Consider your cup of coffee—or rather, consider the three billion cups of coffee consumed each day, according to the International Coffee Organization (ICO)’s 2022–2023 Coffee Development Report. While previous ICO reports—the first was published in 2019—have explored topics related to the sustainability and resilience of coffee, the most recent is the first to focus on creating a circular economy in the coffee sector.

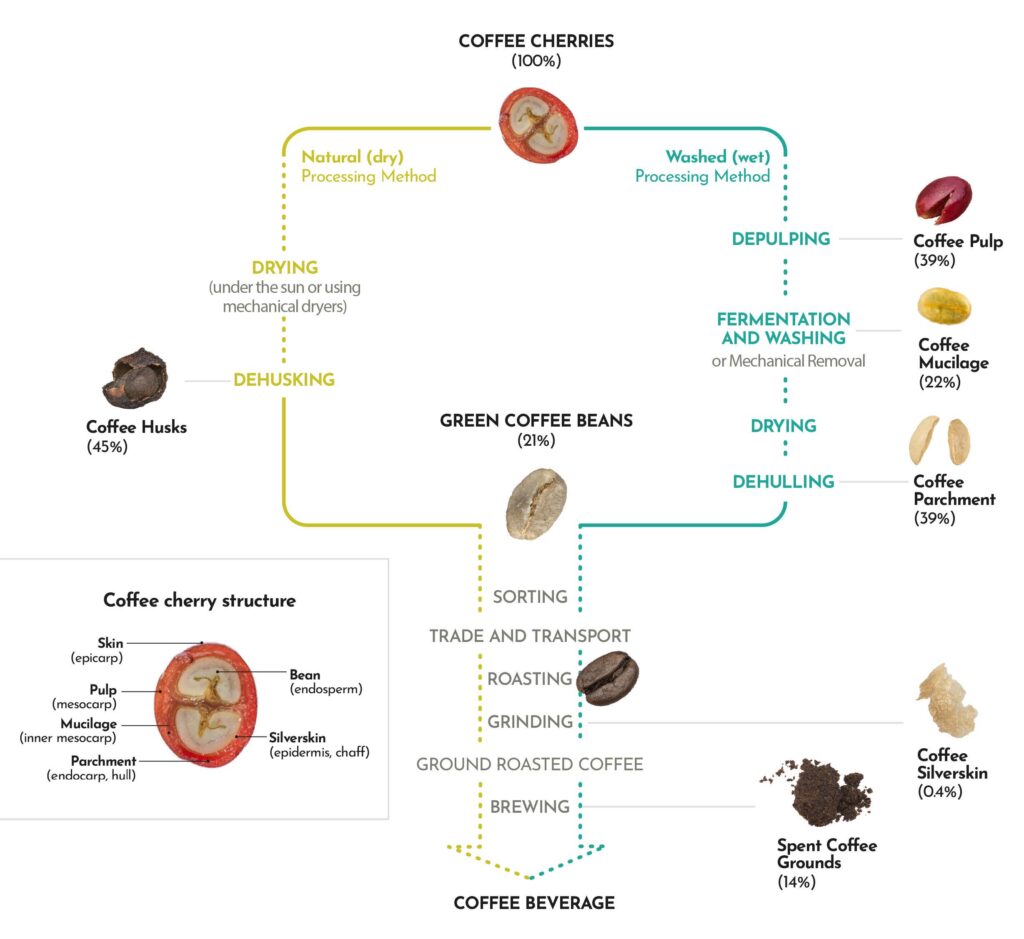

A circular economy is driven by principles that optimize resource use and minimize waste in order to create value. To this end, the ICO report outlines both existing challenges gleaned from stakeholder surveys and policy recommendations to support circular practices in coffee. It starts by quantifying the amount of coffee biomass created globally. For example, you may be surprised to know that only 1–5% of the original coffee fruit ends up in your drink, while the remainder—including pulp, parchment, silverskin, and spent coffee grounds left after brewing—typically becomes waste.

