A new coffee sensory tool just dropped—and it doesn’t speak arabica.

Launched in May 2025, the Canephora Flavor Wheel is the first open-access lexicon developed exclusively for Coffea canephora, the coffee species commercially known as robusta.

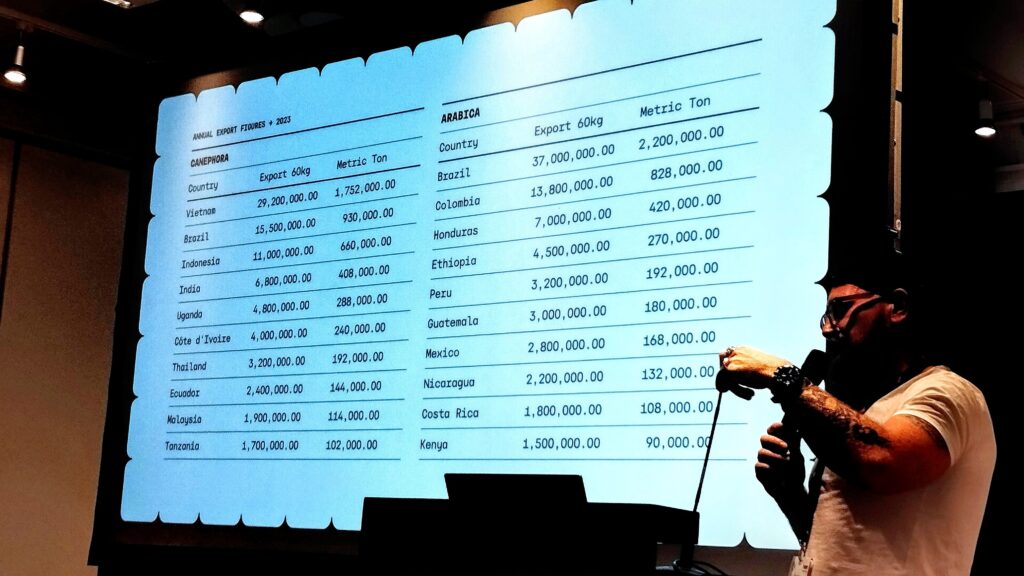

According to the International Coffee Organization, robusta accounts for approximately 40–45% of global coffee production. The top six producing countries by volume—Vietnam, Brazil, Indonesia, Uganda, India, and Côte d’Ivoire—collectively supply about 95% of the world’s robusta. But unlike arabica, which has been cultivated and studied for centuries (with records dating back to 15th-century Yemen), robusta entered global trade only in the late 19th century.

Compared to arabica, robusta is known for its higher caffeine content, faster growth cycle, and greater yield. Those qualities made it ideal for industrial supply chains, especially as post-war urbanization and demand for accessible caffeine grew across Europe, North America, and parts of Asia.

These factors led to robusta’s use in espresso blends and in the production of instant coffee. Still, despite its ubiquity, robusta has long been understudied and undervalued by the global coffee industry.

Now, this new canephora flavor tool might finally change that.

A Complicated Relationship

For decades, “specialty coffee” has been primarily associated with arabica. In 2003, the Coffee Quality Institute (CQI) introduced the Q Grading System, establishing standardized sensory protocols that aligned with the Specialty Coffee Association’s (SCA) definition of specialty coffee. In effect, those protocols dealt exclusively with arabica.

Robusta, in contrast, was left out of this framework. That changed in 2010, when CQI, together with Uganda’s Coffee Development Authority, introduced the “Fine Robusta’” protocols. The launch of the R Grader certification marked another turning point, creating a pathway for quality-focused production and the formal recognition of robusta’s potential.

But robusta still lacked its own lexicon, despite its distinct biochemistry. Compared to arabica, it has more caffeine, different sugar profiles, and higher chlorogenic acids, which can contribute astringent, bitter, or sour flavors.

In 2015, the SCA updated its Coffee Taster’s Flavor Wheel based on research using 105 coffee samples, 45 of which included robusta or blends. However, the robusta samples were commodity-grade, typically used in supermarket blends and instant coffee. As a result, the descriptors reflected its lowest commercial expression, not its full sensory potential.

While the CQI’s R Grading protocol provided a structure for quality assessment of robusta, the new Canephora Flavor Wheel marks a major step forward. By supplying missing descriptive language, it more accurately captures the full spectrum of robusta’s flavors and attributes.

