It’s been five years since I last visited my home country of Indonesia. I finally returned this past summer, with the initial goal solely to see family and friends. But somehow, it still ended up being a coffee-origin trip, for which I felt immensely grateful.

Thanks to Drew Burnett and Jen Green, two longtime Jakarta-based ex-pat coffee professionals, I saw a few farms and met producers along with post-harvest processors. In Indonesia, processors refer to washing station owners/managers who buy whole coffee cherries from farmers. Some processors also run their own farms, while others do not. They are turning out clean, delicate coffees that belie the country’s reputation—primarily due to Sumatra, an island that produces 70% of Indonesian arabica coffees—for heavy, earthy cups.

I visited a handful of small farms and roasters in Java and Bali. I was wowed by the state of the country’s specialty scene compared to my last visit half a decade ago. But people have been working to improve Indonesian specialty coffee for the past two decades. At the same time, obstacles still lie ahead for producers. The three farmers/post-harvest processors I met during the trip kindly agreed to sit down for interviews over Zoom. We discussed the positive changes wrought by Indonesia’s rise as a specialty coffee-producing and consuming region and the problems farms are experiencing this year, such as inflation and reduced crop yield.

(Note: I conducted the interviews in Indonesian. The quotes have been translated and slightly edited for clarity.)

Klasik Beans

We cannot speak about specialty coffee in Java, if not all of Indonesia, without mentioning Klasik Beans. The co-op, located in Puntang, West Java, is one of the pioneers in the country’s specialty processing. In the later 2000s, Klasik regenerated historical but defunct coffee-growing areas like Puntang and provided training to local farmers. In doing so, the co-op helped kickstart the specialty coffee boom in Indonesia.

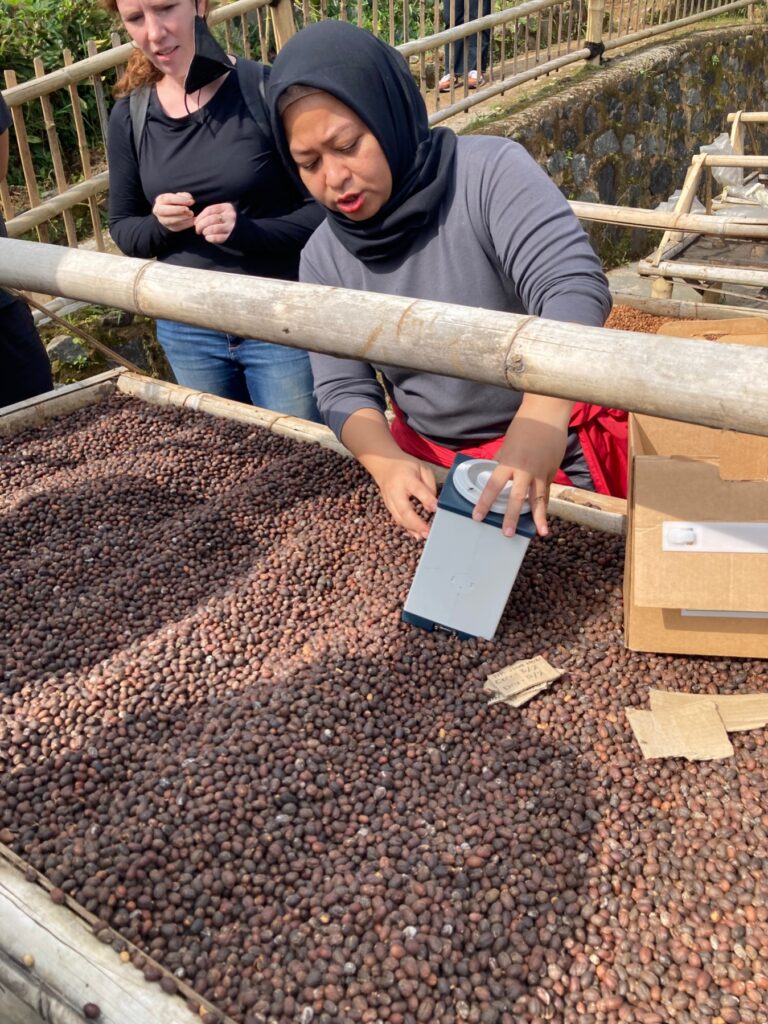

Uden Banu, Klasik’s quality control and operational manager, hosted us during our visit and gave us a tour of the facility.

Banu has known Klasik’s founder Eko Purnomowidi (or, as we both refer to him, Pak Eko) since he was a child. Purnomowidi was a good friend of Banu’s parents, and later they both worked together at Volcafe in Medan, a central coffee hub in Sumatra. Medan was where Banu cut his teeth, learning the ins and outs of coffee processing and trading—how to dry properly, how to use a gravity table for sorting, and how to roast and prepare samples for cupping.

Klasik’s roots began around 2006. At first, the Klasik team, with the help of local search-and-rescue volunteers, scoured West Java to look for potentially ideal growing areas. Originally, the area around Puntang, where Klasik now stands, was supposed to be turned into a vegetable farm. But the co-op convinced the farmers to replant and grow coffees with the promise of market demand. Then they spent most of 2007 advising and guiding producers on coffee farming practices. “We hadn’t yet purchased coffee in 2007,” Banu tells me.

