Why would one of the world’s most prestigious coffee farms cut down half its coffee trees?

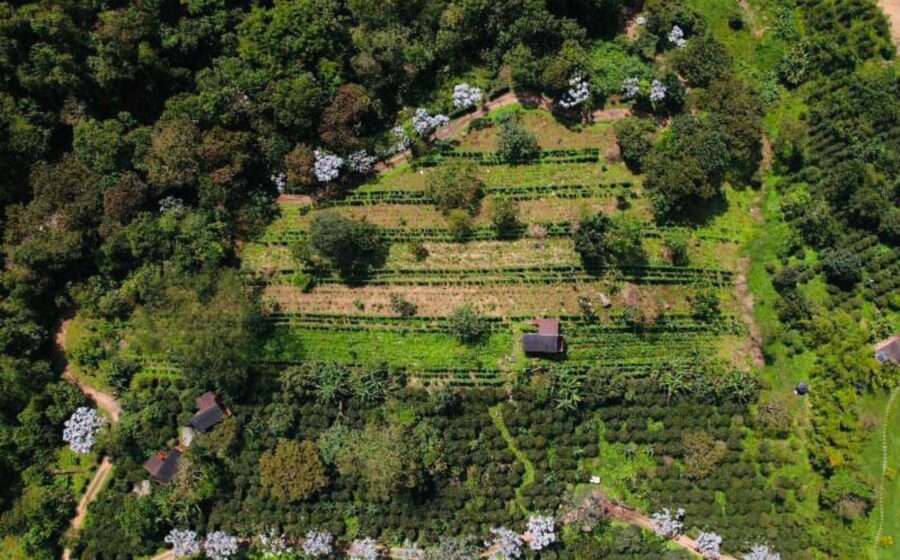

La Palma y El Tucán in Zipacón, Colombia, is a specialty coffee farm known for its rare varieties and innovative processing techniques. Many baristas and roasters seek coffee from the farm for coffee competitions, including the 2019 World Barista Champion Jooyeon Jeon of Momos Coffee. Despite the accolades, in 2017, founder Felipe Sardi took a drastic step toward changing the ecology of his farm.

“Until 2017, the farm was [managed] under conventional practices. We were using chemical fertilizers, chemical herbicides, and chemical pesticides for the first years,” says Sardi. But Sardi became convinced of the necessity of biodynamic farming practices when studying sustainable agriculture at the University of Melbourne and the Permaculture Institute of Australia. After fieldwork in Malaysia and Indonesia, Sardi returned to Colombia with a new agricultural vision.

“I started seeing farming practices differently, that it made more sense to work with nature rather than against it,” he says.

Coffee is conventionally farmed as a monoculture, meaning a farm or a plot of land grows a single crop. Farms that utilize monoculture practices often rely on human intervention and chemical inputs such as nitrogen fertilizer to maximize yields. Over time, this approach can deplete nutrients from the soil and lead to erosion.

But advocates of regenerative agriculture see the farm as “a closed loop” where each crop is part of a larger ecosystem that includes other plants, fungi, insects, and animal life—and some in the coffee industry see it as a way to maintain more sustainable farms and produce better coffee. However, adopting regenerative practices comes with a price: “If you want to achieve balance, you have to sacrifice yield,” says Sardi.

First, Sardi needed to convince his employees.

“It wasn’t well received by my team here in Colombia. I think we cut down 42,000 [coffee] trees,” he says. The biodynamic farming methods that Sardi implemented aim to create more biodiversity on the farm through polyculture and animal husbandry. Beyond simply using organic compost instead of chemical fertilizers, this approach imitates the tropical forests where coffee grows in the wild.

“I planted 24 different species at three different strati,” says Sardi. “At the ground level, we have perennial cover crops. These help retain moisture and don’t compete with the roots of the coffee. At the mid-level, we have avocados, bananas, plantains, lemons, and mandarin oranges. The high canopy provides shade, and the leaves create nutrients for the soil and attract bees for pollination.” Despite initial hesitation, Sardi noticed improvements immediately, opening up the question of how regenerative agriculture can be used more broadly to enhance coffee farming and build a more sustainable future.

