[T]o get a look at Istanbul’s coffee culture, both old and new, it’s best to start in Eminönü. The historic neighborhood juts out between Istanbul’s two iconic waterways, the Golden Horn and the Bosphorus Strait, just down the hill from the city’s great mosques and palaces. From the daily commuters rushing to make their ferry to the Asian side to the seagulls circling above the vendors selling fish sandwiches and stuffed mussels from food carts, it’s a bustling neighborhood in full motion.

The twentieth century saw traditional Turkish coffee culture largely replaced with instant coffee, but the old ways are still preserved in the Spice Bazaar, where tourists and locals alike go to sample Turkish delight and pungent spices. One of the main draws for the locals is Kurukahveci Mehmet Efendi, a coffee company dating back to 1871. Although the famous brand is available by the tin in grocery stores nationwide, even worldwide, long queues of customers line up daily to buy freshly fine-ground coffee from the company’s headquarters, immediately outside the west entrance to the bazaar. The brand is iconic, but the coffee being roasted is low-grade Brazilian.

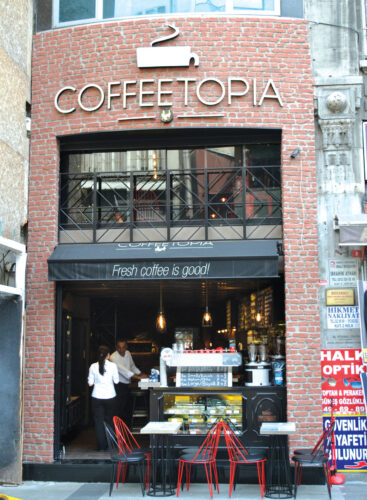

A few blocks away, toward the stunning Hagia Sophia, a café named Coffeetopia presents a new vision for Turkish coffee. As indicated by the wide array of manual brew methods that line the counter, Coffeetopia is a haven for coffee lovers. The carefully designed space is the latest project from specialty coffee pioneers Şerif and Özlem Başaran. Since 2007, the husband and wife team have been quietly building a coffee empire in Turkey. Şerif wears multiple hats, including consultant, Specialty Coffee Association of Europe-certified instructor, and World Barista Championship technical judge, but spends most of his time running their roasting company Coffee Factory, which supplies more than a hundred cafés in Istanbul. Their wholesale accounts range from commercial to craft, including Çekirdek, a Kadıköy district café widely considered Istanbul’s first specialty coffee shop. Özlem, who speaks English with a soft Australian accent, manages Coffeetopia, which is the Başaran’s first foray into the Turkish retail market.

The twentieth century saw traditional Turkish coffee culture largely replaced with instant coffee, but the old ways are still preserved in the Spice Bazaar, where tourists and locals alike go to sample Turkish delight and pungent spices.

A soft opening during Ramadan, the Islamic month of fasting, gave Özlem and her team of baristas a chance to ease into operation. The Başarans have a dedicated following of home baristas and they knew their first café would be highly scrutinized. Less than three months in, business is already booming. “Word of mouth is our best marketing,” says Özlem. Their overnight popularity is little wonder, considering Coffeetopia’s winning combination of location, product, and execution.

With two floors of seating, by Istanbul standards Coffeetopia is a spacious café. The matte black interior is well complemented by the embroidered white button-ups worn by the baristas. The mirrors that run the length of the interior lend the space a certain refinement, but perhaps it’s the Sanremo Opera espresso machine that steals the show. Alongside coffee professionals like John Gordon, Şerif served as a consultant for the Opera, which he calls, “a dream machine.” It features multiple programmable presets, controllable flow rate, and built-in scales in the drip tray. Flanked by a pair of Ditting grinders, the Opera offers shots of Coffee Factory’s espresso blend and a rotating cast of single-origin coffees. The thick, syrupy house blend is evocative of espresso from Seattle’s famed Espresso Vivace: dense flavors of dark chocolate and caramel. It tastes good straight, but really sings in a cappuccino, which are prepared Australian style, with a sprinkle of cocoa powder on top.

[I]n many ways, the Başarans story is the story of Turkish specialty coffee. The Başarans started in the industry in 2003 while living in Australia, where they owned a Michel’s Espresso franchise. There Özlem and Şerif were trained by the freshly crowned World Barista Champion Paul Bassett. The franchise was successful, but their lives took a dramatically different direction when Şerif was invited to help with a specialty coffee and tea expo in Istanbul. While in Turkey, Şerif saw a tremendous opportunity in a developing market. International chains like Starbucks and Gloria Jean’s were rapidly expanding around the country, but the boutique market remained largely untouched. The few independent shops that did exist were importing coffee from major European brands like Illy and Julius Meinl. The couple sold their shop and set out to start a new business.

Initially, the challenges were manifold. Turkey lacked basic barista equipment such as tampers and milk pitchers, so Şerif worked with local fabricators to make them. Local baristas, however, were reluctant to change. They preferred to heat milk in Turkish coffee pots and tamp with the attachment on the coffee grinder. Even though these techniques produced burnt milk and unevenly extracted espresso, baristas defended the latter practice by pointing out it was commonplace in Italy. “You can’t say the Italians are wrong,” Şerif says with a chuckle.

Two important events altered the landscape. In 2008, the Specialty Coffee Association of Europe awarded Şerif “Most Passionate Coffee Educator.” The affirmation from an international body of coffee professionals lent credibility to Şerif and helped build his reputation as a coffee expert. Momentum shifted even more with the advent of officially sanctioned barista competitions. “The competitions helped a lot because the baristas had to follow the rules,” says Şerif. Şerif himself has become a fixture of international barista competitions, serving as a technical judge at the past four World Barista Championships.