Along with advising farmers, Klasik also promised to pay more for coffee cherries. “To give you an idea,” says Banu, “in 2008, coffee cherries were selling at Rp. 1,500/kg [US$0.10/kg or US$0.04/lb in today’s exchange rates].” Hardly an incentive for replanting coffee. But that year Klasik paid Rp. 5,000/kg [US$0.33/kg or US$0.15/lb], with the condition that farmers would only pick ripe cherries.

Klasik has always emphasized education and knowledge sharing with local producers. “To take a small example, in 2008, 2009, farmers were still buying coffee seeds,” Banu says, which meant that farmers were not self-sufficient enough to plant new trees using their own seedlings. “Once we entered [West Java],” continues Banu, “we taught them how to build nurseries and choose good seedlings.”

“It’s only at the end of 2008, if I’m not mistaken, that we started processing, and our first export took place in 2009.” Sweet Maria’s, Intelligentsia, and Allegro Coffee Roasters were among Klasik’s first American buyers. “The local market hadn’t really formed at that time,” says Banu.

Funnily and predictably enough, only after US third-wave roasteries purchased green coffee from Klasik did local Indonesian roasters become interested in the co-op. “For us,” says Banu, “local and export sales [at this point] are fairly equal—60% local, 40% export—though there is more local consumption.”

Nature conservation and reforestation form a vital part of Klasik’s mission. Klasik’s website proudly proclaims its coffees as “100% deforestation-free,” This mission informs how they approach farming and processing. Purnomowidi has provided consultation on eco-friendly growing practices to other farms and co-ops over the years, including an East Timor co-op I highly admire, Cafe Brisa Serena.

This year, many farms are reeling from hikes in fertilizer prices due to the war in Ukraine. But that hasn’t been an issue for Klasik since Banu says the co-op uses very little fertilizer: “For us, fertilizer is not an issue. In West Java, fertilizer price is low on our list of problems because we rarely use it.”

Still, 2022 has been a challenging year for Klasik. According to Banu, “the foremost problem on the ground is the drop in harvest yield.” For him, there are two influencing factors: “One is rainfall, the other more significant factor is the five-year cycle [of the coffee plants]—I believe in that.” Since 2016 and 2017 were tremendous harvest years, Banu thinks that coffee trees would go through five years of declining yield, with 2022 being the nadir.

While the five-year cycle may be a crucial factor, the amount of rainfall Indonesia received this year—30% higher than average—is far from negligible. We’ll see that this affects harvests in other coffee farms more drastically.

Java Halu Coffee Farm

When I met her in 2016, Rani Mayasari was an active cafe owner, with numerous branches of her coffee shop, Yellow Black, all across the country. Now, she is fully focused on farming and processing and is the proprietor of Java Halu Coffee Farm. I had a chance not just to cup her current harvest but to check out her processing station.

Hailing from Gunung Halu, a coffee-growing region west of Bandung, the capital of West Java, Mayasari originally did not know anything about farming or roasting as a cafe owner. Her initial dip into green coffee sourcing was simply to secure an annual supply of beans for her shop. “I started visiting farms and meeting producers,” she says. In 2014 Mayasari acquired her first farm: a one-hectare plot of land in Gunung Halu.

Almost 80% of the coffee farm laborers Mayasari works with are women. “There are a lot of women in the fields,” says Mayasari, “because West Bandung is a source of female migrant workers [TKW/Tenaga Kerja Wanita—the official Indonesian term, literally “female labor/workforce”].” But many women who work abroad as housemaids are often younger, and those in their 40s or approaching that age tend to stay in their home villages and become farm laborers.

Production in the past year has also proven difficult for Mayasari. Besides general inflation, she also had to deal with a considerable dip in overall crop yield. She had fewer coffee cherries she could purchase from other farmers, which created a huge uncertainty in her ability to fulfill orders.

“As a result,” Mayasari laments, “many speculators came and ruined the stock of cherries [in West Java]. For instance, coffee companies from Medan purchased green beans from West Java to be brought back to Medan to fulfill their own contracts.” So the amount of cherries that local Javanese processors had access to became even scarcer.

The remaining available cherries carry a hefty price tag. Last year, Mayasari could buy cherries from other farmers in West Java at a maximum of Rp.9,000/kg (US$0.60/kg or US$0.27/lb). This year, prices shot way up, selling at about Rp.16,000/kg (US$1.07/kg or US$0.49/lb). “It takes 7kg of coffee cherries to produce 1kg of green beans,” she explains, “so it already costs over Rp.100,000/kg (US$6.67 or $3.03/lb) to produce the raw material.”

Specialty processors like Mayasari have had to sell their green coffee at a higher price. She grimly estimates that no one is making money this year. Even if farmers could fetch a high price for their cherries, that doesn’t make up for the steep decline in crop yield. “We are already feeling the effects of global warming,” she says. “Seeing how rain and precipitation have become uncertain, we have to learn again from nature—when to plant, when to nurse and fertilize, etc.”