It Starts With Soil

Despite the multiple new techniques Sardi implemented at La Palma y El Tucán, he says everything starts with the basics. “When you talk about agriculture, you begin with soil,” says Sardi. “At the core of regenerative agriculture is soil health.”

It’s a sentiment shared by Sam Knowlton, founder of Soilsymbiotics, a Colorado-based consulting firm that helps farmers create regenerative agronomic systems. “If you have truly healthy soil, you’re going to have healthy plants, healthy fruits, and healthy leaves,” says Knowlton.

Knowlton identifies three interrelated aspects of soil health: the physical structure, the biology, and the chemical composition.

“The physical property of the soil has to do with how it’s aggregated and whether there’s a sufficient gas exchange within the soil,” says Knowlton. “When you have good soil structure, there are habitats for microbiology, which is essential for cycling nutrients or building water-holding capacity. Essentially it acts like the immune system for the plant, so it defends the plant from pathogens and diseases.”

The chemical composition refers to the soil’s mineral content, as determined by the local geology. Each soil is unique, so there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to regenerative agriculture. “What works on one farm may not work on another farm. It’s very context-dependent,” says Knowlton.

Healthy soil not only fosters a balanced ecosystem, but it also leads to better quality produce. “Regenerative agriculture is about maximizing the genetic potential of crops,” says Knowlton. “A good measure of regenerative agriculture is the nutrient density of whatever is harvested.”

Whether it’s an apple or a tomato, greater nutrient density means more flavor compounds in the harvested produce. In coffee, higher nutrient density in the coffee cherry can lead to higher cupping scores, as evaluated by licensed Q graders.

“If you have better nutritional quality, you can have better flavor,” says Knowlton.

Sardi agrees. “When you talk about the chemical compounds that are the precursors of flavor in coffee, you need to talk about nutrition,” says Sardi. “Healthier soil has the potential to produce more complex flavors.”

Getting Off The “Chemical Gerbil Wheel”

Farmers interested in implementing a biodynamic approach face an uphill battle. As a result of colonization and the so-called “Green Revolution” of the 1960s, coffee is overwhelmingly grown in chemical-dependent monocultures—on many coffee farms, the only crop is coffee.

“One of the first challenges to overcome is that coffee is entrenched in this chemical agriculture paradigm,” says Knowlton. “How do you get off of this chemical gerbil wheel, where the application of chemical fertilizers and pesticides requires the application of more chemical fertilizers and pesticides year over year?”

Knowlton points to coffee leaf rust—the notorious fungus that has plagued coffee farms across Central and South America—as one symptom of the problem.

“These farmers are using 3-5 fungicides every year that basically keep rust at a level that’s not impacting them economically. It doesn’t get any better, and it costs more and more money,” he says. “This all affects the soil health, the beneficial fungi in the soil, and the nutritional integrity of the plant, which affects the flavor and quality.”

Regenerative agriculture methods employ alternative means of dealing with harmful fungi and pests. “By implanting a more integrated, biological system that focuses on plant nutrition, we’ve been able to [help farmers] eliminate chemical fungicides altogether, which provides huge savings to the farmer, both in terms of money and labor,” he says.

Knowlton also believes regenerative agriculture is better for the people that live and work in farming communities. On his first trips to coffee farms, Knowlton was shocked to see farm workers applying chemical pesticides and herbicides without protective gear.

“That’s something that’s not really considered: the health of the workers on the farm. These sorts of chemicals have been proven to be detrimental to health in several ways,” says Knowlton. One 2019 study found that exposure to glyphosate-based herbicides increased cancer risk by up to 41%.

Knowledge is Power

Knowlton wishes the narrative in the coffee industry would shift from coffee varietals and processing methods to implementing more sustainable agriculture systems.

