Dr. Hans-Jürgen Langenbahn has seen a lot in his 20+ years in the coffee industry. He’s spent nearly 15 years at Happy Goat Coffee Company in Ottawa, Canada, where he is head coffee roaster. In 2021, he founded the Zero Waste Coffee Project, aimed at highlighting the ways different actors in the coffee industry can reduce waste—or even turn it into resources.

But he says something stood out to him in a recent interview with Rudi Dieleman, director and co-founder at PectCof B.V., a company that makes a food emulsifier and stabilizer from coffee pulp. “Coffee trees bear cherries, not beans,” Dieleman told Dr. Langenbahn for one of his blog posts.

Dieleman noted the irony that only a small percentage of those cherries are used; the bean is actually the seed of the coffee fruit. “The cherries are the crop! Why shouldn’t a farmer get the value for his whole crop instead of only 20% of it?” Dieleman asked.

If you’ve ever had a beverage brewed with cascara, the skin and pulp of the coffee cherry, you’ve likely seen claims related to its upcycling potential. Many cascara companies say they aim to reduce waste and emissions while also supporting farmers, and some initial research supports this.

For example, the Coffee Cherry Company has estimated that every truckload of purchased cascara diverts 280,000 pounds of fruit from decaying in fields. This in turn prevents 101,000 kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) from being emitted, and creates $1,200 in additional income for farmers.

But because the cascara and coffee fruit beverage market is still relatively new, reliable data on farmer revenues is scarce. Nor is there a grading system for cascara, like the Q Grading system long used for arabica beans, or the one being developed for canephora, that can set expectations around pricing and profit. From the retail perspective, says Dr. Langenbahn, “the majority of claims about farmer income are based on trust,” especially when coffee businesses purchase through a third party.

Cascara is a significant byproduct of coffee production—but while coffee is a prized commodity, cascara is a “nice to have” extra that is, more often than not, overlooked. Coffee fruit beverages are still a small segment of the global coffee and food market, though many expect demand for such products to rise.

But even amidst growing interest in the category, it remains unclear how farmers will ultimately benefit.

Tapping Into Cascara’s Value

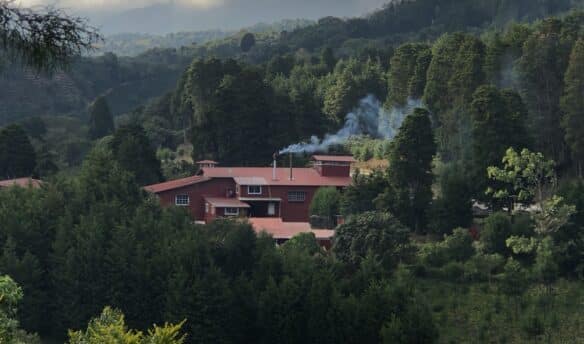

“Cascara’s potential is so big, and the impact on the coffee industry could be amazing,” says Moises Hidardo Hernández. Hidardo Hernández is a fourth-generation coffee farmer and co-founder of Cascaritas Farm, a 10-hectare, family-run estate dedicated to specialty coffee in western Honduras.

Cascara is especially relevant now, he says, when climate change and a lack of workers—many of whom have emigrated to the U.S. for other opportunities—are hitting farmers hard. Hidardo Hernández says that Honduras’ coffee production has decreased from 10 million bags 40 years ago to about six million today.

Cascaritas Farm began exploring cascara 10 years ago, just as Hidardo Hernández was studying business administration. “It’s not easy to reinvest coffee sales, like to build a new warehouse or patio,” he says. “[Many] producers have loans to maintain their farms. For this reason, we analyzed what other products we can obtain from the farm.”

They began processing cascara a year later. Around the same time, they opened a cafe in Santa Rosa, where they offer cascara infusions using husks from different coffee processing methods, including washed, natural, and red honey. While all create different profiles, Hidardo Hernández says the naturals are his favorite. “They’re sweeter, very clean,” he says.

Although cascara exports and overall sales are tiny compared to green coffee, the novelty of the cascara market has created an early advantage for farmers to set their own prices. Diego Guardia, general manager of Hacienda Sonora in Costa Rica, says the 100-hectare farm began natural-processing cascara around 2005. Though Guardia didn’t share specific prices, he says they are based on “demand and offer.”

At the Gunung Tilu coffee cooperative in West Java, Indonesia, coffee pulp often piles up and creates waste and emissions, Arka Irfani and Hisyam Bin Ahmad H.M told the Zero Waste Coffee Blog. The two are founders at the Bell Society, which buys Gunung Tilu’s coffee pulp to create imitation leather for furniture and fashion accessories. The cooperative says it earned roughly $140 per U.S. ton of pulp sold in 2024.

Meanwhile at Cascaritas, cascara pricing is based on the pound, but Hidardo Hernández says that its low water content (versus that of green coffee) means this requires a lot of cascara. Ten years ago, he sold cascara for $2.50/lb, and today he sells it for $4.50–$5/lb.