Tuang Coffee

Andre Hamboer is the founder and operator of Tuang Coffee—‘Tuang’ is Indonesian for ‘pour.’ Besides running a cafe with the same name in Jakarta, Hamboer is a processor focused on coffees from the Manggarai regency in Flores, an island in central Indonesia.

Those who follow coffee competitions may have heard of Tuang before. 2020 Indonesian barista champion Mikael Jasin, from Common Grounds and the experimental processing company Catur, used Manggarai lots he processed with Tuang for his 2021 Milan World Barista Championship routine.

Though Hamboer grew up in Jakarta, his father often took him to Ruteng, a city in Flores from where his father hails. Located on the highlands of the Manggarai Regency, the town lies within a central coffee farming region on the island. As a child, Hamboer recalled his father always bringing dark-roasted ground Flores coffee back to Jakarta as gifts.

As an adult, while knee-deep in a stressful stint as a corporate lawyer, Hamboer became more curious about coffee production in Manggarai. He eventually quit his law firm in 2014 and shifted gear to coffee processing.

Starting out, Hamboer faced an immediate problem in Manggarai: the ubiquity of intermediaries [tengkulak] dominating the coffee market. They’d often lowball farmers through an exploitative rural credit system [ijon]. Ijon essentially provides loans to farmers paid for by their future crops at a low price.

“When I asked how much the coffee cherries were selling for,” Hamboer says, “I said, ‘are you serious—how could it be that cheap?’” When asked how much cherries were sold for in 2014, Hamboer replies: “Rp. 2,000/liter [US$0.13/liter].” Instead of by weight, cherries in Manggarai are usually sold by volume.

“So I tried to set up something fair to the farmers. They’re the ones doing the planting; they’re the ones nursing [the plants]. If they’re not happy financially, I wouldn’t feel good.” Luckily, cherries are fetching much better prices nowadays (about Rp.10,000/liter).

Intermediaries are baked into every step of travel in the region—in villages, on roads to bigger towns—taking a share of coffee profits along the way. Their methods are enabled by how difficult it is to travel from a coffee farm in the region to a washing station or larger town like Ruteng. For comparison, it takes Mayasari thirty minutes to get to the farms from her washing station, and sixty to ninety minutes from her warehouse in West Bandung. In Manggarai, it can take Hamboer three to six hours to get to farms from his washing station in Ruteng.

Due to these logistical challenges, farmers have trouble finding direct buyers—which is where intermediaries come in. “Access to buyers is what [the farmers] don’t have,” Hamboer points out. “For transportation, they could rent a share taxi [angkot—short for ‘angkutan kota’/‘city transport’] or a truck. But they don’t know who they can sell to. Even the people who stand guard in front of the shops in Ruteng are themselves intermediaries. So the ijon system is already very entrenched there.”

The solution, for Hamboer, was to establish his own farmers’ group [kelompok tani] for Tuang. He began with 40 farmers from a village called Biting, a 3.5-hour drive from Ruteng. Working with his own farmers’ group allowed Hamboer to buy cherries directly and provide suggestions to farmers on how to boost crop quality and consistency.

While quality and yield have greatly improved for Tuang, there are still obstacles, like the general decline in crop production and unstable price swings. Besides heavy rainfall, farmers encountered an insidious form of price manipulation this year.

Hamboer explains that the situation stems from the high prices cherries fetched this year: “Many people ‘promised’ farmers to purchase [cherries] at a high price. But they end up only purchasing one bag, which can consist of 50 or 60 liters of cherries. The farmers, of course, hope that the remaining cherries will be bought at the same price—let’s say a farmer could harvest ten bags of cherries. But in the end, only one bag is purchased, the rest sits and rots in storage. So there are definitely parties who are gaming the system.”

The promise of a high purchase price—sometimes as high as Rp.17,000/liter [US$1.13/liter]—would prevent many smaller companies/ processors from being able to afford the cherries. Farmers, moreover, would hold on to the cherries rather than sell them to other parties, only to be left hanging with rotting crops that cannot be sold to anyone else.

This year’s inflated cherry price could drive away small companies/processors from Manggarai come next harvest season. After decreasing competition, the few remaining larger companies could then resume lowballing farmers by lowering cherry prices again.

For Hamboer, focusing on specialty is one way to get around the high cherry prices: “Since we work directly with farmers, we cut through the [supply] chain quite a lot. So we’re confident in paying however much the asking price is, as long as it’s still reasonable and not suddenly skyrocketing. If we calculate the cherry prices [and consider processing the coffees] for export or hyper-specialty market, and the margins look okay, we will buy [the cherries from the farmers].”

As I was flying back to Chicago, ready to step back into the everyday rhythm of operating my roastery, I reflected on just how much encouraging change I saw. My hometown Jakarta is a cacophonous, traffic-filled metropolis. Spending time at the rural, much quieter, coffee farms made me feel reconnected to my birthplace in a different way, complete with cottagecore daydreams.

There’s still so much work to do in Indonesia, and climate change poses a real threat to coffee growing there. It feels more urgent than ever to support smaller processors like Klasik, Java Halu, and Tuang, who are on the ground year-round dealing with the reality of a warming planet.