When most people think of coffee, they think of beans. Yet beans are just a part of the whole; in fact, they are only the seed of the coffee cherry. And while the coffee bean is typically the most valuable part of the coffee fruit, it’s a big investment: One metric tonne (equivalent to 2,205 lbs) of coffee cherries yields just 200 kilograms (441 lbs) of green coffee.

Some companies try to reduce post-consumer waste by upcycling or composting packaging and spent coffee grounds (which constitute 14% of coffee waste by weight, alone). But we shouldn’t forget coffee cherries—an early, less-visible byproduct of coffee production, often referred to in dry form as cascara.

Though coffee cherries are regularly classed as waste today, change is on the horizon—at least if the movement towards circularity in coffee has any say in it.

Seeing the Coffee Fruit for the Beans

To understand how coffee waste can contribute to a circular economy, we have to understand just how much of the coffee cherry is potentially reusable—a major goal of the ICO report.

The coffee processing method determines how the cherry is treated, and therefore how much byproduct there is to use. Natural coffees involve sun-drying the coffee fruit, in which case the husk—which makes up about 45% of the coffee cherry by weight—is then dehulled from the green bean. Washed coffees, by contrast, create pulp (the coffee fruit attached to skin) and mucilage; after fermentation, any mucilage remaining on the bean is washed off or mechanically removed. In this case, the pulp accounts for 39% of the cherry and the mucilage 22% by weight. (Coffee parchment and green beans make up the remaining percentages).

The Center for Circular Economy in Coffee (C4CEC), a key partner in the creation of the ICO report, understands the untapped potential of the coffee cherry. Based in Turin, Italy, C4CEC was founded by the Lavazza Group in partnership with the Politecnico di Torino and the University of Gastronomic Sciences, among other partners. It describes itself as the first global platform that aims “to accelerate the transition to a circular economy in the coffee sector and to shorten the learning curve for those looking to transform coffee waste into valuable resources,” as C4CEC project development and operations consultant Mariamawit Solomon Kassa writes in an email.

C4CEC created a “Good Practices” database with use cases for how coffee—the plant, cherry, its component parts, and other byproducts like spent coffee grounds and packaging—can be reused across the value chain, in both producing and consuming countries. Users can, for example, look up jute bags and find ways that they are already being reused.

But the biggest barrier to creating a more circular economy for coffee is our collective “economic-cultural” hesitation to see waste as potential new products, writes Dario Toso, C4CEC’s head of the scientific board, in an email. We also tend to focus on recycling materials post-use instead of looking for ways to reduce or reuse waste at various stages of production and consumption.

“One common misconception about circularity in coffee is that it solely involves recycling,” says Toso. “While recycling is a key component, circularity is a more holistic approach that looks at the whole life-cycle process, from raw material to end-of-life.” He says the C4CEC team is continuously adding new use cases in hopes it can move the needle on circularity; for example, it notes that cascara husks can be processed into briquettes and used as an alternative energy source at origin.

But due to the risk of contamination, processing cascara properly is key, says Dr. Macarena San Martín Ruiz, lecturer and deputy head of the Bachelor of Science in Energy and Environmental Systems Engineering program at HSLU in Switzerland. When farmers don’t move to process it quickly, “it’s highly perishable and can quickly become a source of environmental pollution,” both when piled up on farmland and when it leaks into rivers, she says.

The last couple decades have seen co-ops and multinationals making investments into the infrastructure needed to process cascara for export. However, says Toso, further development is held up by the “misunderstanding that circular practices are prohibitively expensive or technologically complex. In reality, there are numerous simple, cost-effective solutions that can be highly effective.” For example, converting coffee production waste into organic pesticides, fertilizer, and biochar at origin can yield environmental and economic benefits, like minimizing emissions, reducing farmers’ costs, and promoting soil health.

Dr. San Martín Ruiz conducted her PhD research on sustainable management of coffee byproducts at CoopeTarrazú R.L., Costa Rica’s largest coffee cooperative, where farmers reuse coffee cherries in fertilizer and mulch. However, her research showed that improperly treated cascara emits significant amounts of the greenhouse gas methane, and cannot simply be applied to soil without processing.