Hidardo Hernández says cascara can give farmers a new source of revenue, but that direct-trade relationships are the most sustainable option. “It’s better for the producers to know the final customers, so we can respond to roasters’ specific needs and establish long-term, multi-year relationships,” he says. He has partnerships with roasters in the U.S., Japan, Switzerland, Germany, and Denmark.

So far, cascara, which is the Spanish word for “husk,” is mostly exported from Latin American nations. This is because countries like Honduras and Costa Rica have developed “a robust infrastructure” since the mid-2000s to make coffee cherries “export-ready,” says Muna Mohammed, founder and CEO of roastery Eight50 Coffee in Ontario, Canada.

As part of the Ethiopian diaspora, Mohammed grew up drinking hashara, the word used for cascara in Ethiopia. Mohammed says it’s traditionally consumed in specific regions, especially by the Oromo and Harari people of eastern Ethiopia, in the Jimma and Arsi zones of the Oromia region, and in some parts of the South West region—often with milk and spices when they are available. “Hashara was a staple in our pantry,” Mohammed says of her upbringing.

Mohammed was inspired to enter the coffee industry because her late grandfather was a coffee farmer. Although she brings hashara from Ethiopia for personal consumption, infrastructural limitations make it harder to export in large quantities—there was no export category for hashara until recently—so Mohammed sources the cascara for Eight50’s award-winning, ready-to-drink beverage from Costa Rica.

She named the sparkling, flavored coffee cherry tea beverage Cascara Hashara, both to recognize the word most people use as well as to honor the coffee cherry’s roots in the country that has been dubbed the birthplace of coffee.

But during her last visit to Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, Mohammed observed a market ripe for change. Ethiopian coffee professionals “are taking notice of certain communities’ ancestral ties to this beverage,” she says, and have begun serving it in cafes. Meanwhile, Mohammed says the farmers and exporters that she’s spoken with are shifting, too. “They’re starting to understand that what was once only considered for local consumption is export-worthy. There is a demand for it.”

A Grading System for Cascara?

Founded by Honduran entrepreneur Ruben Soto, BioFortune is a biorefinery and tech hub working to add value at origin. By partnering with thousands of farmers in Honduras and Guatemala—including Cascaritas Farm—the company transforms agricultural waste, including coffee cherries and tropical fruits, into concentrates that can be used in everything from drinks to personal care products. To help farmers combat volatility and build a more stable income, BioFortune purchases a large portion of farmers’ agricultural products, and also shares its profits with them.

There are more market opportunities for cascara now than ever, especially since the European Economic Area (EEA) greenlit its use in non-alcoholic beverages in 2022. For now, part of cascara’s economic potential lies precisely in farmers’ ability to control the pricing mechanisms. However, the lack of an established price-to-quality ratio can also discourage buyers, says Dr. Langenbahn.

Although the U.S. doesn’t have the same regulatory barriers as the EEA, Ryan McDonnell, CEO of cascara beverage maker Alldae, says that the current cascara market lacks clear expectations for consumers as well as coffee businesses. “As a Q Grader, I’ve had cascara that was and wasn’t palatable. But we don’t have a clear-cut idea of defects in cascara yet. We haven’t developed commodity cascara, let alone specialty cascara,” he says. McDonnell says he’s tasted similar-quality cascara priced at $2/lb and $50/lb.

It’s for exactly this reason that Dr. Langenbahn, who has seen cascara priced for between $1–$30/lb, has proposed establishing a grading system “so that its value is clear for everybody in the industry.” Though he has made some progress in creating partnerships to support such a system, his efforts have faced logistical challenges.

Dr. Langenbahn believes future work is still needed to build trust and drive the growth of cascara businesses across the value chain. “Without a grading system, prices are only based on feelings, not on economics,” he says.

Reducing Waste, Creating Value

In consuming countries, beverage producers are some of the biggest champions for cascara’s growth. “Producers have told me the most important thing is to build demand for cascara,” says McDonnell. “We want to grow our business to help stabilize demand, and then see how we can best allocate sourcing to make an impact for [producers].”

Though beverages are a visible part of the cascara market, the potential to scale is limited. Some cooperatives are processing cascara into soil amendments like biochar and fertilizer. Cafesmo, a cooperative of coffee farms in western Honduras co-founded by Hidardo Hernández, adds minerals to cascara during composting to neutralize the effects of compounds like caffeine and tannins. It offers the resulting organic fertilizer to farmers for free, so they can cycle it back into their next harvest.

The early signs of a mindset shift that Muna Mohammed of Eight50 Coffee saw in Ethiopia are spreading. Hidardo Hernández says the last few decades have brought big changes—including in his own family.“My father [used to be] very traditional,” Hidardo Hernández says. “When I suggested cascara infusions for the cafe, he told me I was crazy,” and that it was better suited for compost. But once U.S. roasters expressed interest, the father saw his son was right—and Cascaritas is now pursuing new partnerships and new possibilities.