The impact of the barista competitions is most clearly seen at Geyik Coffee Roastery and Cocktail Bar. Geyik, which means deer in Turkish, was founded by 2013 Turkish Barista Champion Serkan İpekli. İpekli previously worked for Coffee Factory, but left to help their wholesale account A Cup of Joy start a new café. After representing Turkey at the 2013 World Barista Championship in Melbourne, İpekli set out to open his own space in Cihangir, the artistic and cultural neighborhood that lies across the Golden Horn from Eminönü.

The narrow, shotgun-style space is only slightly larger than a hallway, but that doesn’t stop İpekli from roasting all his coffee in-house on a two-kilo Has Garanti roaster. İpekli, who sources Geyik’s green coffee in partnership with Coffee Factory, enjoys being able to experiment with different roast profiles and blends. Inspired by Athens’s Tailor Made, at night Geyik becomes a cocktail bar, with a menu of classic cocktails curated by İpekli’s business partner Yağmur Engin.

[I]f the mosques and bazaars of Istanbul’s old city denote Turkey’s Ottoman heritage, the symbol of Modern Turkey is undoubtedly the shopping mall. Istanbul has boasted Europe’s largest mall for almost a decade, but the sheer number of malls is more shocking than their size. Almost every subway stop has its own shopping center, and somehow they all seem to be filled with shoppers with money to spend. One of the staggering number of malls, Kanyon, in the heart of Istanbul’s financial district, has carved out a niche as a purveyor of luxury goods. Whether it’s Danny Meyer’s international juggernaut Shake Shack or English department store Harvey Nichols, Kanyon is the place where refined Istanbulites go to shop, eat, and even exercise. It’s here, just inside the main entrance, that Petra Roasting has set up a ground-breaking new kiosk.

Against a sea of glass and concrete, the wooden kiosk pops from the foreground. The simple structure offers an even simpler menu: filter coffee and espresso drinks for take-away only. Espresso at the Petra kiosk is prepared with a well-polished La Marzocco Linea, which sits perpendicular to a row of Hario V60s. A Mazzer Robur and a Baratza Forté ensure the coffee is freshly ground. The kiosk started as a pop-up shop, but the unexpected popularity of the stand has led to plans to keep it open year round. The open-air format exposes thousands of people each day to specialty coffee, most of whom have never seen a pour-over device. Petra, whose roastery is located in nearby Gayrettepe, has also recently enjoyed some international exposure. Founder Kaan Bergsen, who cut his teeth in the industry while living in New York, came in fourth place in the World Coffee Roasting Championship in Rimini, Italy.

“Our philosophy is to roast in small batches,” explains barista Cem Bozkuş. “We always trust our palates and check the quality in every stage.” Currently, Petra partners with InterAmerican and Nordic Approach to source their coffee. Although it’s less cost efficient, the decision to source coffee through foreign coffee importers is prevalent among Turkey’s quality-focused coffee roasters. This is the only way micro roasters can source world-class green coffee, but the red tape of Turkish customs can be a difficult obstacle to overcome. “You always can have problems with laws and customs in Turkey,” says Bozkuş.

Local roaster Kronotrop is taking a similar leap into the mainstream. Visitors to their Cihangir café will find a space on par with the finest shops New York or London have to offer. Black and white Anatolian tiles line a counter that holds an impressive array of equipment, including a La Marzocco Strada EP, Mahlkönig EK-43, and massive Japanese cold-brew towers. The luminous atmosphere attracts an urbane clientele, but what really sets Kronotrop apart is their drive to source and roast the finest coffees possible. To do this, founder and head roaster Çağatay Gülabioğlu recently joined forces with renowned chef Mehmet Gürs and his Istanbul Food and Beverage Group. By partnering with Gürs, Gülabioğlu has been able to outfit a state-of-the-art roasting facility complete with Turkey’s first Loring S15 Falcon roaster, which recently arrived from America. The roaster will give Gülabioğlu increased control over his roasts, including the ability to duplicate previous profiles. Like Petra, Kronotrop faces the obstacle of Turkey’s harsh importing restrictions, but thanks to the American importer Ninety Plus Gülabioğlu has been able to roast some of the highest quality coffees on the market. A wider audience is enjoying their wares now that Kronotrop is being served in all of the Gürs restaurants, including the award-winning Mikla. Despite enormous advances, Gülabioğlu’s focus is still on the future. “Our ultimate goal is to source our own coffee and to go to the farms.”

[A] man walks into Kronotrop’s Cihangir café. After scanning the menu he asks, “Do you have any tea?” The tattooed barista responds, “Unfortunately we don’t have tea. We do have coffee.” The potential customer quietly leaves with a shrug, revealing one of the greatest challenges the fledgling coffee community in Istanbul faces: Turkish tea.

Nonetheless, the Young Turks who are creating this new specialty coffee culture are optimistic about the future. As European visa restrictions are being lifted, a growing number of Turks are traveling abroad and developing a taste for specialty coffee. Likewise, the booming economy in Turkey is creating a growing middle class, with expendable income for food and drink. “This is a new concept, but we like it,” Şerif Başaran says. With their first shop only a few months old, a second store is in the works, with the possibility of further expansion. Özlem Başaran says, “The reaction of the customer is our motivation.” If current momentum continues, the Başarans won’t have to look far for more inspiration.

— Michael Butterworth is a barista and writer based in Louisville. He co-founded The Coffee Compass.