“Cascara is full of promise, but it’s not plug-and-play,” she says. “Drying must be done under hygienic conditions, and many end products need to pass food safety tests to comply with national regulations. That’s not always feasible for smallholder farmers working solo. But in cooperatives or with supply chain partners, it becomes much more viable.”

Value Hidden in Plain Sight

Though it can’t solve the waste problem alone, the food and beverage category offers some of the most visible ways to reuse coffee cherry byproducts. Coffee cherry tea has long been consumed from Ethiopia and Yemen to Honduras, which creates a precedent for the wider culinary use of coffee cherries in products like cascara flour and ready-to-drink (RTD) beverages.

Some companies have even made a soluble cascara powder, which is “a standardized extract of dried cascara, measured for moisture, color, polyphenol content, aroma, taste, and food safety,” says Siva Subramanian, senior vice president and global head of coffee innovation at ofi, a global food ingredient supplier. (ofi’s product verticals include coffee, cocoa, dairy, nuts, and spices, and it sources coffee cherries from its own coffee estates.)

The soluble powder form makes it easier for manufacturers to reuse cascara. “We believe we have solved the challenges of standardizing soluble cascara, which opens up a lot of opportunities in food and beverage applications,” says Subramanian. “The scale is small, but with consumer interest in energy and functional beverages, consumption is slowly increasing.” According to Subramanian, for every kilogram (2.2 lbs) of soluble cascara, 10 kg (22 lbs) of coffee fruit is upcycled; ofi has upcycled ~10,000 kg (22,046 lbs) of coffee fruit so far.

Ultimately, food and beverage is just the tip of the iceberg. There’s a lot of potential to create value with coffee byproducts directly on coffee farms, says Dr. San Martín Ruiz, and farmers with the right infrastructure can also produce commercial products for sale or export.

“In some cooperatives in Costa Rica, farmers produce cascara flour, hand sanitizer, animal feed, cosmetics, and a range of drinks,” she says. “But tapping into these markets requires care and precision,” alongside supply chain partnerships that support logistics and transport.

At this early stage, efforts to reuse coffee byproducts can feel scattered. C4CEC believes its work highlighting the many ways coffee products can be reused will help to “share knowledge, reduce duplication, and build a more integrated, resilient value chain,” says Mariamawit.

“No single organization can tackle the full spectrum of opportunities in coffee waste transformation alone and frankly, we don’t have the luxury of time,” she says. “There are countless avenues for creating value. But developing each one in isolation would take years. […] By working together across companies, sectors, and regions, we can move faster and further.”

Putting the Coffee Cherry to Good Use

Without a market for the enormous supply of cherries, farmers often put them in piles that can ferment, attract flies, and ultimately contaminate water sources, says Dr. San Martín Ruiz. “But they don’t have to be wasted. When managed properly, they become valuable tools.”

Ultimately, Toso of C4CEC says, the most successful reuse solutions can be scaled up—made bigger and applied across different regions—and this depends on factors like technological feasibility and regional regulations. The Zero Waste Coffee Project has highlighted various efforts to upcycle coffee cherries, such as using them as an alternative to pectin, employing them as the base for an imitation leather textile, and even making them a functional ingredient in cosmetics. Though it’s unlikely we’ll find ourselves wearing cascara “leather” shoes tomorrow, consumer adoption is also key to implementing such changes.

Hacienda Sonora, a 100-hectare farm in Costa Rica, started processing cascara at its own dry mill around 2005, according to general manager Diego Guardia. The farm sells cascara via Sucafina, which can be found via roasters in Denmark, the Czech Republic, and Ireland, among others. But Guardia says “the market for cascara infusions seems already capped.”

Instead, he thinks coffee cherries have potential as an essential food ingredient. “To help farmers around the world, we would need a big industry to use cascara to create” food items to feed people, he says. “The day that happens, we will see big facilities in every mill to clean and dry cascara in an efficient manner.”

Consider your cup of coffee once more. Keeping coffee financially sustainable for farmers will require us to use the whole coffee fruit. “Climate change and the urgent need for living incomes demand action now,” Mariamawit says.