The Wheel in the Making

Lucas Venturim, a coffee producer from Espírito Santo, Brazil, has been working on canephora quality development since the early 2010s. He sees the arrival of the new flavor wheel as part of a much-needed evolution for the coffee species.

“Even with CQI protocols in place, positioning high-quality robusta in the specialty market has been a hard-won journey,” Venturim says.

Previously, many people didn’t have reference points for robusta’s characteristics, he says. “We’d send samples [to buyers], and they’d often be judged using arabica standards. Now, there’s a calibrated vocabulary. Roasters can identify desirable notes, and we can finally communicate our coffees. That was the missing link.”

Brazil accounts for about 40% of all robusta produced, and the country’s specialty coffee association, the BSCA, has been especially welcoming to robusta growers. In 2018, the BSCA introduced a dedicated category in the Cup of Excellence, marking a milestone that recognized quality-focused efforts by producers and scientists. These advancements have been bolstered by long-standing government support, building on Brazil’s established arabica research infrastructure.

That context helps explain why the Canephora Flavor Wheel—developed by a multidisciplinary team with expertise in sensory science, neurobiology, agronomy, and field research—originated in Brazil.

The wheel was developed by Dr. Fabiana Carvalho—a neuroscientist with a PhD in psychobiology and founder of The Coffee Sensorium, a scientific and educational company—who led the conceptual framework and research behind the project. She was joined by Dr. Lucas Louzada, COO of Mió coffee farm and a former researcher at the Federal Institute of Espírito Santo. Dr. Enrique Alves, a senior geneticist at Brazil’s agricultural research agency, additionally contributed, bringing expertise from more than a decade of field research conducted in the Amazon.

The project also counted on the support of researchers Alvaro L. L. Cassago and Mateus M. Artêncio, alongside PhD students, roasters, and traders who volunteered to collect data and gather samples.

The Canephora Flavor Wheel project has quickly expanded beyond Brazil. The wheel was developed using samples from 13 countries, including Peru, Ghana, Mexico, Vietnam, Indonesia, Kenya, and Uganda. Cuppings in Europe took place in Switzerland, with institutional support from the Coffee Excellence Center at Zurich University of Applied Sciences.

“The wheel is a global contribution—an answer to a global need,” says Alves. He believes that for Coffea canephora producers worldwide, the wheel offers a way to tell their stories—and those of their coffees—on their own terms. “It’s also a tool to reframe identity and value,” he adds.

The project took five years to complete and was born not from a funding initiative, but from a shared sense of urgency to develop language around robusta. “There was no contract, no ego—just a desire to build something needed,” says Louzada.

The wheel, along with the methodologies used to design it, was published in “Scientific Reports” on May 13. Carvalho started a GoFundMe in January to keep findings open-access.

The End of Comparison

Researchers identified a wide range of positive sensory attributes present in high-quality robusta coffees. Among the 103 descriptors added to the wheel are coconut water, tomato, toasted cashew, umami, soy sauce, rosemary, and black tea.

This flavor diversity was consistent across international cupping panels—from origin producers to roasters and cuppers in global markets—demonstrating that robusta quality can indeed be described through a shared sensory language.

“We want people to understand Coffea canephora clearly, consistently, and scientifically,” says Louzada. He notes that this is only the beginning: The current wheel is just the first version, and ongoing research will continue incorporating new origins and countries.

For roasters like Nick Mabey of Assembly Coffee in the United Kingdom, the wheel is more than a scientific tool—it’s a shift in mindset. “We’ve been cupping outstanding robustas for years,” he says. “But we had to describe them using arabica’s language.”

“The species has always intrigued me from a contrarian point of view,” Mabey adds. “I suspected there was untapped potential—both sensorially and historically.” He contributed both feedback and cupping samples during the wheel’s development.

At World of Coffee 2024, Dr. Carvalho co-hosted a panel about canephora with Mabey. During her closing remarks, Carvalho likened arabica and robusta to red and white wine.

“They’re both wine—but they have their own flavor profiles, their own wheels, and their own place at the table. No one drinks white wine expecting it to taste like red. And no one calls white wine inferior for not being red,” Carvalho said. “It’s really that simple. This is a coffee species whose cherries produce a coffee beverage. And there are markets that appreciate that.”