Sommaripa delivers her herbs and edible flowers to Boston’s top kitchens, she picks up the pillowy bags of chaff. The chaff dries and bulks up compost at her South Coast farm, Eva’s Garden, making it easier to spread.

On a smaller scale, Jenny Bush, a horticultural therapist at Trillium Family Services in Portland, will soon take chaff from Kobos Coffee to use in her therapeutic garden and flowerbeds. “It’s got nitrogen and other elements that fast-growing plants can use,” Bush says.

A less explored use for chaff, but one growing in potential, is as bedding in chicken coops. In cities with accommodating livestock laws (which are increasing in number), chickens appear in more and more backyards.

A few years ago, author and backyard chicken keeper Lyanda Lynn Haupt received a bag of chaff and replaced the wood shavings in her coop. “Like cats, they can be unnerved by novelty, and I wasn’t sure what they would think of their new chaffy home,” she wrote for Mother Earth News. “But they all immediately ran into the coop and started ‘playing’ in the chaff, tossing it up with their bills.” Many of the same people who want grounds for garden composting raise chickens. Maybe they’ll take two or three byproducts off your hands.

This article was originally published on March 16, 2014 and has been updated to meet Fresh Cup’s current editorial standards.