“Any new varietal is only going to be as good as the soil it’s grown in and the quality of the agronomic system that’s in place,” he says. “[New varieties] are not accessible to many farmers and very centralized. More knowledge would spread easily, and it belongs to the producer.”

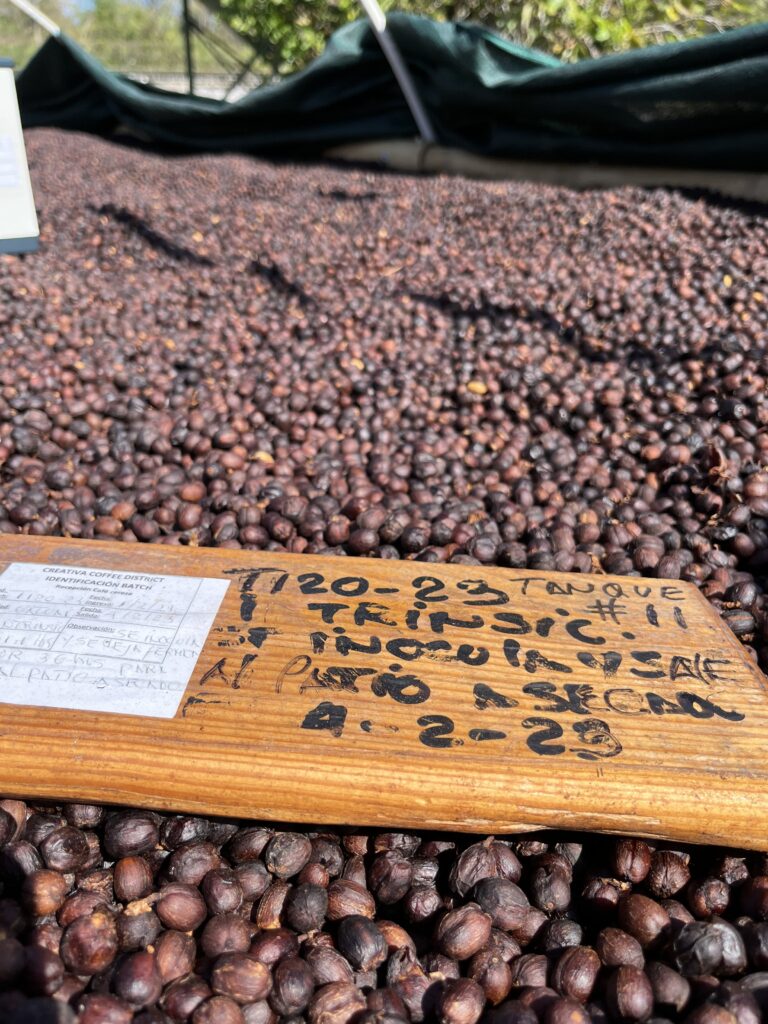

Having seen the impact of regenerative practices on his farms, Sardi co-founded a new business, Biodiversal, focused on providing resources and training for farmers interested in transitioning to more sustainable models. Biodiversal recommends farmers plant coffee-associated crops, such as kidney beans and turmeric, which help enrich the soil and provide additional revenue streams. The company’s new factory in Tolima, Colombia, produces biofertilizers such as biochar, a carbon residue from biomass sources. Many studies have shown that biochar can help revitalize nutrient-deprived soil.

La Palma y el Tucán has long purchased coffee cherries from other farmers in their region and will continue to support local farmers through Biodiversal. “We’re prioritizing the neighboring farms that we work with,” says Sardi. “For every kilo of cherries we buy, they receive a kilo of biochar that Biodiversal produces.”

For Sardi, regenerative versus conventional agriculture isn’t binary but a spectrum where principles and best practices must be weighed against the economic realities of farmers. With plans to expand Biodiversal to Costa Rica in the works, he hopes more farmers will embrace a more holistic approach.

“[We] don’t judge people that do things traditionally—we were using chemical fertilizers, chemical herbicides, chemical pesticides just a few years ago, “he says. “It’s a matter of welcoming everyone who wants to change from monoculture to polyculture.”