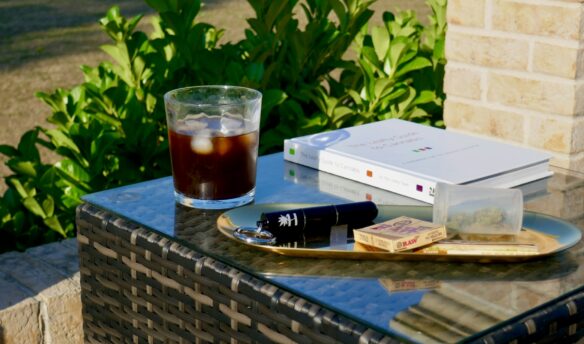

I was sent home from work on March 13th, 2020. Though the once-whispered worries of COVID-19 had become a roar amongst my coworkers by that time, I didn’t know what the afternoon—or the future—would bring. That morning in 2020, I drank coffee and wrote my morning pages at G&B Coffee in Grand Central Market, a peaceful habit I’d picked up while working in chaotic downtown LA. I didn’t know it would be the last time I drank coffee in a café for a year.

As businesses shut down, I felt I had to scramble to mitigate the damage. At Go Fund Bean—a nonprofit organization I helped start with my coffee colleagues, was born out of that scramble—we began compiling virtual tip jars to raise money for hourly coffee workers sent home for what we thought would be just a short period of time. The economic toll on baristas being laid off en masse was evident and immediate, but I also thought about my own experiences behind the bar. In particular, I thought about this one shop I managed that was popular and did well, but like most shops, our financial security was always precarious. I worried that coffee shops would last even a few weeks without customers. When margins are razor thin, any disruption can spell disaster.

Coffee shops, which rely heavily on in-person business, hemorrhaged money during those initial closures. While other industries could adapt by transitioning to remote work, serving food and beverages does not easily translate to an online business model. Though outdoor and to-go service became options, these modifications weren’t perfect solutions: some shops didn’t have the space to set up outdoor seating areas, many were in areas where inclement weather could decimate customer foot traffic, and most shops couldn’t replicate the same volume of business needed to stay afloat.

For some, the temporary closures in March became permanent closures, and the losses are still felt by their communities. The United States lost about 330,000 businesses during the first few months of COVID, well above the expected business closure rate. These closures account for over a million permanently lost jobs. While not all those businesses were food and beverage, many lost at least one special gathering place. COVID was a psychological crisis as much as it was an epidemiological crisis; the grief over beloved cafes, community spaces, and even lifestyles lost is ongoing.

Partially Closed

After shutting down in March 2020, Casey Gleason and her sister and partner Joey decided to permanently close the cafe portion of Marigold Coffee in June 2020. The café had once been a fixture of the community, but to save the roasting arm of the business, Gleason decided it was best to keep the doors closed, and the cafe never reopened.

“It was an excruciating decision,” says Gleason. Joey started Marigold Coffee in Portland in 2009, and Casey joined the business a few years later. Together, they decided closure was the safest way forward. “There was too much uncertainty, and the profit margin for cafes is so razor thin,” Gleason explained. They had to lay off their retail employees but stayed in touch and helped them navigate the unemployment system.

COVID was a psychological crisis as much as it was an epidemiological crisis; the grief over beloved cafes, community spaces, and even lifestyles lost is ongoing.

The decision to close the café was painful but necessary to protect the roasting part of their business. “We wanted to acknowledge to our staff this isn’t something that we can just muscle through without suffering long-term damage.”

Today, Marigold is still recovering from the strain of COVID-19, financially and emotionally. “We moved to a four-day work week because everyone is so exhausted. We changed our pay structure so people could still afford to live.” Gleason shared that many other businesses are going through the same troubles: “I saw a lot of my peers in the coffee industry just go through hell,” Gleason says.

Many businesses have shuttered permanently, and those left standing are still dealing with an industry that has yet to fully bounce back. Customers are still spending less, meaning businesses are still struggling. But more than anything, Gleason is tired. Gleason mentioned that she knows “a lot of owners and senior staff who are just fried.” Referring to the mass exodus of exhausted healthcare workers, Gleason believes we’ll start seeing similar resignation patterns in food and beverage.

Continuing After Closing

In Marigold’s old space is Portland Cà Phê, a cafe and roastery that specializes in sourcing coffees from the central highlands of Vietnam. Customers still patronize both businesses, ordering beans from Marigold online and attending pop-ups while visiting Cà Phê for the full café experience. “The community has been very warm,” Gleason said.

These transitions have been difficult for customers. Coffee shops often act as “third places” where community and connection can develop outside the home or work. Third places often become essential to the fabric of a neighborhood, acting as a social leveling space where people of all social and economic classes can interact. These spaces can become as familiar to people as their homes and workplaces, meaning the sudden loss can feel just as heavy. Communities can lose cohesiveness and identity if too many of these shared spaces disappear.

We moved to a four-day work week because everyone is so exhausted. We changed our pay structure so people could still afford to live. I saw a lot of my peers in the coffee industry just go through hell. casey gleason, marigold coffee

In Los Angeles—where I live—we permanently lost Casa Cubana, Cuties LA’s brick-and-mortar location, the iconic 101 Coffee Shop, made famous by the film Swingers, and others. Many of these cafés closed in March 2020 and never reopened, leaving the people that loved these spaces without a chance to say goodbye. People were stuck saying goodbye in Instagram comments instead of being able to patronize the business one last time.

Before the pandemic, Cuties LA hosted kickbacks for the queer community, art-making gatherings, holiday events for folks unable to go home, and more. Some events moved to virtual spaces during COVID, but in August 2020, they announced their permanent closure on Instagram. “We’ve been accumulating debt to our landlord,” founder Virginia Bauman said in Cutie’s goodbye post. “While I considered appealing to the community to ask for increased financial support, I can’t in good conscience ask you to fund a space that is not being used to generate value for us. If I were to ask you to do that, I’d have to recognize that money from the queer community would be moving directly into the pockets of our landlord. This is incongruent with our values.” Though Cuties lives on in pop-up events under new CEO Sasha Jones, the loss of the safe space they provided for queer folks is still felt.

A Chance For Something New

While the loss of coffee shops as community spaces is enormous, perhaps even more devastating is the number of coffee workers whose jobs never returned. Some left the coffee industry entirely, though others were able to use the sudden change to fulfill their own dreams.

When Forth Projects in Winnipeg, Manitoba, closed in March 2020, manager Jordan Cayer opened a coffee delivery service with a coworker. They launched Never Better Coffee, starting slowly with coffee deliveries and pop-ups. After two years, Cayer recently opened Never Better’s first full-service café in collaboration with restaurant Bonnie Day.

In 2023, recovery from COVID continues. The recovery process hasn’t been linear, and many are still emotionally dealing with COVID closures’ impact on their careers and businesses. For many, it was the end of an era. While there are still coffee shops for people to go to, the loss of community spaces has been disorienting, a rupture in their life that needs to be contended with. It has been challenging, and we still have a ways to go before the coffee industry fully recovers.

The first cafe I visited once spaces began reopening was Eightfold Coffee in Echo Park. The atmosphere was a little charged—people were still trying to navigate the area, mentally calculating what six feet of space looked like, shuffling around to stay a safe distance away from the person in line in front of them. A familiar feeling washed over me as I opened my laptop, catching snippets of chit-chat between customers and watching baristas make and deliver drinks. Perhaps things won’t ever look as they did a few years ago, but the familiar beats of a coffee shop remain.